Following on from Part I of ArtReview Asia’s selection of exhibitions to see this summer…

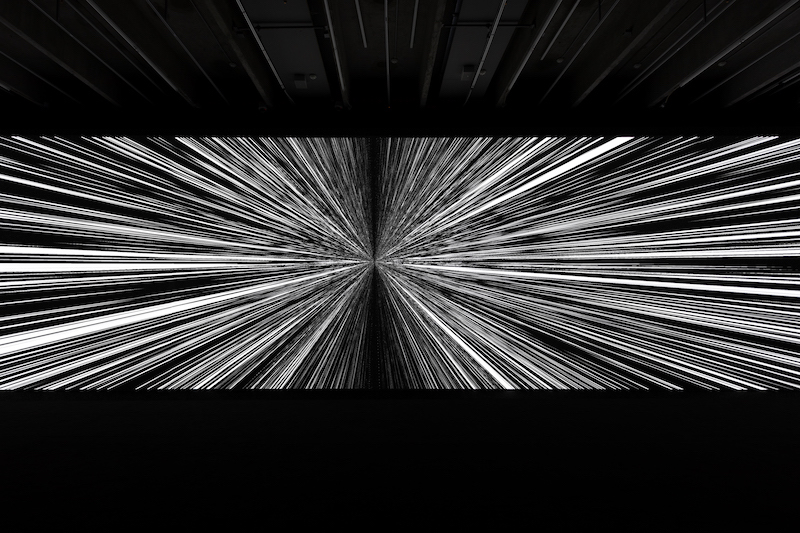

Ryoji Ikeda at Taipei Fine Arts Museum, 10 August – 17 November

Making abstract data sensate has been a part of Japanese electronic music composer and visual artist Ryoji Ikeda’s output (which spans performance and installation, as well as albums and CDs) for well over a decade now. Ikeda uses algorithms to turn data into complex audio and visual patterns that he often deploys in the form of immersive installations. Test Pattern (2008–), for example, converts any information (texts, sounds, photos, movies) fed into it into a series of binary 1s and 0s. These then sequence an audio track that in turn feeds a visual stream of black-and-white barcodes running at hundreds of frames per second. What starts out being a test for the performance of digital devices ends up being a test of human perception itself. Consequently, a number of Ikeda’s installations are best avoided if you suffer from epilepsy, but provide a true immersion into a digital environment. This August, at the Taipei Museum of Fine Arts, the Paris-based artist will develop a new site-specific work.

Tatsuo Miyajima at Minsheng Art Museum, Shanghai, through 18 August

Numbers also play a key role in the work of another Japanese artist, Tatsuo Miyajima, whose current retrospective, Being Coming, at the Shanghai Minsheng Art Museum, presents the work dating from his first use of LED counters as his signature material in 1988. Again inspired by Buddhist philosophy, the counters filter through the numbers 1 to 9, avoiding zeros (the artist has previously said that zero is a Western concept antithetical to concepts of reincarnation), often arranged in fieldlike arrays that respond to each other. Accordingly, Miyajima’s work revolves around three concepts: ‘Keep Changing’, ‘Connect with Everything’ and ‘Continue Forever’. That sounds, to ArtReview Asia, like the fundamental mantra of most contemporary art these days, and perhaps that’s why Miyajima, who, despite the fact that his output now seems so unchanging, trained as a painter and emerged during the 1970s as a performance artist inspired by Joseph Beuys, Allan Kaprow and Christo, before undergoing his personal digital revolution, deserves acknowledgement as being somewhat foundational to the art of today.

Samson Young at Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh, 24 July – 5 October

This July, another musician and visual artist, Hong Kong-based Samson Young, will have his first UK solo exhibition at the Talbot Rice Gallery at the University of Edinburgh as part of the Edinburgh Art Festival. Real Music is being promoted as ‘a provocation to unfix notions of authenticity in music, sculpture and society’ and features the artist’s latest series of installations, Possible Music (2018–), which examine how virtual instruments might sound in unreal environments. A bugle, for example, blown by a dragon whose breath heats up to 300 degrees Celsius. Perfect for anyone suffering from Game of Thrones withdrawal symptoms. A new commission, Possible Music #2 (2019), features a field of speakers creating a 16-channel sound installation, combined with a series of sculptures that create the effect of a colossal trumpet emerging from the earth. Seems like a setup to get someone to use the words ‘ground-breaking’ in relation to that. Not ArtReview Asia of course.

