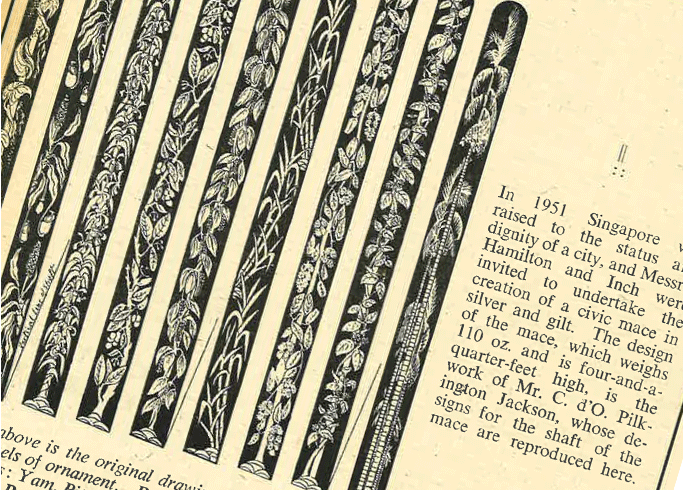

In 1953 Art News and Review – as ArtReview was then styled – celebrated the recently completed production of a ceremonial mace for Singapore City Council by publishing the designs, by the Scottish sculptor Charles d’Orville Pilkington Jackson, for the decoration of its shaft. ArtReview’s erstwhile, anonymous and presumably deceased colleagues note that the nine facets of the mace were covered with depictions of typically Malayan flora, including orchids, rambutans, peppers and betel nuts, and that it was fabricated by Hamilton & Inches, an Edinburgh-based silversmith.

The silver and gilt mace, sponsored to the tune of $15,000 by local philanthropist Loke Wan Tho, was commissioned to mark the Royal Charter issued by George VI that had elevated Singapore to city status two years previously. The botanical motifs on the mace’s shaft were suggested by a committee in Singapore comprising Loke, university professors and the staff of Raffles Museum, which later became the National Museum of Singapore.

Although the story of the mace became more turbulent – and thus perhaps more newsworthy – as time went on, the magazine didn’t follow up. Until now.

At a ceremony in April 1954 Loke presented the mace to T.P.F. McNeice, the president of what was now established as a city council. McNeice (who was Loke’s brother-in-law), a sombre individual with a taste for double-breasted suits, took possession of the almost-two-metre-long staff; a photo shows that he was watched over by a portrait of the newly crowned Queen Elizabeth II. He hoped, The Straits Times reported, that the treasure would come to symbolise the authority of the council and ‘inspire that enthusiasm and loyalty which is the most essential ingredient to the well-being of any city’. Loke agreed that the mace ‘is a signpost in our recorded history pointing, I hope, to a greater and nobler Singapore’.

A greater and nobler Singapore was indeed on its way: Ong Eng Guan, an anti communist, anti-British, Chinese-educated politician and founding member (and treasurer) of the People’s Action Party (which won a landslide election in 1959 and remains Singapore’s governing party today) was beginning to draw attention with his denunciations of colonial rule. On 21 December 1957, following the first city council elections (after Britain had agreed to Singapore’s self-rule), Ong was elected mayor. Following his arrest (after a scuffle over firecrackers and the appropriateness of their use on such occasions) during an aborted inauguration ceremony on 23 December, a large rambunctious public (strategically packed with PAP supporters) turned out to see his official elevation to the post the following day. They booed loudly when Lee Bah Chee congratulated Ong in English alone. Speaking in Malay, Chinese and English, Ong declared that he would serve ‘those sections [of society] which have been neglected for so long in the past’. From commitments to sewage systems and housing, he moved on to the matter of the mace that stood before him, declaring

it ‘a relic of colonialism’ and calling for a motion declaring that it ‘be hereby disposed of’. Excluding abstentions, the council backed the proposed action unanimously, to great applause from the public galleries. ‘We are living in a revolutionary Asia,’ Ong said, ‘and we, the people of Singapore, are part of the Asian revolution. We do not want to follow the centuries-old tradition of the British mayors. We do not want to live or dress differently from our people. We do not want to see the chains of colonialism and the mantle of despotism worn by representatives on this city council.’ The British conservative MP Sir John Barlow, then visiting Singapore, offered to buy the mace as a souvenir of colonialism. His father, also called John, had made the family fortune (via offices in Calcutta, Shanghai, Singapore and Kuala Lumpur) trading the kind of crops depicted on the mace.

After a brief, tumultuous merger with Malaya, Singapore became independent in 1965.

Having disposed of his mayoral robes and mayoral residence, Ong went on to reject a request for special lighting for a visit to Singapore by Prince Philip in 1959. He later lost a PAP election to decide who should be Singapore’s first prime minister by one vote to Lee Kuan Yew. One year later he was expelled from the PAP. He retired from public life in 1965, and in 2012 it was reported that he had died in 2008.

Ironically, Pilkington Jackson’s best-known works commemorate icons of Scottish nationalism, chief among them his equestrian statue of Robert the Bruce, installed at Bannockburn in 1964 to mark the 650th anniversary of victory of the King of the Scots over the English.

The mace itself escaped destruction and now sits in the collection of the National Museum of Singapore.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2019 issue of ArtReview Asia