It’s a loving heart-breaking portrait of a family afflicted by terror and tragedy, yet it’s told in a candid unsentimental way

Since a Tennessee school board removed Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel Maus (1980-1991) from its curriculum, chaos has ensued. Some conservatives have disputed whether it was banned at all, merely removed from the syllabus for nudity and swear words. Meanwhile Whoopi Goldberg was suspended from ABC’s ‘The View’ for ill-conceived comments during a discussion of the issue. The author himself called out the book’s ‘Orwellian’ treatment. The book shot to the top of bestseller lists. The censors, against their own intentions, succeeded in pointing out what’s worth reading.

The question of how to begin to comprehend the vast depths of the Holocaust is a fraught one that survivors, seeking to bear witness, have long wrestled with. The clarity and integrity of Primo Levi’s writing, for instance, is haunted by survivor’s guilt, ‘We are those who, through prevarication, skill or luck, never touched bottom. Those who have, and who have seen the face of the Gorgon, did not return, or returned wordless,’ he wrote in 1986’s The Drowned and the Saved. By contrast, the dark enigmatic poetry of Paul Celan defies rationality as if to suggest a crime as colossal as the Holocaust, containing millions of stories, many lost forever, cannot and perhaps should not be ‘understood’. Any glimpse then of a system of atrocities arguably incomprehensible in scale and horror is both crucial and incomplete. It’s a question that remains unsettled and unsettling.

