Green Art Gallery, Dubai, 13 March – 6 May

There’s a funny, lukewarm stillness to this show, like looking at your feet in a fast-cooling bath. It’s hushed without feeling sacralised, and tepid in an earnest kind of way: a small, shy smile of a show that beguiles even as it frustrates. But when you approach the kinetic sculpture Chanting if I live, Forgetting it I die (2017), a centipede of stained marble and weathered wood, something shifts. Sensing your presence, the tergitelike marble slabs begin to wave at random: slowly, and with some drag, like an underwater anemone. The sculpture begins to breathe. And all of the surrounding works seem to sigh in relieved accord, as if they hadn’t realised they had been holding their breaths. Hera Büyüktaşçıyan often seems as comfortable in the diverse roles of oral historian and hydraulic engineer as that of artist, with a poetic approach that excavates the history of a site as a starting point. Her works come to function as receptacles that coax repressed narratives – traumas, tales, such as the Armenian Genocide and Istanbul Pogrom, of violent erasure, or simply the stories that time forgot – back into the present to flow like the water that is so central to her practice.

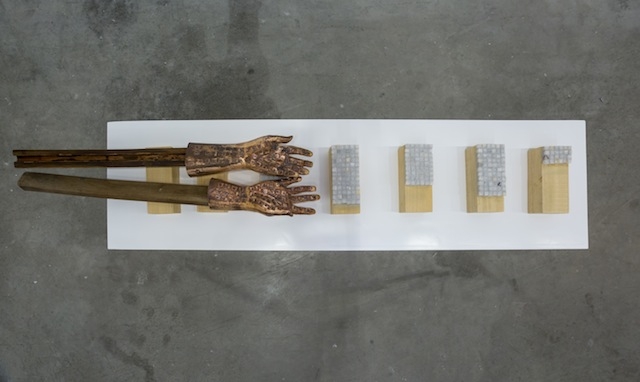

In her first Dubai solo exhibition, the artist extends her preoccupation with aquatic infrastructure to consider marbleworking, as well as the labour camps not far away. The invisible, uncited labour of workers buttresses the exhibition, most winningly in The Relic (2016), a pair of cast bronze hands extended in supplication over a series of neat marble mosaics on wood. Deeply stamped squares on each finger suggest a transubstantiation of flesh into marble, as if the tiles have been cut from the worker’s hands. One of the strongest works in the show, it pays quiet homage to all those whose identities have been eroded over centuries of building, be it the grand marbled monuments depicted elsewhere in the show or Dubai’s nearby skyscrapers. On a nearby wall, titled A Discovery of 36 Wells (2016), a suite of pencil and watercolour drawings depict workers’ homes in Dubai. The buildings have been upended and placed on their sides to become broken cisterns and leaky aqueducts. But the liquid that pools below these structures is a pinkish red, suggesting a diluted admixture of water and blood. Less successful is Everflowing Pool of Nectar (2017), a large installation of chevroned paper scrolls that dominates the gallery space. Within the patterning are images of the fountains and waterways found in Mughal pleasure gardens, scenes of recognisably Byzantine men at work, perhaps a comment on the transnational character of labour. In his multivolume treatise on architecture, the Roman engineer Vitruvius wrote that marble is not alike in all countries. Except here it is. There’s a flattening subsumption of memory to material, which seems to rehearse the same effacement that the artist seeks to counter. And perhaps it wouldn’t matter in a place where the embedded memory of the site worked, as it does so elegantly in her other works, to suffuse and animate the show. But in Dubai, the water table has long been extinguished and the riverbed remains dry.

From the Summer 2017 issue of ArtReview Asia