ArtReview Asia is going to be kicking off its winter season in Shanghai, so, naturally, that’s where you’re going too. Hey – that’s how it works: ArtReview Asia leads and you follow. Don’t worry though, you’re not being Shanghaied in that sense; there are genuine reasons to visit China’s largest city this November. So ultimately you’ll be going of your own free will. As much as such a thing exists. (At this point you might want to refresh your memory of David Lewis’s 1981 essay ‘Are we free to break the laws?’.)

West Bund Art and Design, West Bund, Shanghai, 8–11 November

Now in its fifth edition, the expanded West Bund Art and Design fair features over 110 international galleries and takes place in over 20,000sqm of exhibition space on the site of Shanghai’s original airfield (and you’ll be reminded at this point that it also provides the setting for J.G. Ballard’s 1984 memoir, Empire of the Sun). Given the amount of space available, the fair has traditionally (as much as the four previous editions constitute a tradition) been a site for more ambitious and experimental presentations than risk-averse commercial galleries might otherwise try to pull off in China. Working with that is ArtReview Asia’s Xiàn Chǎng (you’ll have reached for your New Age Chinese–English Dictionary at this point, and having rifled through it, worked out that xiàn chǎng might variously be translated as ‘the setting’, ‘the stage’, ‘the scene of the crime’, etc) section of the fair, which features solo projects (in the form of sculpture, painting, moving image and installation). This year you can look forward to 14 presentations by Francis Alÿs, Choi Jeong Hwa, Shezad Dawood, Dickon Drury, Sam Falls, Joyce Ho, Liu Jianhua, Tatsuo Miyajima (offsite), Takashi Murakami, Julian Opie, José Patricio, Lawrence Weiner, Cerith Wyn Evans and Zhang Enli.

ART021, Shanghai Exhibition Centre, 9–11 November

While ArtReview Asia takes a minute to think about the implications of determinism in its soft and hard forms, you might also want to visit Shanghai’s other art fair, ART021, which takes place in central Shanghai, in the Shanghai Exhibition Centre, originally constructed (along with its identical Beijing counterpart) as the Sino-Soviet Friendship Building in 1955. There you’ll be able to see some old friends from West Bund (some galleries present at both fairs) as well another hundred or so galleries from around the world. Between the two fairs you might even begin to draw some conclusions as to what’s hot and what’s not in China at the moment.

Shanghai Biennale, Power Station of Art, 10 November – 10 March

But if you’ve been reading ArtReview Asia for a while you won’t be some simple follower of fashion. And that’s why, all art-faired out, you’ll be heading off to the Power Station of Art and this 12th edition of the Shanghai Biennale, curated by Mexican art historian Cuauhtémoc Medina and titled Proregress – Art in the Age of Historical Ambivalence. If that sounds a bit clunky, its guiding metaphor – the concept of yubu, a Daoist dance step in which the performer seems to be going backwards and forwards at the same time – might shed more of a light. Indeed it provides a framework, according to Medina will allow him to ‘explore the role of contemporary art as a means by which the struggles and anxieties of many different latitudes are reflected and turned into subjective experience, training the contemporary subject in the ambivalence the allows us to tolerate the contradictory forces of contemporary life’. Perhaps it will even help you to process the experiences you just had in those art fairs. Look out, at the Power Station, for works by Nadim Abbas, Kader Attia, Yang Fudong and Tomoko Yamada among others.

Taipei Biennial 2018, Taipei Fine Art Museum, 17 November – 10 March

Curated by artist Mali Wu (she’s been described as the ‘godmother’ of Taiwan’s socially engaged art scene) and Francesco Manacorda (he’s the former artistic director of Tate Liverpool and now occupying the same post at the Moscow and Venice-based V-A-C Foundation), this year’s Taipei Biennial is titled Post-Nature – Museum as an Ecosystem. Stealing something natural and making it something cultural is, of course, de rigour in the museum world these days, as you’re about to find out. Naturally, Wu and Manacorda put things somewhat differently when describing the focus of their edition. While there will be mentions of catastrophe, responsibility and the advent of the Anthropocene, for Manacorda the biennial is about art and the infrastructure around it embracing an ecological consciousness rather than describing ecological conditions, something with which Wu (many of whose works involve collaborating with special interest groups and communities), talking to the Asia Art Archive’s Larry Shao back in 2010, appears to concur: ‘Environmentalists are focused in making changes; artists, on the other hand, tell the same story with a different medium, they also give the mind an alternative suggestion – this, I think, is the only difference between the two. I think that environmentalists are more proactive than myself, they invest a lot. I, on the other hand, provide an alternative pathway, platform, as I work towards the same goal.’ What does this mean on an experiential level? Well, at the time of writing the pair are promising an exhibition that goes beyond any ideas of art as a discrete discipline and instead focuses on a holistic approach to the relationship between the natural and the human, along the way embracing the work of NGOs, activists, film and documentary makers, architects and other ‘non-visual artists’. Au Sow-Yee, Futurefarmers, Lucy Davis, Vivian Suter, Jumana Manna, Nicholas Mangan and Robert Zhao Renhui (whose Trying to Remember a Tree (iii) – The world will surely collapse, 2017, a 14-lightbox photographic meditation on the management of nature via an image of a fallen tree, is currently on longterm display in Singapore’s Gillman Barracks), are some of the contributing artists you’ll be familiar with, but as ever, the fun tends to happen when experiencing the work of those with whom you are not. At least that’s what ArtReview Asia is constantly telling itself, otherwise why leave the comforts of home and an array of social media channels?

