Lawrence Alloway (1926–1990) was an English art critic and curator best known for coining the term ‘Pop art’ during the mid-1950s. Having been a leading member of the Independent Group in Britain, which met at the ICA, where Alloway was assistant director, he moved to America in 1961. He was a curator at the Guggenheim Museum, New York from 1962 to 1966.

On the occasion of its seventieth anniversary ArtReview republished an abridged version of this article from April 1959 in the March 2019 issue.

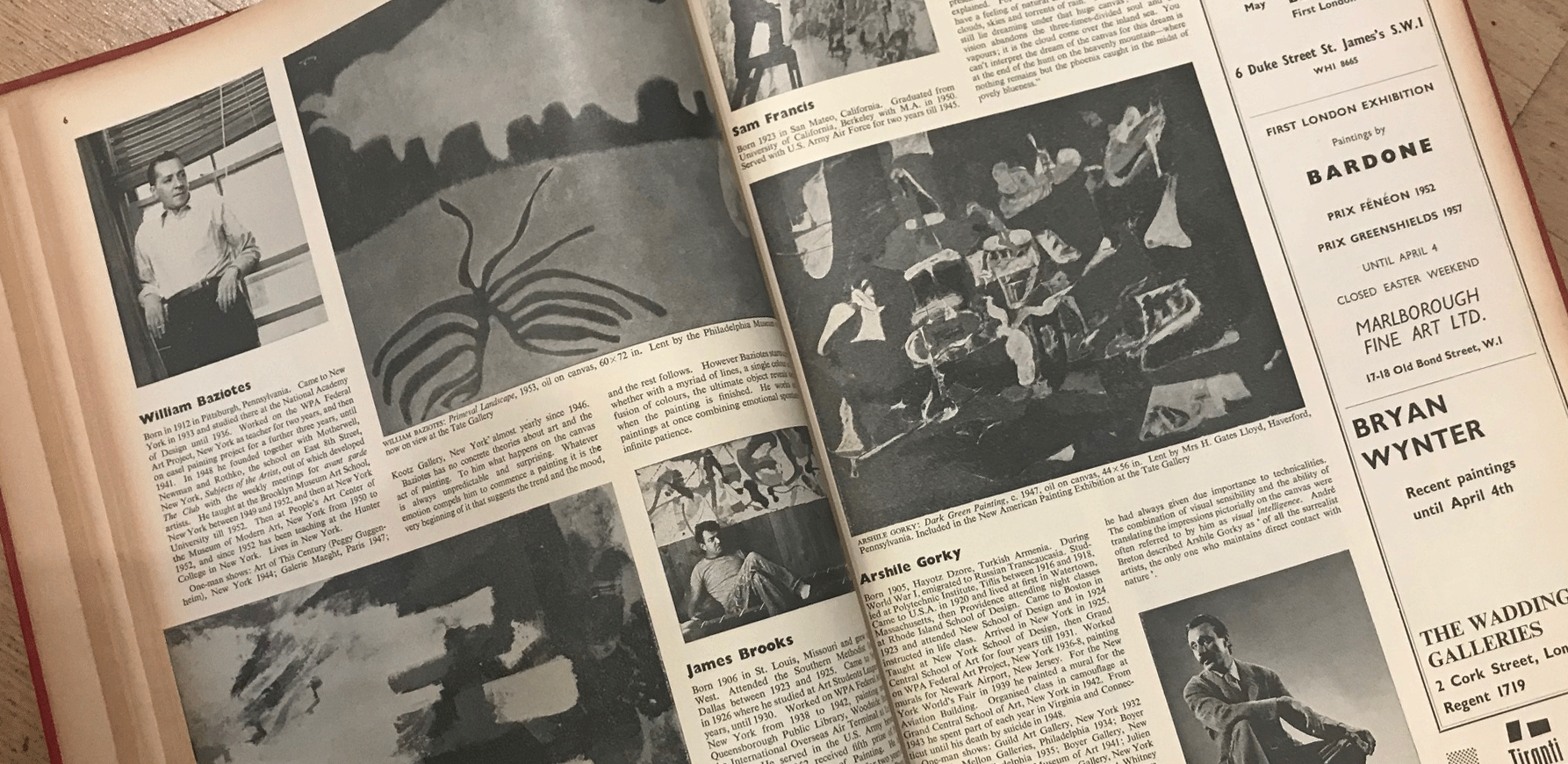

Compare The New American Painting at the Tate Gallery with the recent exhibition of Russian Painting at the Royal Academy. The Russians did not trust their best art out of the country: the icons and the ‘revolutionary genre’ were, so the people who dig Russian art said, second-level specimens. We were not given a ‘best of its kind’ exhibition: small versions stood in for big pictures; key works stayed at home. This attitude of withholding the goods is opposite to the spirit manifested by the American exhibition. The seventeen artists are represented by first-rate works in every case; even the artists that one likes least are represented by the ‘best of their kind ’ (only Pollock is patchily seen, but then his big one-man show toured currently with The New American Painting). The generosity and seriousness of the International Council of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, is conspicuous in this major exhibition.

