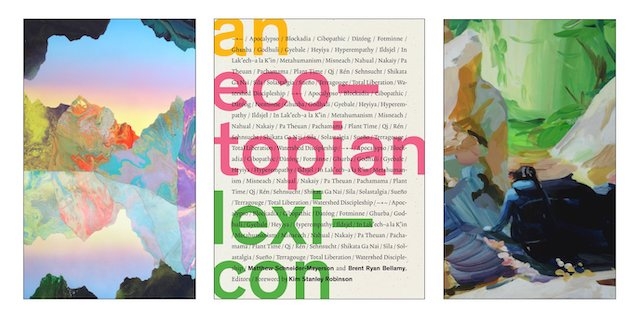

Edited by Matthew Schneider-Mayerson and Brent Ryan Bellamy, University of Minnesota Press, $24.95 (softcover)

Reviewed by Adeline Chia

Like microplastics, mentions of the Anthropocene have been everywhere for a while now. From articles about climate change to scholarly essays on psychotherapy (‘ecological grief’, anyone?), the current geological epoch named after humankind’s impact on earth is inescapable (even if you don’t believe in it). Needless to say, it doesn’t make for cheerful reading. The tenor of most environmental coverage is apocalyptic. The List of Doom includes: rising sea levels, ocean acidification, desertification, The Sixth Extinction and whatever sign of how human beings – or, to be more historically accurate, Western industrialist nations (well, mainly) – have screwed up the planet.

Which is why this book, a lexicon of new words via which to address climate change, is such a breath of fresh air. Comprising concepts from sci-fi and loanwords from other languages, the index doesn’t downplay the direness of the ongoing environmental disaster but does give us new perspectives from which to respond to it. Each entry features the loanword and an essay explaining its provenance and application. The texts, which are written mostly by professorial types whose specialties include English literature, anthropology and environmental studies, range from the drearily academic to the gloriously weird. But the entries’ basic messages are: do not despair; be humble; get creative.

Some words are direct calls to action, such as blockadia (popularised by Naomi Klein’s 2014 This Changes Everything), referring to unconventional efforts by different interest groups – including indigenous ones – to oppose extractive industries. Others are more philosophical, advocating a loosening of the boundaries of the self to be more attuned to nonhuman others (pa theuan, from the Thai, meaning ‘wild forest’ and referring to spirits, gods and wild animals, a class of unpredictable beings that cannot be known but must be respected), or being open to the wider flow of life through all creation (sila, from Inuit, meaning the interconnectedness of all phenomena, reminiscent of the Tao or the Force in Star Wars). And then there is the kooky corner. ~*~, a loanword from dolphinese, is pronounced by ‘lightly blowing a stream of air across the sensitive back of one’s hand’, writes Melody Jue. The official meaning is ‘tickling at a distance’, and can apparently be used to communicate ‘ecological affects’ such as ‘the vibrations of an earthquake, the force of a tsunami, or the rush of monsoon wind’.

Crunchy? Maybe a little. But then again, where did the stone-cold rationality of Western Enlightenment get us? Colonialism, misogyny, senseless ecological plunder leading to the apocalypse, etc. In these end times, there is a case for opening your mind to radical alterities. In fact, the most powerful words in this glossary are those that act on us not just by rational argument but other more mysterious, invocative ways. Take misneach, from the Irish, meaning a type of courage for those not in the mood to be courageous. Its pronunciation, mish-nyuhkh, fleshy and wet, mobilises the entire mouth as well as the imagination. It is a one-word poem. Then there’s fotminne, or ‘foot memory’, from Swedish novelist Kerstin Ekman’s Blackwater (1993), meaning our primeval connections to the ground beneath our feet, a poetic way to think about our relationship to land as one of embodied memory. You don’t remember a place, your feet do. Another evocative word is godhuli, from the Bengali, ‘the time of day when cows, with their hooves kicking up dust, return from pasture to their nightly refuge’. (Or twilight in boring old English.) A beautiful, prismatic word that combines illumination and dirt, it is also an auspicious time for Hindus to conduct ceremonies such as weddings.

Writing about a work by artist Alex Hartley called Nowhereisland (2012), where a piece of land revealed by Arctic glacier melt is towed around the coast of England, American artist-activist Suzanne Lacy quotes Ference Marton, Ulla Runesson and Amy Tsui in Classroom Discourse and the Space of Learning (2004): ‘Powerful ways of acting spring from powerful ways of seeing’. It seems counterintuitive to think of the Anthropocene, this godhuli hour on earth, as a blessed time. But the climate emergency has inspired collective action, imaginative art and expanded worldviews. We might be richer for the experience – provided we come out the other side.

From the Spring 2020 issue of ArtReview Asia