Where does the artist’s fascination with dogs spring from? And what does it tell us about her longstanding preoccupations with death and mortality, desire and difference?

Back in 2014, Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook concluded a poetic lecture at the SculptureCenter in New York by talking about the dog with whom she participated in Documenta 13. As photos of a Thai ridgeback flashed onscreen, she recounted finding “a thin black dog, hit by a car, lying wet with rain in the middle of the road” in 2011, being bitten on the hand after picking it up, then spending 25,000 baht on an operation to fix its legs. Her account of a spontaneous dog rescue then pivoted to the story of how Ngap (meaning bite), as she named him, later accompanied her to Kassel, where, for Documenta 13 in 2012, they lived in a fenced-off house in Karlsaue Park for three weeks. This story was then followed by clips from videoworks featuring her dogs – including one in which she and Ngap sit watching Thai soap operas and harrowing news clips (The treachery of the moon, 2012) – and a Q&A session in which the first query was, naturally: “What’s the significance of all the dogs?”

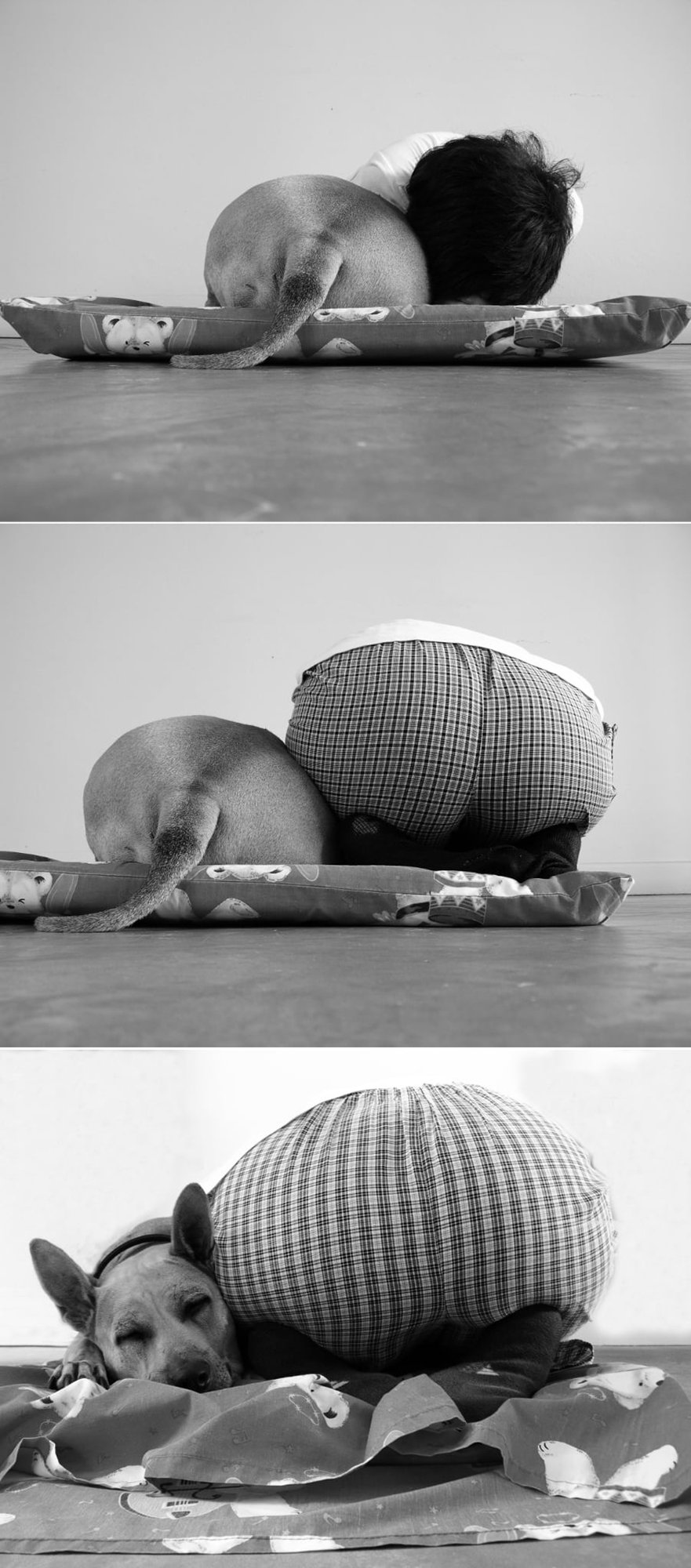

Part one of The Bouquet and the Wreath, a two-part survey of the Thai artist’s 45-year career, also begs the question of from where this fascination springs, and of what it signifies within the context of her enduring preoccupations with death and mortality, desire and difference (preoccupations that have also led her to work, controversially, with unclaimed human corpses and the clinically insane). Dominating the large hall of MAIIAM Contemporary Art Museum in Chiang Mai is Ban Wang Hma (Dogs’ Palatial Castle) (2025): a crooked castle made of wood planks, the distressed facade of which is painted with climbing flowers and oversize dog faces belonging to the 17 strays the artist cares for at her home in rural Chiang Mai. Meanwhile, scattered throughout the show are dog-related artworks and accessories: 13 lifesize dog sculptures (starving, playful, sleeping), installations that include dog hair as material and a vitrine of used dog splints.