Leaving out Sam Francis, Grace Hartigan, and Theodoros Stamos (all in their 30s) the artists, the big were born between 1903 and 1913. It is a generation after Picasso and before the post-war swarm. Who could be put into an equivalent British exhibition? I can think of Sutherland, Pasmore, Scott, Bacon, Hilton, Piper, Moynihan, Ceri Richards. It is clear, even though the British Council or the Contemporary Art Society might enjoy such a show, that the sense of discovery and purpose, power and vitality that marks the American exhibition would be, to put it mildly, missing. If one put on a European version of this age-group, how would it compare? Obviously it is no good listing everybody between 44 and 55 so I will cut it down to the some I have faith in: Giacometti, Dubuffet, Fautrier, Fontana, Jorn. If I have forgotten anybody it wouldn’t change the argument much.

Europe cannot match Pollock, Rothko, Still, Newman, De Kooning, Kline, Gottlieb, Guston

The point is: Europe cannot match Pollock, Rothko, Still, Newman, De Kooning, Kline, Gottlieb, Guston (and, by the way, Hans Hoffmann). Most aspects of New York abstract painting have been very well covered. Consider that phase in the 40s in which form (an instrument of clarity and solidity between the wars) was being invested with multiple significance. Baziotes and Gorky are helpfully hung together, which brings out their common biomorphism. This can be described as Andre Breton did, in one of his best later writings, by calling it a use of ‘hybrid form in which all human emotion is precipitated ’. Often, however, it is not much more than a custom of sexualising everything the artist can lay his hands on, a vice of Americans hit by decadent surrealism. But Gorky does it with a terrific elegance that cons us into acceptance of that old viscera and those organs busting out all over. Gorky, like Baziotes and Pollock, developed a mature personal style in the mid-40s, before Kline, De Kooning or Rothko. Baziotes learned from European fantasists such as Klee and Miro but set their hybrid forms (it’s a bird, it’s a man, it’s a superflower) in a stiff format with silvery colour reminiscent of Arthur Dove. He has remained within the limits of this thesis made in the 40s, elaborating a patient iconography of the biomorphic kingdom. Stylistically Gorky and Baziotes represent a time when surrealist forms were being converted to new puposes. What the new purposes were can be seen in De Kooning’s Painting (1948) in which the forms, heavy, blunt, rounded, really are referentially all-purpose and not, as in Gorky, mainly sexy. Pollock in his drip-paintings created an image of advancing space.

The presence of the paint on the top of the picture surface (where else?) was stressed by thickness of pigment, linear overlaps, metallic puddles and ribbons, so that the surface is pushed at the spectator, not hollowed away from him (as it is in De Kooning and Guston). The basic assumption is of a space effect created by the literal area of the picture as it occupies space, our space, not an imagined pictorial one. Although different from one another Newman, Still, and Rothko have in common the creation of this kind of literal, participative space (in which they have been joined recently by Gottlieb in the Burst series). This is probably the most radical line in the various threads of New York painting, a major resolution of 20th century intuitions about space and that obsession with surface which has nagged everybody since Gauguin and Mallarmé.

Rothko’s five paintings show that Dr Sandberg of the Stedelijk Museum, who thinks that if you’ve seen one Rothko you’ve seen them all, is good and wrong. The Rothkos paraded on a wall at the Tate Gallery show colour variations and changing proportions which are the clearer and more individual for the simplicity of means. Light, which glows in the earlier and glowers in the later paintings, never felt more like ‘visually evaluated radiant energy’, part of a wave-band that includes hard-radiation. Still, in his three thick paintings, in which the pigment is scarred and wrinkled, and one thin one in which the paint is lean and dry, defines the stretch of canvas as the reach of space with a rigour and control that does not preclude a sense of unknown forms appearing. Still was not included in two books about American abstract art that came out in 1951 (one by A.C. Ritchie, one by T.B. Hess) though all the works in the current show were painted by then. Recognition of Barnett Newman has taken even longer (though three of his pictures in the present exhibition date from 1949): his presence in The New American Painting is a surprise to everybody (including some of the staff of the Museum of Modern Art, probably) but he is at the top of the show. His economical means and deadpan technique makes everybody else’s work risk fussiness and elaboration. His four pictures (one relegated to the hall – don’t miss it over the catalogue table) are not geometric art (see his statement in the catalogue) though they may look like it at first. His divisions of the picture plane are pauses in his continuous fields of colour, control factors in the expansion of the picture in the spectators’ perception of it. One feels alone with these paintings: you look at them as the last man might look at the world. (It is good to see Tworkov in the exhibition, an able painter whose recent work has acquired a considerable grandeur).

