Jakarta may be the political capital of Indonesia, but it is certainly not the capital of Indonesia’s art scene. At least not when it comes to the production of art; for that you go to the cities of Bandung and Yogyakarta, which have the feel of leisurely university towns. Densely populated and unhealthily congested, Jakarta is a teeming megacity housing roughly ten million people in its centre (over 30 million if you take in its outer zones), and a no-nonsense commercial hub dating back to its earliest known roots as a seventh-century port city. So naturally the city is home to two art fairs – Art Jakarta, set up in 2009 and previously known as Bazaar Art Jakarta, and the newer Art Stage Jakarta, set up in 2016 as the offshoot of a Singapore fair – as well as a network of commercial galleries catering to a collector base formed of the country’s metropolitan elite.

In November last year, however, two major events marked what might be a coming-of-age for the city’s art scene. The first was the opening of the privately funded 2,000sqm Museum MACAN, which is billed as the country’s first purpose-built contemporary art museum: a milestone institution in a country with an impoverished public art infrastructure. The space, located on the fifth floor of a mixed-use development in West Jakarta, comprises a gallery, offices, a conservation lab and storage areas. The inaugural exhibition is drawn from the private collection of its owner, Haryanto Adikoesoemo, president director of the AKR Group, comprising PT AKR Corporindo Tbk, a chemical and energy logistics company, and the luxury property developer AKR Land Development. In 2016 he was ranked the 20th most wealthy man in Indonesia by the Jakarta Globe, with an estimated net worth of US$1.7 billion. Following its inaugural show, the museum plans to stage exhibitions on midcareer Indonesian artists as well as to host international touring shows.

The second significant event was the 17th edition of the Jakarta Biennale, a low-budget, high-concept six-week showcase. Featuring just over 50 Indonesian and international artists, the exhibition took the theme of jiwa, a hard-to-translate Indonesian word roughly meaning soul, spirit or, as its artistic director Melati Suryodarmo tells ArtReview Asia, “the energy that moves us, moves our life, that connects us to other beings and substances”. With a budget of US$450,000, the event took place across four venues, the main site being a warehouse complex called Gudang Sarinah Ekosistem in the city’s south. Staffed by an army of volunteers and occasionally on the verge of chaos, with some installations not ready on the opening day, it had a sense of energy helped by dynamic curation and international buzz from the participation of top-drawer contemporary artists such as Luc Tuymans and Hito Steyerl.

MACAN and the Jakarta Biennale may be very different in character – the former slick and well oiled, the latter grungy and DIY – but both share a belief in improving public access to art in a city where state-funded cultural institutions are lacking

Both these events are very different in character – MACAN slick and well oiled, the biennale grungy and DIY – but they share a belief in improving public access to art in a city in which state-funded cultural institutions are lacking. The only major government-run art museum in Jakarta is the National Gallery of Indonesia, which houses the national collection, but its facilities, curatorial rigour and exhibition design fall below the professional standards of most national museums.

Private museums already play a big part in the cultural landscape of the city, but none of them are on the scale of MACAN or share its ambitions in programming. Instead many are open by appointment only or require an introduction for access. Those that are open to the public are generally static and do not offer a changing exhibition schedule that promotes both local and international art. These include the Akili Museum of Art, which houses the collection of the family of Rudy Akili, owner of Smailing Tour, one of Indonesia’s largest travel agencies, and the Ciputra Museum, opened in 2014 by property developer Ir. Ciputra as part of a swanky multipurpose development in downtown Jakarta.

Crucially, MACAN’s conservation facilities allow the institution to take loans from overseas and to show travelling exhibitions – which has been a difficulty for Indonesia because so few of its arts centres have the right climate controls in place. Accordingly, MACAN’s director, Aaron Seeto, previously curatorial manager of Asian and Pacific Art at Queensland Art Gallery in Australia, envisions that the opening of his institution “shifts what audiences in Indonesia can see”.

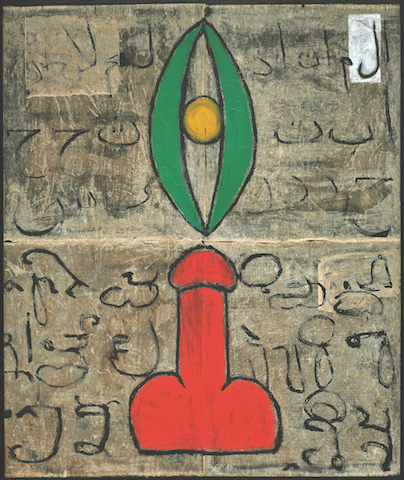

Its inaugural survey, Art Turns. World Turns, gives a taste of the museum’s curatorial standards and the nature of the private collection. Put together by Charles Esche, director of the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven (and curator of the 2015 Jakarta Biennale), and local curator Agung Hujatnika , the 90-or-so works on show trace the intersecting spheres of art history and world history, with a focus on Indonesia. The Indonesian modern section opens with colonial-era art, with works by masters such as Raden Saleh, who painted in the Western tradition during the Dutch colonial period in the nineteenth century. The exhibition then flows through to the country’s anticolonial and independence movement during the 1940s and early 50s, represented by classical revolutionary works by S. Sudjojono and Dullah, and later, the formal experimentations of Hendra Gunawan and Affandi. As the show moves towards the contemporary, however, the story, and more particularly Indonesia’s place within it, fizzles out with a loose international showcase that is heavy on works by blue-chip internationals. There is a Mark Rothko, a Jean-Michel Basquiat, a Gerhard Richter, two Andy Warhols, a small room for Damien Hirst; and from Asia, Yoshitomo Nara, Lee Ufan, Ai Wei Wei and Liu Ye. There is a smattering of politically challenging works. These include Arahmaiani Feisal’s Lingga-Yoni (1994), a painting depicting Hindu iconography of male and female genitalia laid over Arabic script, which provoked censure from Muslim hardliners and forced the artist to flee the country, and FX Harsono’s painting Wipe Out #1 (2011), addressing the erasure of ethnic-Chinese minority identity in Indonesia.