Rasdjarmrearnsook’s reply to that question when it was posed in New York was illuminating: “When I was younger, I believed that art was an exit for life – an exit to somewhere purer, cleaner, more innocent. And when I grew older, I realised that it wasn’t the case. Caring for dogs who are hungry, sick or wounded became special for me.” And it remains so: yet more dog-related elements of the current survey suggest that caring for dogs continues to displace, or become a part of, her artmaking.

Parked in front of Ban Wang Hma are three dog pens on wheels, atop one of which sits a donation box and an invitation to ‘support voluntary care for stray and abandoned dogs and other animals’. Nearby, a sign incorporating a QR code advertises a concurrent Ban Wang Hma project: ‘Araya has rented a mango orchard of over 400 square metres, which is near her home and studio, and planted abundant flowers in its fertile soil. In this lush space… a small building with a terrace offers visitors a place to sit, eat, cook, and converse with both humans and dogs, all while taking in the beautiful views of the grasslands and mountains.’ The only condition, it adds, is ‘No Dog, No Entry’: ‘Visitors must either bring their “own” dog or “borrow” one of the 17 residents.’ Beneath this, a snaking list of their 17 names begins with that of Ngap.

An understanding of the local context can help us clarify and parse Rasdjarmrearnsook’s bond with dogs – as it can all her encounters and dialogues with marginal subjects. Take the transgressive corpse videos of the late 1990s and early 2000s, for example, in which she reads poetry to cadavers, dresses them or tries to converse with them. Her best-known works, these are indebted to Thai funeral practices – namely their conventions of intimate attachment and engagement with the dead – but deviate from Buddhist orthodoxy and its male dominance. Similarly, Rasdjarmrearnsook’s dog works, which sometimes veer towards anthropomorphism, resonate with Thai society and karmic belief: her dogs’ role as ‘active protagonists’ and ‘kin’ finds a strong affinity in Buddhist dāna (giving) and temple life, wherein monks share food, space and status with the common maa jonjad (stray dog). But beyond this specific cultural register, the artist’s empathetic alliance with Thai street dogs also relates, as former SculptureCenter curator Ruba Katrib wrote in 2014, to a ‘larger ethical arena’ that is bound up with gendered histories and hierarchies of being (philosophers of the Enlightenment – men such as René Descartes – got to decide that nonhuman animals are inferior, Katrib points out). Like corpses, dogs in her practice appear as avatars of otherness within a worldview that is partially ecofeminist, partially Theravada Buddhist, yet bound to neither.

Then again, maybe the incursion of her companion species into this survey should be treated more lightly, or taken at face value, because it simply speaks to an ongoing recalibration between art and life. In an interview the morning after the opening (during which three of her dogs sat in the pens as guests of honour), Rasdjarmrearnsook, who is now in her late sixties, and I speak extensively about her adopted pets – almost as much, in fact, as we do about her desire to exit the artworld. When an invitation to participate in an exhibition or biennale lands in her inbox these days, she replies with a variation of the following: “I am trying to retire from being an artist, so I’d like to explore or think about a previous work that matches your exhibition concept. And please note: I won’t do a new commission for the project… because I am trying to retire.”

That was the intention with this show, her first largescale survey, but obligations intervened. When I reply that “trying to retire” leaves open the possibility – the tantalising prospect – of failure, she says she broke her rule about new work because she had “a responsibility to do this castle”, which is inspired by both her Documenta 13 project and an early intaglio print of a European castle. Installed permanently on the wall behind it is a “giant red work” by another artist: Thasnai Sethaseree’s Cold War: the mysterious (2019–22). To open the show with anything smaller than this giant castle – which now partially obscures Sethaseree’s billboard-size paper collage, a cacophonous explosion of colour and graphic elements relating to the Cold War in Thailand – would have looked “poor”, she explains. This desire to make a big impression also extended to the producing of a new eight-channel video, for which she spent two years sifting through and remixing past works (its working title: “video bomb”), as well as the hyperreal dog sculptures, the making of which she found emotional. “I cried so often,” she says.

