In Search of Southeast Asia through the M+ Collections at M+ Pavilion, Hong Kong, through 30 September

Until its opening proper, exhibitions staged by Hong Kong’s not-quite-actually-existing megamuseum, M+ (construction of which is expected to be completed sometime in 2019, with the museum opening a year later, althoughweveheardsimilarpromisesbeforesoletsassumethatnoonesmakinganyfirmpromises), take place in a pavilion in West Kowloon. Once M+ opens, its pavilion will ‘become a new space for artists, designers and organisations to stage independent small-scale exhibitions and events’, which tells you both how modest the pavilion is when compared to the Herzog & de Meuron-designed museum building and that someone at M+ seriously believes that something old can become something new. Of course, making old ideas seem new is one of the primary functions of the museum today. This month sees the opening of the seemingly permanently-foetal institution’s first exhibition framed by a geographic focus. Nevertheless, as the title – In Search of Southeast Asia – suggests, curators Pauline J. Yao and Shirley Surya (who represent M+’s departments of visual art, and design and architecture respectively) are operating on the principle that the map is not the territory. Presumably because this geography (traditionally those lands south of China and east of India) is as much an economic and political construction as is it is a cartographic one; and because identifying a subject and then losing (or in curatorspeak, ‘complicating’) it is also what people expect museums to do these days. Articulating this landscape of confusion will be works by artists such as Simryn Gill, Charles Lim, Maria Taniguchi and The Propeller Group, alongside the output of architecture stars of the distant past, such as Geoffrey Bawa, the recent past, such as Ken Yeang, and the immediate present, such as Vo Trong Nghia Architects. Given that Southeast Asia, a term that developed (into whatever we do or don’t know it to mean now) around 50 years ago (partly through the establishment of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in 1967), covers a range of radically dissimilar cultures and languages, but describes a region of similar climates, topographies and histories of colonial oppression, you might say that this exhibition marks a tentative step in figuring out how the museum might go on to develop narratives of inter- and pan-Asian discourse in the years to come.

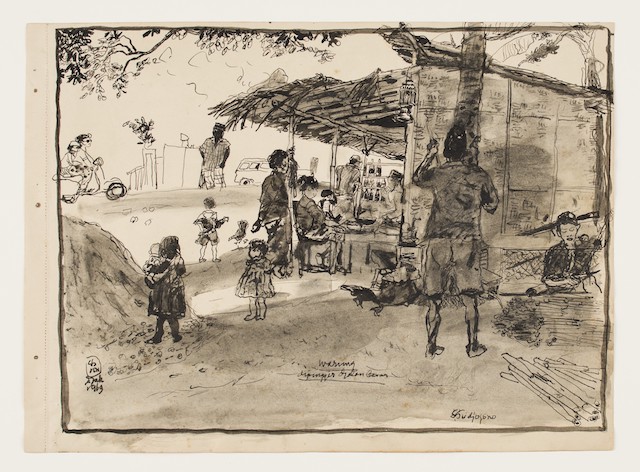

(Re)Collect: The Making of Our Art Collection at National Gallery Singapore, through 19 August

Down in Southeast Asia itself, National Gallery Singapore (NGS), which prides itself on having the world’s largest institutional collection of modern art from the region, is also working out where it is. Albeit by looking at itself. (Re)collect: The Making of our Art Collection examines the journey of collecting and acquiring (both through its own habits and those of the private individuals who have donated works to it) that made the museum, which opened in 2015, what it is today. But this is not simply a tale of how private passions ended up creating a public cultural life. (Although a more cynical writer might see in this show an advertisement for potential donors.) It’s more complicated than that. According to NGS director Eugene Tan, the exhibition offers the gallery an opportunity to continue its task of ‘questioning and re-imagining what constitutes Southeast Asia’. So, other than the fact that whatever Southeast Asia is, it will be at NGS (and here, the elision of the institution’s status as the national gallery for a single southeast Asian country and the biggest institutional collector of art from the region says something about Singapore’s political ambitions), except for the bit that’s in Hong Kong, we’re left with a geography that is again identified only to be lost. In temporal terms the display begins in the postwar period (‘when art took a backseat to nation-building’; btw, performance art was effectively banned in Singapore from 1994 to 2003) through to NGS’s contemporary collections, among which look out for work by Rirkrit Tiravanija, whose offerings also feature in the M+ show. At least there’s something everyone can agree on.