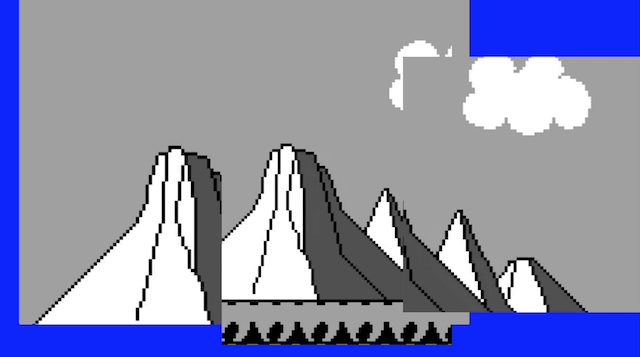

aaajiao at How Art Museum, Shanghai, through July 14

Back from the world of fantasy to the world of the digital (as if there was really any difference) and a solo exhibition of work by aaajiao at the How Art Museum Shanghai. Aaajiao is the pseudonym of Xu Wenkai (it’s ok, this is not an outing, he’s public about that), a Shanghai- and Berlin-based artist who grew up in Xi’an, and who is also active as a blogger and activist, primarily concerned with the social and political impact of the Internet on dailylife. Numbers and data, he postulates, define individual existence, but to an artist born almost 30 years after Miyajima and 20 after Ikeda (in 1984; naturally the content of George Orwell’s famous novel has been a major influence on his work), this is expressed in a form other than the numerical. Instead, aaajiao’s art is expressed via digital prints, sculptural installations and video feeds, many of which consume or spew information (via printouts or video streams) to the viewer standing before them, who is then encouraged to engage with and overcome feelings of alienation engendered by their part in an overwhelmingly connected global technological system. To visualise a problem is to start to overcome a problem, as ArtReview Asia’s therapist is always telling it.

Kohei Nawa at Pace Gallery Hong Kong, 18 July – 29 August

Coming at the relationship between analogue and digital in a different way is Japanese sculptor Kohei Nawa. The artist is best known for his PixCell series of works in which found objects are covered in corallike clusters of transparent spheres so that they appear, to the viewer, as if pixelated, even though, in fact, they are as analogue as it gets. As the individual spheres, according to their size and construction, magnify or distort various areas of the object they encase, collectively they evoke both images of plagues, cancers and mutated cells and the glittering iridescence of a chandelier. New works from the PixCell and drawing series will be shown at Pace Gallery’s Hong Kong space this July.

Cao Fei at Pompidou Centre, Paris, through 26 August

It’s something of a shock to discover that Cao Fei’s solo exhibition at the Centre Pompidou is the first such that the institution has dedicated to a Chinese artist, particularly given the Paris museum’s long engagement with Chinese art, and the fact that the Pompidou is due to launch its new Shanghai outpost in November this year. Still, better late than never, as ArtReview Asia’s publisher keeps telling it. Cao’s exhibition, hx, focuses on a new body of work evolved from research into the neighbourhood, Hong Xia, surrounding her Beijing studio, located in a former community cinema not far from the city’s 798 art district. The area features a number of buildings built during the 1950s with support from the Soviet Union, and was home to many of China’s fledgling electronics industries. Indeed, it was here that the first Chinese-made computer was produced. Now all that’s so much history and the area is scheduled for redevelopment. Cao’s work has always traced the impact of digital cultures on an analogue world, and here the history of Hong Xia will be explored in a new feature-length film, videos, photographs and archival materials. Given the Pompidou’s renewed internationalism, you won’t be surprised to learn that Franco-Sino relations are very much in the air and consequently on the ground at the moment.

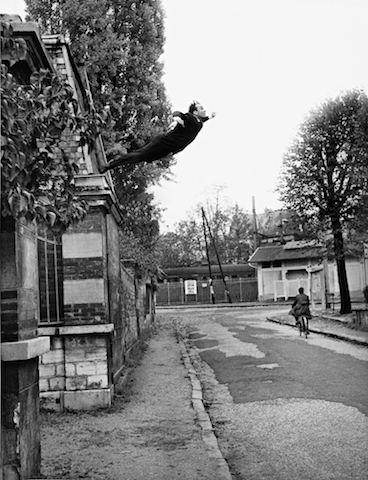

The Challenging Souls at Power Station of Art, Shanghai, through 28 July

Back in Shanghai, at the Power Station of Art, The Challenging Souls presents the work of Yves Klein, Lee Ufan and Ding Yi, tracing a line from the French judo expert and monochromist through to Lee’s involvement with Japan’s Mono-ha movement during the 1960s and Korea’s Dansaekhwa during the 1970s through to Ding Yi’s abstract paintings of the 1980s. The show seeks to o er a comparative appraisal of occidental and oriental avant-gardes of the second part of the last century, and an insight into the performative and metaphysical aspects of painting during that time. Or, to be succinct, it offers a view of three artists whose work is different and the same.

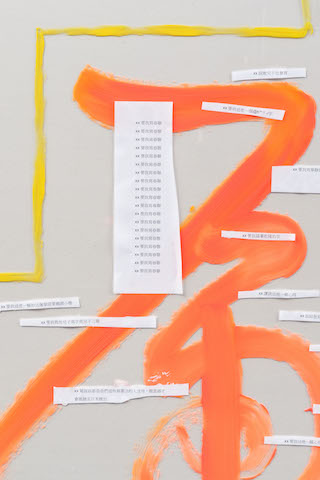

Xu Jiong at Each Modern, Taipei, through 6 July

Equally contradictory on a superficial level is Xu Jiong’s new series of ‘self-portraits without portraits’, now on show at Each Modern in Taipei. Best known for his black- and-white ink works, the Beijing-based painter’s new series takes those calligraphic techniques and applies them to acrylic sheets using coloured paint. The aim is to create a series of self-portraits that explore identity as a historic and social construction. Consequently the acrylic sheets of the new works are laid on top of older works (exploring the artist’s queer identity) and painted with towers (universal symbols of power and control) of various sizes as well as calligraphic renderings of the artist’s name: the result is a multilayered portrait of past and present selves.

From the Summer 2019 issue of ArtReview