It remains unclear how the second chapter, which opens at the Jameel Arts Centre in Dubai this November, will unfold, but the Chiang Mai chapter is a boldly structured retrospective: the opening statement makes no mention of Rasdjarmrearnsook’s biography (or pending retirement); there is no chronological progression of style or themes. What we get instead is an amorphous show that begins by alluding to the ‘immense philosophical questions’ she has dwelt upon and asks us to find them in the substance of over 70 ‘playful yet somber’ artworks spanning prints, sculptures and video. According to the curators, this heuristic approach serves to decentre the personal events often cited as being formative and fundamental to Rasdjarmrearnsook’s disposition and artmaking, in particular the big event: the death of her mother when she was only three. “Through the course of making this show, I’ve begun to try and find other ways of thinking about the sense of loss and mourning and grief that runs through the work,” said Roger Nelson, who worked on the show with MAIIAM curator Kittima Chareeprasit.

Still, while Rasdjarmrearnsook’s personal story is not foregrounded, her voice as a writer is ever present – a guide of sorts. Over the decades, she has participated in countless exhibitions and biennales across the globe, but a little-known fact in the Anglosphere and international artworld is that she is perhaps best known as an author of novels and nonfiction in her native Thailand. And a prolific one at that. In each room here, Thai and English wall labels featuring her fresh responses to the works on show or excerpts from her novels and exhibition catalogues – some of them approximating what art historian and curator May Adadol Ingawanij has called Rasdjarmrearnsook’s ‘Thai-language baroque’ – allow elements of her backstory to be gleaned.

For example, a remade version of an early installation, Has Girl Lost Her Memory? (1994/2025), comprises a black bed-frame upended against a corner of a room and surrounded by a pile of shredded corn husks. Its caption discloses that, during Rasdjarmrearnsook’s rural childhood, this simple material was used to make artificial flowers for funerals (including for that of her mother), before she offers her take: ‘What memory might these discarded husks carry of a woman?’ she asks. Elsewhere, in a room dominated by morose prints produced during her studies in Thailand and Germany during the 1980s and 90s – intaglios, photo etchings and heliogravures – she writes of ‘a young woman in her early twenties, uncertain of where to anchor her art’, and whose ‘sensitivity to the landscape’s quiet presence became a source of solace’. Upstairs, in a room where past publications can be browsed, an early tempera work covered in asemic Thai script (Writing has Begun Now, 1992) sits near a book excerpt: ‘Writing begins here. It’s a conversation that begins from an artmaker who puts her artwork before her audience.’

This conversation (between audience, artist and author) makes the show feel informal and open-ended rather than magisterial and definitive – which is entirely in keeping with the exaggerated poetic licence and fragmentary literary nature of Rasdjarmrearnsook’s practice. As a wall text points out, she resists ‘stiff definition’. The omnipresence of her voice also shows, rather than tells, us that this practice comprises intertwining and interdependent visual and textual components – that the artist is indivisible from the writer, and vice versa.

The mixing of periods and mediums, meanwhile, elevates those that have, amid the flurry of institutional and scholarly interest in her videoworks, been sidelined. According to a 2019 Afterall article by the academic Clare Veal, the artist’s installations from the 1990s are often framed as a ‘developmental stage’ that was superseded by ‘more complex explorations of the relationships between art, life and death’. But reading them from within the perspective of later works can, she argues, counter this by yielding ‘differently sited conceptualisations’ of the ways in which they speak to and from the individual and the social.

That framing resonates with my reading of the theme of death, which gnaws and festers in old and new works alike, but the meaning of which is unsettled, impossible to conclusively pin down. In recent years, Rasdjarmrearnsook’s long-standing proximity with death has taken a cheerless turn – several art projects have alluded to her desire to end her life with assisted suicide, and this ‘exchange life-art project’ with a fundraising component (for dogs, you may be surprised to learn) has a website. (This is not a drill, nor a performance, she insists when I ask her to elaborate – psychologists were consulted, and her urge to die is real.)

In the exhibition, though, in which this disconcerting desire is not disclosed, death is a social construct, or condition, marked by its pliancy rather than its finality. It transmogrifies into something savage in Death with Cancer (Rebirth) (1993/2025), an installation resembling a crime scene that comprises a bed frame surrounded by the intravenous tubing salvaged from her late father’s bedside; it is lyrically broken down into three melancholic chapters as a dog sits on the bed next to the artist in the video Inspiration Comes from Different Sides of the Same Sky (2008); and it is the subject of a nourishing, and at times darkly comic, lecture given to the dead in her famous video series The Class (2005):

––I would like to suggest that maybe there is more freedom in dealing

with death in art and literature. In my opinion, art can play with

the meaning of death. Art can approach it from different angles.