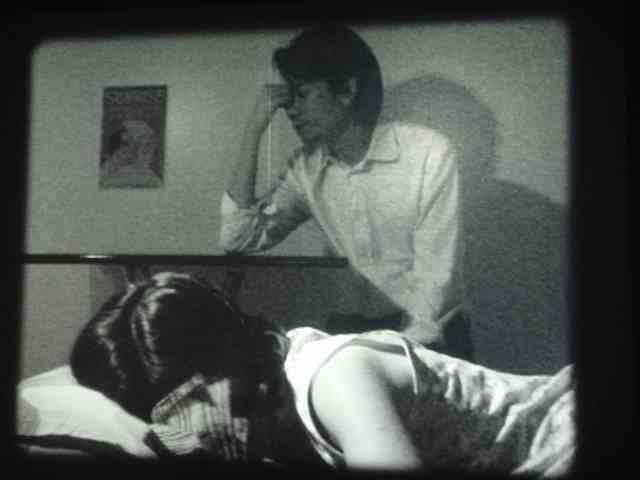

Dismantling the Scaffold at Tai Kwun Contemporary, Hong Kong, through 15 August

Back in Hong Kong, the Tai Kwun Centre for Heritage and the Arts, a US$485 million development of the former Central Police Station designed, like M+, by Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron, which was originally due to open in 2016 until a listed wall collapsed in the heritage part of the building, is finally about to open. Its appropriately named first exhibition, Dismantling the Scaffold, will focus on the work of the now closed local nonprofit Spring Workshop (whose former director Christina Li curates), which during its five-year existence operated a series of residencies and exhibitions mixing local and international talent such as Nadim Abbas, Big Tail Elephant, Leung Chi Wo and Sarah Wong, Marina Abramović, Koki Tanaka and SUPERFLEX. In the spirit of museums using their programmes to justify and identify their own missions and agendas, one presumes that its opening show will locate the expansive gallery spaces of Tai Kwun, which is a partnership between the Hong Kong Jockey Club and the local government without a collection of its own, as a bridge between Hong Kong’s lowkey not-for-profit scene and the megainstitutions that are set to dominate the landscape in the future. Tellingly Tai Kwun will host part of M+’s ongoing talk series M+ Matters.

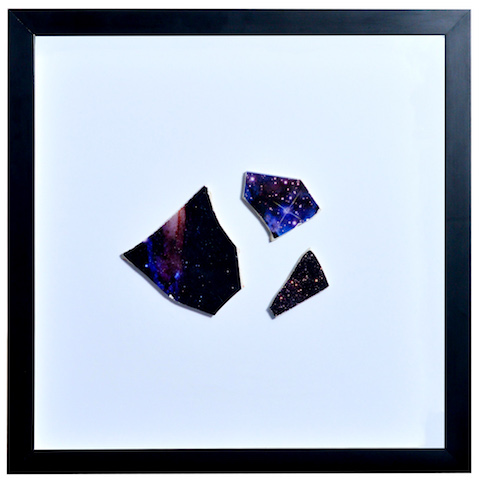

Shared Residence at Ateneo Art Gallery, Quezon City, Manila, ongoing

Diving back down into Southeast Asia (hey, after all that Berlin in Shanghai, London in Shanghai, LA in Shanghai business, it’s starting to feel like a place again, isn’t it?), the Ateneo Art Gallery (part of the Ateneo de Manila University in Quezon City) has an exchange scheme of its own. Shared Residence is an ongoing project, devised by Philippine artist (and Future Greats selector for this issue) Poklong Anading, through which members of the Ateneo community can borrow artworks (donated to the project by their makers) to live with for up to two weeks. The project aims at reformulating collecting as a social rather than personal behaviour pattern, and at relocating art as a part of quotidian living rather than something to be looked at on special occasions. The scheme operates like a library, with fines for late returns and borrowers taking responsibility for the conservation of the work while it is in their care. Sign up to one of Ateneo’s classes and you might take home Anading’s Every water is an island (2013), a 51sq cm video still, or similarly sized works by the likes of Ronald Ventura and Annie Cabigting. It’s like Condo for the people. Or at least for the people studying or working at Ateneo. Let’s hope that Shared Residence spreads as widely and as rapidly as its commercial other.