Private philanthropy is especially important in Indonesia, which, globally, is sixth from bottom in terms of economic equality

MACAN has been generally well received by the local arts community. Private philanthropy is especially important in Indonesia, which, globally, is sixth from bottom in terms of economic equality, according to a 2017 report from Oxfam Indonesia and the International NGO Forum on Indonesian Development . The wealth of the four richest people in Indonesia is equal to the wealth of the country’s poorest 100 million citizens. One of MACAN’s stated priorities, which mimics that of a publicly funded museum, is education.

Also championing a more egalitarian, community-focused way of experiencing art is the Jakarta Biennale. Having come a long way since its inception in 1974 as a stuffy, painting-oriented exhibition, it has developed into a key grassroots event. Its recent resurgence has a lot to do with the appointment of influential Jakarta-based artist-curator-impresario Ade Darmawan as artistic director in 2009. Upon his return from a two-year residency at the Rijksakademie Van Beeldende Kunsten in 2000, he and some friends set up the artist collective Ruangrupa (meaning ‘visual space’) in Jakarta. Darmawan describes the group as an “arts centre without a building”, and it is now the most important cultural entity in the city, organising exhibitions and workshops, and publishing books. In keeping with that, under his stewardship, the Jakarta Biennale became less constricted by the fine-art paradigm and more directly engaged with the urban environment. The main venue for 2013’s Siasat (meaning ‘tactics’) was an underground car park, for example, and other art projects included installing a futsal court beneath the highways in the crowded Penjaringan area of North Jakarta. Last year, he remained executive director of the event, overseeing fundraising and project and event management.

In curatorial terms, the current biennale is lively and layered, with several discernible points of enquiry around the concept of ‘soul’. Obviously the jiwa theme encompasses the kinds of knowledge outside rational thought, with artists looking to nature, the body and animistic traditions for inspiration. Connecting spirituality and nature is I Made Djirna’s dramatic work made up of thousands of volcanic rocks (Unsung Heroes, 2017), which he scavenged from a Balinese beach and carved into faces. The cavernous installation has a visceral impact. On one hand, it evokes mysticism and worship, with the rocks arranged in heaps on the ground like religious offerings, or hammered onto the walls like altarpieces; on the other hand, it has echoes of other awe-inspiring organic forms: the ropes of rock dangling from the ceiling form thick curtains reminiscent of the aerial roots of banyan trees. Rooted in another type of prereflective, bodily awareness is Chiharu Shiota’s video in which she douses herself in a bathtub with mud over and over (Bathroom, 1999). The dirt and the bathroom setting invite comparisons with excrement, and notions of fouling and purification are suspended in ambiguity as she embraces the corporeal and the earthly.

There was also a reparative interest in addressing missing histories, both in the context of Indonesian art history and in terms of a wider social and political narrative. To this end, a special showcase of four radical Indonesian artists, all born during the 1950s but whose work has remained in varying degrees of obscurity, was staged, highlighting both their artworks and archival materials related to their practice. They are sculptor Dolorosa Sinaga, the ceramic artist Hendrawan Riyanto, avant-garde musician I Wayan Sadra and artist-activist Semsar Siahaan. Meanwhile, other artists tackled other aspects of historical amnesia and personal memory. For example, Arin Rungjang’s seven-channel installation Bengawan Solo (2017), which shows musicians performing the eponymous folksong in the languid keroncong style, features intertwining narratives surrounding the tune. One story is about the artist’s sexual awakening, referencing Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love (2000), on which soundtrack Bengawan Solo featured. Another is an interview with the Indonesian-Dutch singer Anneke Gronlöh, who performed one of the most popular renditions of the song. The last narrative is an investigation into the river Bengawan in Solo, on which the song is based. It is a place where bodies of Chinese people and communists were dumped during a period of ethnic and political violence from 1965 to 1966.

Curatorial agility aside, the most recent biennale had another populist achievement: securing a presence in the historic Fatahillah Square at the heart of colonial Batavia and a key destination for tourists and Indonesian out-of-towners on the weekends. Overlooking those crowds were Sinaga’s ten lifesize statues of Sukarno, Indonesia’s first president, which were placed at one of the grandest colonial-era buildings in the area, the Jakarta History Museum. The expressive sculptures, one with arms flung to the air, another with fists clenched, stood in frozen oratorical poses on an elevated platform. Even in the hectic, noisy environment, the Sukarnos made an impression. When I was there, some teenagers bypassed the ticket booth at the museum’s entrance, scrambled up onto the platform, flung their arms around the statues and took selfies. The guards allowed a few snaps, and then shooed them away.

From the Spring 2018 issue of ArtReview Asia