After Nature, UCCA Dune Art Museum, Aranya Gold Coast, Qinhuangdao, Hebei, through 4 April

Hurray for the great outdoors! And nature, is again the subject (told you so!) at the inaugural show at UCCA’s newest outpost, 270km east of its Beijing headquarters. The venue itself, designed by Beijing-based OPEN Architecture, has connections to the exhibition theme, After Nature (which will also conjure, for Anglophones, the title of an early prose poem by W.G. Sebald; Nach der Natur for Germanophones), given that it is located under a sand dune on a beach in the Aranya Gold Coast Community development in Hebei. Accordingly, the exhibition, Organised by UCCA curator Luan Shixuan, aims to explore the natural world as it is defined and (increasingly) shaped by humanity. More pressingly, Luan locates the show in the context of a recent UN Climate Change report that forecasts significant climate-related crises by 2040 unless current carbon emissions are reduced. Indeed, in some ways any exploration of this theme is all about context. The new Aranya development bills itself as ‘an innovative art vacation destination’ (the costal area was previously famous for being the place where China’s leaders went on summer retreats). Beihai, down in southern China, is predicted to be the world’s fastest growing city over the next few years; meanwhile China is seeking to massively reduce the rampant air pollution (which peaked during the early 2010s) that has accompanied its explosive growth since the 1980s. As to the exhibition itself, that features the work of nine Chinese artists born between 1942 and 1988. Among the works by the older generation, look out for Liang Shaoji’s ongoing collaborations with silkworms (and for more on those, refer to ArtReview Asia’s spring 2015 edition), while at the other end of the generational spectrum you’ll want to pay attention to Trevor Yeung’s explorations of the acanthus tree as represented in art and proliferated by colonialism.

Mori Junichi, Mizuma Art Gallery, Tokyo, through 24 November

From trees to mountains (but still clinging to context) and Portrait of the Mountain, Japanese artist Mori Junichi’s first solo exhibition in four years, currently on show at Tokyo’s Mizuma Art Gallery. The mountain in question is Konpira, located at the centre of the Nagasaki Prefecture. Back in 1945, as local residents fled the atomic fallout following the US bombing of the Prefecture’s capital for the ‘safety’ of the mountain, where many of them died of exhaustion. Meanwhile, local legend has it that the mountain deflected some of the nuclear blast, leaving the towns located at its base (among them the artist’s hometown) relatively unscathed. At the centre of Mori’s exhibition is a new, black-marble sculpture that articulates the connections the artist made between the inclined surface of the mountain and the drapery on a pietà he had seen. Mori’s own version of the ‘postnatural’ seeks to embody the natural, the human and the divine in a single form.

Eric Baudart, Edouard Malingue, Hong Kong, through 24 December & Samson Young, Edouard Malingue, Shanghai, 6 November – 23 December

Playing with form lies at the heart of the work of Eric Baudart. His Cubikron 3.3 (2017), exhibited as part of last year’s edition of Xiàn Chǎng, is a grid made up of mattress springs, that at various times and from various angles resembles (sometimes separately and sometimes simultaneously) a stack of horizontal planes, a cuboid whole and a shimmering cloud of motion. All in all it looked like an experiment produced by a crazed geometrician. This winter the Frenchman is exhibiting in Hong Kong with a solo exhibition titled one, maybe two Parsecs at Edouard Malingue Gallery. A parsec is a unit of distance roughly equating to 3.26 lightyears (and also the measurement of choice for Han Solo’s bragging in various episodes of the Star Wars movies), so perhaps we can expect a dose of equally out-there astronomy to join the geometry. May the force be with him. Over in Malingue’s Shanghai gallery one of Hong Kong’s favourite sons, artist–musician Samson Young, will display a new work, titled The highway is like a lion’s mouth.