Second Yinchuan Biennale at MOCA Yinchuan, through 19 September

Those of you who remain unconvinced by all the new models of art distribution, and prefer instead to see things in the big bestial form of a good old biennale, are in luck: June sees the launch of the Second Yinchuan Biennale, directed by Marco Scotini and titled Starting from the Desert, Ecologies on the Edge. Located in northern China, this Muslim-influenced city is the site of multiple massacres, the death of Genghis Khan (in battle) and an irrigation system developed during the Han dynasty in the third century BCE. The biennale takes place at MOCA Yinchuan, which opened in 2015 and whose facade, designed by local practice waa, is articulated in flowing strata designed to reflect the rich geological history of the site – a wetlands area on the edge of the desert. It takes the social, historic and ecological particularities of the site forward through four key binaries – ‘Nomadic Space and Rural Space’; ‘Labor-in-Nature and Nature-in-Labor’; ‘The Voice and the Book’; and ‘Minorities and Multiplicity’ – and through the work of 90 artists. Among this multitude, names to look out for include Congo’s Sammy Baloji, India’s Nikhil Chopra, exiled Iraqi Hiwa K, Singapore’s Ho Rui An, South Korea’s Kimsooja and Vietnam’s Thao-Nguyen Phan, as well as Chinese stalwarts Song Dong and Xu Bing. Of course, relations between place, race and identity will be ‘complicated’ by the biennale and, naturally, as an event of the moment, it will be unsparing in its questioning of itself. Its curators are promising, indeed, to explore ‘the limits of the exhibition format, and thus to eventually produce a new eco-model of exhibiting’.

Tenth Liverpool Biennial, various venues, Liverpool, 14 July – 28 October

By contrast to all that, things sound relatively calm in Liverpool, where the city’s art crowd and more particularly curators Kitty Scott (from the Art Gallery of Ontario and Future Greats nominator for this issue) and Sally Tallant (director of the Liverpool Biennial) are gearing up for the Tenth Liverpool Biennial, titled, in another sign of the fad for lost geographies, Beautiful world, where are you? That’s a line liberated (and translated) from an eighteenth-century poem by German heavyweight Friedrich Schiller, later popularised when it was set to music by the Austrian Franz Schubert in 1819, a time of great European upheaval. And upheaval, European and other, is what connects the whole shebang back to Liverpool 2018, where 40 international artists will be plotting out the territory and, one presumes, attempting to answer the question. New York-based performance artist Ei Arakawa will produce a new LED-‘painting’ based on a suite of paintings featuring dancers by fellow exhibitor Silke Otto-Knapp; Ryan Gander is, in turn, collaborating with five schoolchildren from Liverpool’s Knotty Ash Primary School; Ari Benjamin Meyers will create a series of new musical compositions that will in turn become film portraits of some of Liverpool’s native musicians, while artist and theorist Joseph Grigely will present a selection of images from his archive of newspaper images of musicians. Turner Prize-nominee Naeem Mohaiemen will take the focus on collaboration to new places by showing his three-channel video Two Meetings and a Funeral (2017), which traces Cold-War-era politics through the Non-Aligned Movement and the Organization of Islamic Cooperation. Look out also for the work of the late Canadian Inuk artist Annie Pootoogook, whose drawings depicted the realities of everyday life in the community of Kinngait, and Reetu Sattar’s Harano Sur (Lost Tune) (2017–18), a performance work that muses on the place of the harmonium in past and current Bangladeshi culture.

To be continued…

From the Summer 2018 issue of ArtReview Asia