This exhibition should make opponents of American art (of whom there are plenty in the newspaper offices, art schools, and drawing rooms of London) realise that it is not all one big splash of paint. The New York School (Motherwell’s phrase) is as varied and complex a body of artists with different ideas and performances as any first-rate group can show. Rothko, for example, named ‘memory’ as one of the obstacles between a painter and getting clarity. To Guston, on the other hand, though aware of the demon process, forms ‘possess a past’ and one of the revelations of the exhibition is how this ‘past’ works in Guston’s painting. (Both statements are quoted from the catalogue which prints numerous apt first-person statements by all the artists except Francis and Stamos who go in for god-like double-talk.) Guston’s 1954 Painting is a kind of Impressionism on a grid, done in a style descended from Monet’s Morse code. In the later works, the grid has been clenched and folded, the forms thickened, into an allusive density. These forms are nourished on ‘memory’ like an orchid on flies.

Barnett Newman’s economical means and deadpan technique makes everybody else’s work risk fussiness and elaboration

Almost the only artist to suffer from the omission of a significant phase of his work is Gottlieb. None of his pictograph period is on view: only the last gasp of this style is present in Tournament in which colour sparks like fireworks across the wall which had carried his symbols. Two examples of his Imaginary Landscapes are included, however, strong and glossy as a puma, and the recent Burst in which his earlier symbols have expanded into majestic forms, a crisscrossed black, a swollen red circle. In these new works Gottlieb has achieved his own personal version of the radical simplicity of means that characterises Newman, Still, Rothko, and Kline.

Kline, unlike the other artists who go in for radical simplification has no place for post-symbolist mysteries (which Sam Hunter has detected in Still and Rothko, for example). He did in the 40s what Roger Coleman has called a girder painting, doing pictures of the El, fireescapes, etc. In his black-and-whites since 1950 urbanism has been generalised into forms that connote rather than denote the city and trains. Like other American painters he makes (1) pictorial structures which are not ‘ pure ’ but loaded with outside references and (2) his references are markedly shaped by the gesture of the artist. This mixture of reference and gesture makes old-fashioned the argument between pure abstract art versus nature-based realism (which is still believed in its primitive forms in much of Europe). The once-vital opposition has been assimilated into a third term by Kline, as it is by De Kooning in February. Kline’s fine paintings in the show (though stopping short of the later cloudy and coloured paintings) are of superb quality, especially Wannamaker Block and Garcia.

Sam Francis is a problem. In Europe he is made too much of (I have heard people here rank him with Pollock, Still, Rothko) and in America he is under-rated: he can ever be overshadowed by New York resident Norman Bluhm, who does Francis-type pictures in a dogged, brute way. In this exhibition, where Francis is put in his place with Stamos and near Hartigan, there is support for the view that he was best in the I earlier works in which small units were statically repeated nearly all-over the canvas. The later work of 1956, a cabaret of blazing orange, fails to stay alive and fixed; the change from small puddles to arm-length gestures destroys the patient, delicate rhythms of the earlier works (which look every bit as good as they always did).

In America it is often hard to hear a good word for the Museum of Modern Art but in Europe, which has only one decent modern museum, we can only marvel

No other country in the world could put on an exhibition of post-war painting to equal The New American Painting and no other museum in the world could have arranged it so well. In America it is often hard to hear a good word for the Museum of Modern Art but in Europe, which has only one decent modern museum, and that in Amsterdam, we can only marvel at the resources and intelligence of the MMA. This does not mean that the exhibition as it stands cannot be faulted. Since the scope of the show is meant to display, to quote Alfred Barr’s judicious introduction, ‘the central core and the major marginal talent’ of Action Painting/Abstract/Expressionism, Hofmann’s absence is absurd. He towers above about half the painters in the show and is level with most of the others. His absence makes one more critical than one would otherwise have been of the presence of Hartigan (OK with the MMA for years), Stamos (whose vapid atmospherics are a big drop in quality from the rest of the show), and Francis.

Given the Tate Gallery’s accommodation hanging probably had to be pragmatic; even so it fails to pass the test of pragmatism. It doesn’t work. The presence of Still sandwiched in between Gorky and Baziotes made one sympathetically aware of why the artist loathes mixed shows. The proximity of Newman and Guston is no better, a horrible collision of incompatibles (and not a balance of North Pole and Tropics, or whatever was intended). Does hanging matter? I think it does, because properly done it releases the visitor’s power to make connections. Some of the works, however, are hung in ways which make it very hard to grasp the stylistic connections that exist between Gottlieb and Tomlin or between Still, Newman, and Rothko. De Kooning is (unforgivably) cramped into a narrow space by a doorway; Motherwell could have gone here, because his wall-paintings (such as the Elegy for the Spanish Republic XXXV) are summary in treatment, not complex and demanding like De Kooning’s tough and intricate works.

Originally published 14 March 1959 of ArtReview, then styled Art News and Review