And death becomes a feather in the wind.––

As for the new video installation, which comprises eight projectors splayed around the walls, floor and ceiling of a large room, it upends the mood of past videos to create what Rasdjarmrearnsook calls ‘an unsettled zone of tension’. Shifting operatically between delirium and stillness, The Same Old Karma Landscape (2025) blends phantasmagoric scenes lifted from past videos – from pigs being slaughtered in an abattoir to dogs enjoying a backyard barbeque – with old Thai songs and abstract shots of storms and sunsets. Mortality, it hints, is a force of nature bound up with the small joys and sharp vicissitudes of living. Similarly bittersweet are the dog sculptures dotted here and there, whose gamut of expressions – denoting happy and unhappy states – hint at corporeal (if not ethical) equivalences between us and other animals. In short, the show’s continuum of emotions and circling of existential themes resonates with both the celebratory and funerary connotations of its flora-inspired title.

Arguably, a downside of this format is that all-important connections between her work, her background and her professional development (such as the 30 years she spent teaching at Chiang Mai University, where she founded a pioneering multidisciplinary art programme) are attenuated, or downplayed. But by dint of its staging in Chiang Mai, where she and many of her peers live and work, The Bouquet and the Wreath – especially Ban Wang Hma, with its dog paintings and offsite meet and greets with Ngap and friends – still feels enmeshed in the all-important context of Thailand, including the social world of its art scene.

As a writer, Rasdjarmrearnsook has occasionally sought to spell out the differences between male and female artists, especially those involved in Thai art schools and art circles. Sometimes these differences have been articulated lyrically in terms of imbalances: in a 2002 exhibition catalogue she writes of studying at an ‘old academic institute in Bangkok’ (Silpakorn University) where ‘the number of female students was like a sliver of cake’ and the rest ‘so large that it could never be eaten up’. And sometimes they have been articulated bluntly in terms of temperament: during the mid-2000s, a column she penned for a Thai magazine – which saw her adopting the male pronoun ‘phom’ and was published in English translation in 2022 – revealed both a scepticism about political art in general and a belief that male artists (or ‘little boys’, as she irreverently calls them) use ‘art as a safe space for rebellion’ more than women artists do. ‘Is that because male artists exist outside the conditions of life?’ she wrote in Matichon Weekly magazine. ‘Or is it because women artists exist under these conditions more?’

During our conversation, Rasdjarmrearnsook reveals that her castle is meant to draw attention away from Thasnai Sethaseree’s “giant red work” on the far wall: a strident political piece that falls firmly into the rebellious-male-artist camp. But standing before them, I sense more than pragmatism – a concretisation of the gendered sociocultural dynamics that play out in her writings (another strain of her thinking distils the female-male artist binary down to a distinction between ‘poetry’ and ‘awareness’, while her translated columns are a dialogue between ‘She’ and ‘He’). By obscuring Sethaseree’s collage, and by mawkishly invoking a bare life far removed from restive politics, Rasdjarmrearnsook’s castle seems to answer back, or counter it.

With a white picket fence drawing a border between Ban Wang Hma and Sethaseree’s painting, it is tempting to view this installation in starkly feminist, and yes biographical, terms: as a metaphor for a female artist and teacher who struggled for space in a patriarchal Thai artworld and academic life, and who is now renouncing both by retiring to bucolic dog land (an aim that could well be a performative conceit: ‘trying to quit being an artist’ is mentioned in the 2008 video, and she is also participating in the forthcoming Thailand Biennale Phuket). But stepping inside the castle – where a label quotes Rasdjarmrearnsook as saying it ‘reflects a persistent need for shelter, both real and imagined’ – problematises this simplistic interpretation.

Playing on three mounted monitors is a videowork (Chanting for Female Corpse, 2001) wherein our lateral view of an old woman’s partially exposed corpse submerged in formaldehyde resembles the contours of a landscape. And on the floor nearby is Tata (2025): a lifesize model of a (living) brown beagle lying on its back with an expectant look, as if hoping for a belly rub. Here is a shelter – and by extension an art practice – where the living and the dead, love and yearning, beauty and ugliness, skin and fur, writer and artist, text and image, trying to retire and failing spectacularly at it, all coexist. Here is a safe space for a different kind of rebellion, where otherness and creatureliness and the unabridged conditions of life appear very much at home.

Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook’s The Bouquet and the Wreath is on view at MAIIAM Contemporary Art Museum, Chiang Mai, through 25 May. Part two, at Jameel Arts Centre, Dubai, opens 5 November and runs through 15 March. A parallel exhibition, Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook: the Same Old Karma, is on view at 100 Tonson Foundation, Bangkok, through 18 January

From the Autumn 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.

Read next: How Thailand became a refuge for displaced Myanmar creatives