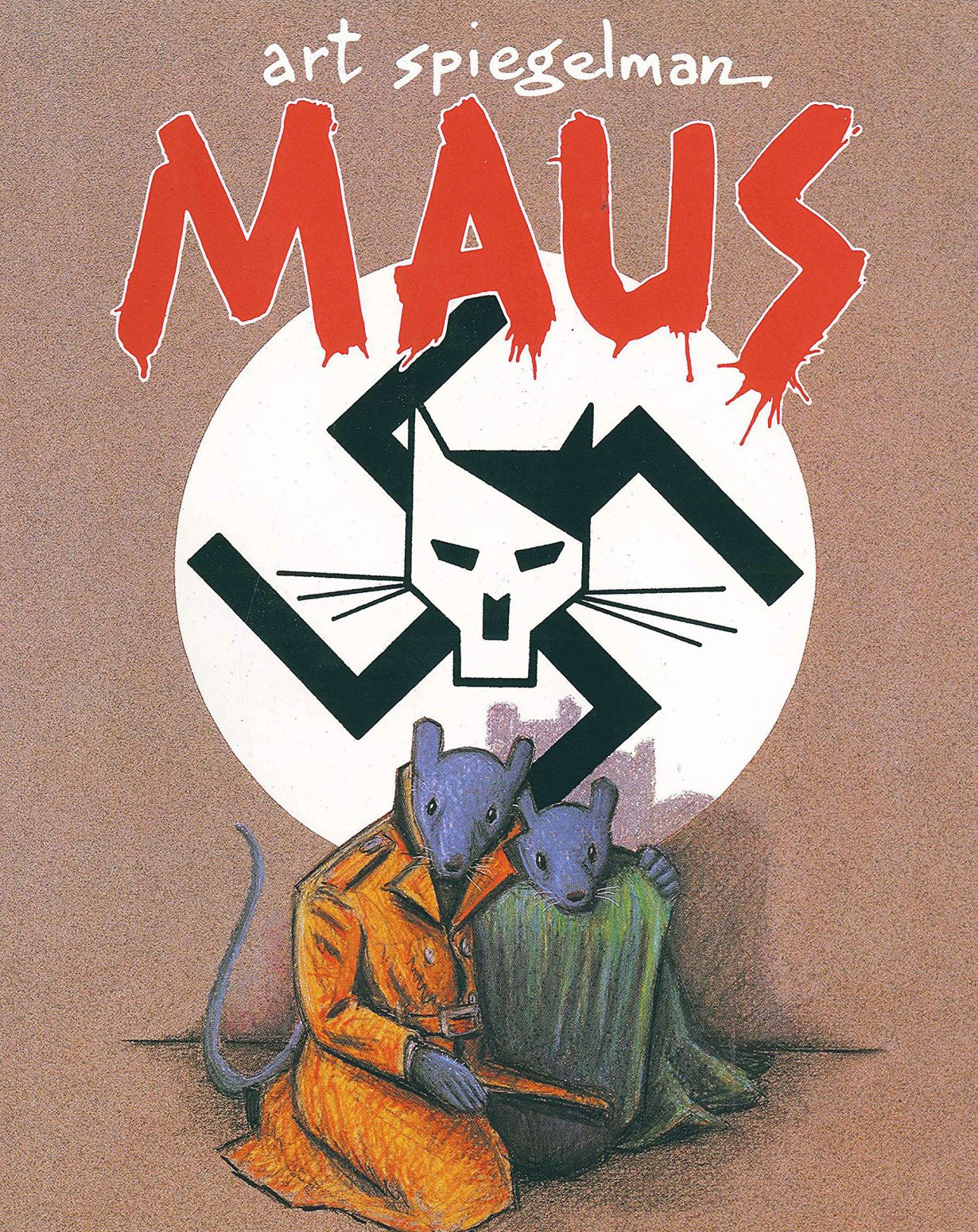

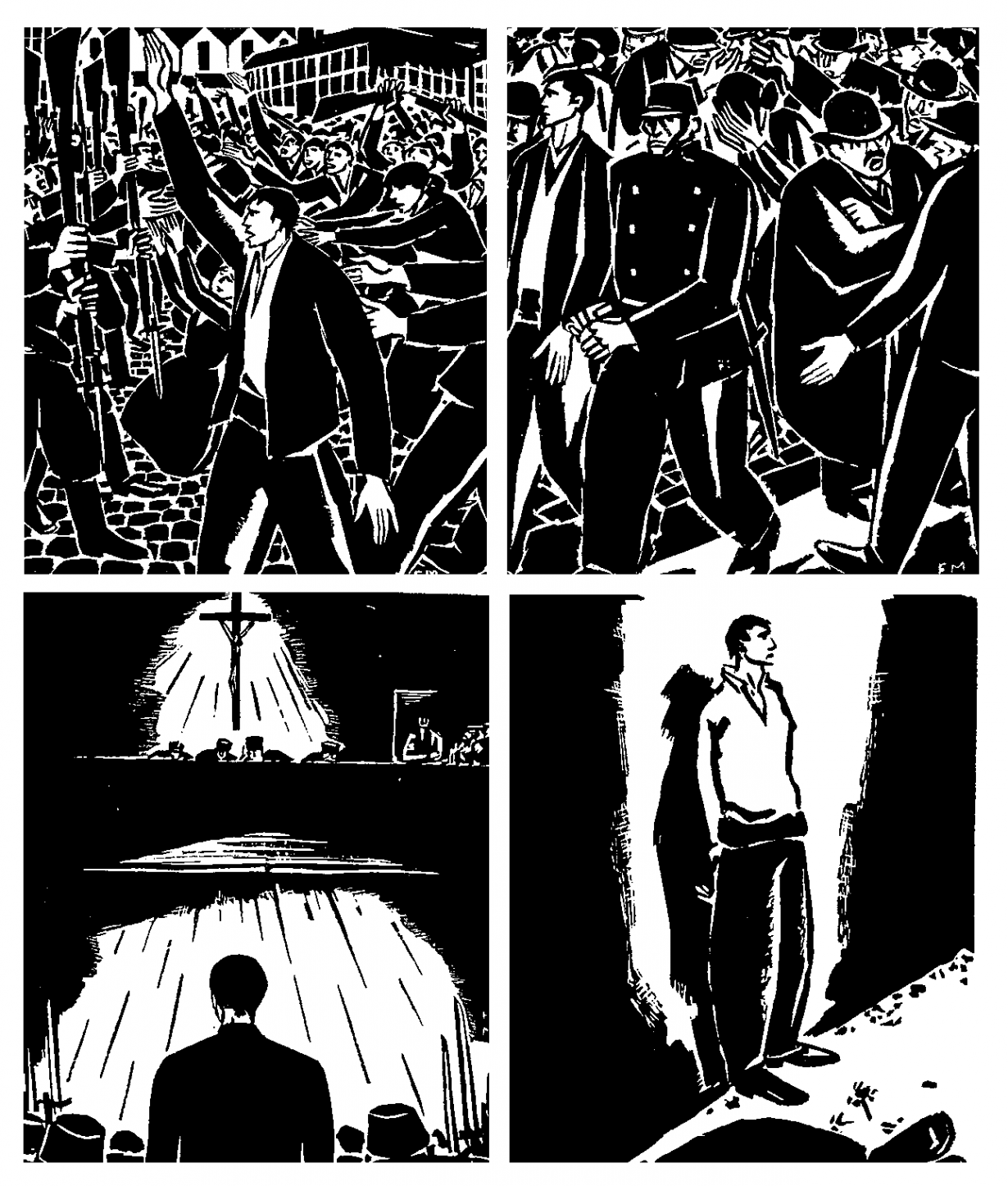

A large part of the appeal of Maus is its accessibility, a quality that appears, like the clear prose of Levi, to be an ethical decision. It’s drawn in a simple childlike way: Jews appear as mice, Nazis as cats, Poles as pigs. Its style is influenced by the Expressionist everyman ‘wordless novels’ of Frans Masereel. The characters in Maus look almost the same, interchangeable, which has an empathetic effect – these were people just like you, it implies, who found themselves within a collective nightmare. The fact that Maus is a personal familial story underlines that this is not ancient history. The traumas are still unfolding, still exerting pressures upon survivors and their kin. The past is still very much there in the present.

There are many disturbing scenes, seen vividly in passing (‘they hanged there one full week… his wife ran screaming in the street’) yet it is an intensely domestic, interior, street and room-level book. It’s a loving heart-breaking portrait of a family afflicted by terror and tragedy, yet it’s told in a candid unsentimental way. Spiegelman’s father, a Holocaust survivor, has heroic qualities yet is infuriating; the book shows that damaged people cannot be expected to be saints. The author is riddled with self-doubt, worrying of inauthenticity and exploitation, often in meta-reflections upon the comic book itself. Its portrayal of the world in which the Holocaust took place is equally complex. People do what they can to survive. There