Heteroglossia, How Museum, Shanghai, 7 November – 17 February

Meanwhile, at Shanghai’s How Museum, Young’s work is included in a group show aptly titled (given the artist’s previous work with choirs and multiple voices) Heteroglossia. Expect the theme to encompass something beyond issues of multiplicity and difference in voices and language and to expand to articulations of difference and similarity as seen in, for example, in the rise of globalism and nationalism. Alongside Young, look out also for works by Cao Fei, Ho Tzu Nyen, Fiona Tan and Wang Qingsong. And just in case you were in Shanghai and somehow managed to miss him, Young also has a work in the Shanghai Biennale, where you can experience the latest instalment of his Muted Situation series – No. 22: Muted Tchaikovsky’s 5th (2018), for which the artist invited the Cologne’s Flora Sinfonie Orchester to play Tchaikovsky’s work with the musical notes muted so that the background noise of the performance comes to the fore.

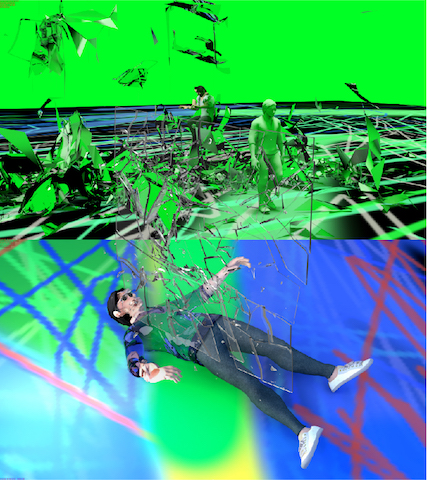

Cao Fei, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein Westfalen, through 13 January

There’s nothing muted about Young’s fellow Heteroglossia exhibitor Cao Fei however, who, even as her first Asian retrospective exhibition continues at Hong Kong’s Tai Kwun Centre for Heritage and Arts (btw – as you might have begun to notice, the same few artists seems to circulate with increasing frequency through exhibitions of Asian art, which is another reason to keep looking for what you don’t know), sees a new version of her 2016 MoMA PS1 retrospective roll into K21 in Düsseldorf. There you’ll be able further to explore her continuing journey through the worlds of digital media and networked society and the increasingly blurry lines between fantasy and reality that it engenders. Some might call that a chronicle of contemporary escapism, others might look to the exhibition to chronicle the ways in which digital habits and digital technologies have evolved since Cao’s COSPlayers (2004) first hit the scene. What’s without doubt is that Cao remains one of the sharpest observers of the impacts of globalism and technology on contemporary life.

Marcel Broodthaers, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, Moscow, through 3 February

When it comes to pioneers of the blending of fantasy and reality (in a predigital world), Belgian Marcel Broodthaers was something of a master. He was big on embracing nature within the arms of culture too. As a Belgian and conscious of his nation’s stereotypes, he used mussels and the cooking of them to demonstrate this. Of his Casserole with Closed Mussels (1964), a pot with a column of (uncooked) mussels about to burst through its lid he said, ‘The bursting out of the mussels from the casserole does not follow the laws of boiling, it follows the laws of artifice and results in the construction of an abstract form.’ When humans interfere with nature, they abstract it and the results can be justified by an appeal to art. Or something like that.

In any case, Moscow’s Garage Museum of Contemporary Art is marking the tenth anniversary of its founding with a retrospective of Broodthaers’s work. It’s fitting really, given that the artist (who only began making works of visual art for public consumption as he approached his fortieth birthday), spent so much of his time engaged with what would these days be described as forms of institutional critique. Indeed, in 1968 he created his Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles, an institution with neither a venue nor a collection that tended to produce pop-up displays of reproduced artworks, shipping crates and wall labels (the business and infrastructure of a museum rather than its displays). In 1970, the artist announced the display of the museum’s ‘Financial Section’ at that year’s Cologne Art Fair, declaring that the institution was for sale ‘on account of bankruptcy’, while also producing an (unlimited) edition of gold ingots stamped with the museum’s eagle logo. No buyer was found for the museum, but the ingots continue to stand for the artist’s exploration of art’s material and conceptual worth, and the confusions that result from trying to measure or equate the two (further explored in his Poèmes industriels – a series of plastic plaques that mimic both advertising strategies and the grandiose name-plates of institutions, while drawing on the artist’s talent for language gained during his former career as a poet and journalist). Art museums, after all, have a kind of heteroglossia of their own…

Read Part II of ArtReview Asia’s picks here

From the Winter 2018 issue of ArtReview Asia