are betrayals and allegiances, blind spots and hustles. The story of his parents’ lost son exemplifies the quandary. In an attempt to save him, they inadvertently send him to his death. The boy then becomes the overshadowing personification of all that is perfect in contrast to their surviving son’s natural imperfection. Spiegelman unties this endless knot, attempting to untangle himself. It is an astonishingly open-hearted confession.

Many cultures share the concept of the evil eye. It is known as ayin hara in Hebrew. Amulets like the hamsa and nazars are used the world over to protect against it. Maus has similar properties. The excoriating honesty of the book acts as a mirror, not just to Art Spiegelman but to the wider world. It deflects the malevolent gaze. And it is vital because it is troubling.

Too often, our cultural and political discourse has the quality of a roaming evil eye, searching for expedient controversy, for works to ban and people to banish, often under disingenuous claims of benevolence. All sides engage in this. Perhaps we simply need more stories, all the knowledge we can muster, rather than bemoaning censorship in one place and encouraging it elsewhere. Maus is a world in itself. We debase it and ourselves by wielding it as a blunt weapon or by erasing it entirely. Its lessons are delivered subtly and powerfully through the lives within it, which refuse to be abstracted. ‘It would take many books, my life,’ Spiegelman’s father says, ‘And no one wants any way to hear such stories.’ So much depends on proving him wrong.