Featuring Julien Creuzet, Christoph Büchel, Koo Jeong A, Paul B. Preciado; J.J. Charlesworth and Manuel Borja-Villel on Venice Biennale; reviews of Whitney Biennial, Thomas Hirschhorn, Matthew Wong and Vincent van Gogh; and much more

***Subscribe now or get your copy from our new online shop***

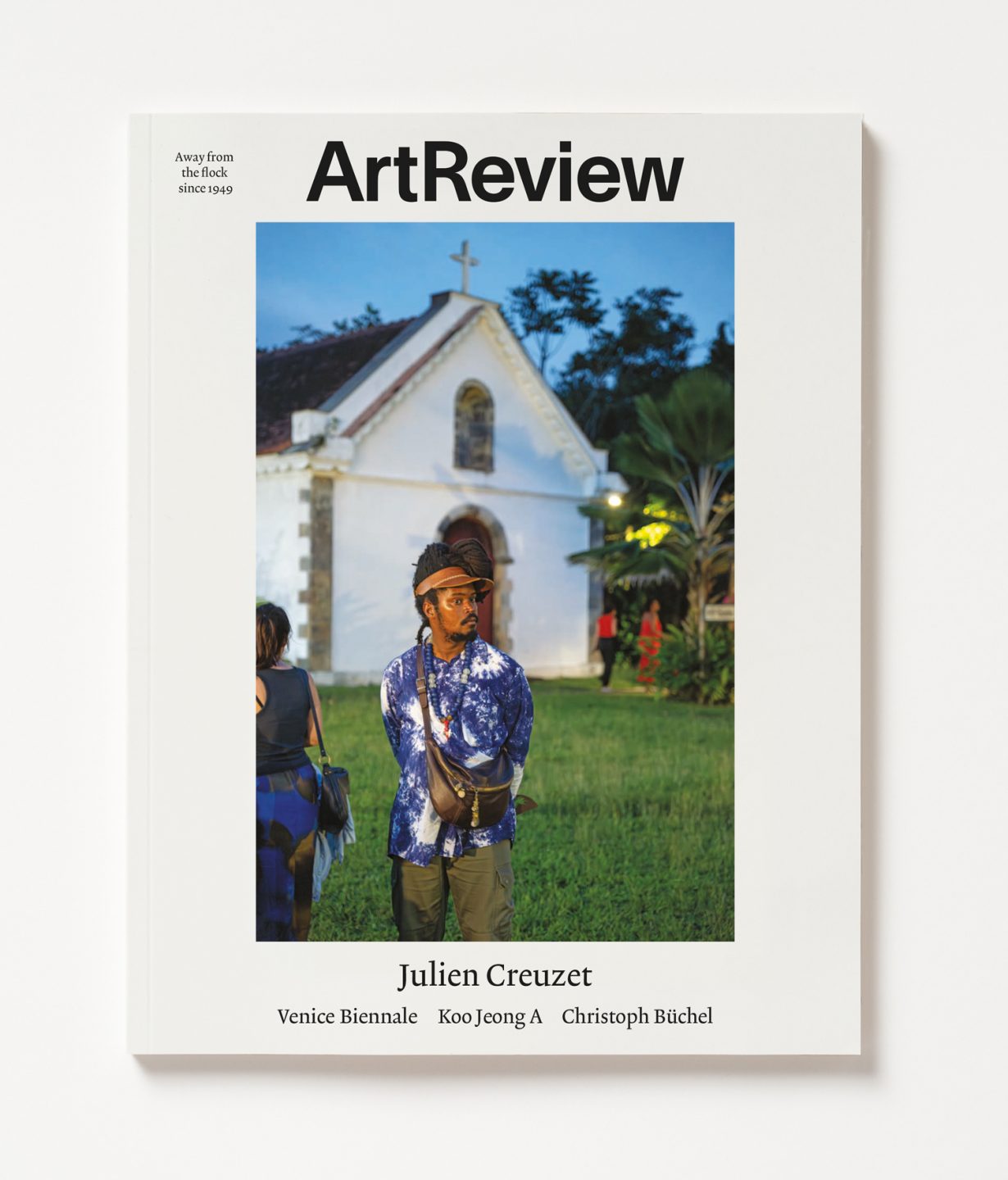

ArtReview’s April cover artist, Julien Creuzet, is representing France at this year’s Venice Biennale. Creuzet chose to launch his project for the pavilion in Martinique – where he grew up. Through poetry, film, sculpture and performance, the artist offers a version of France that reckons with its colonial history. Much of his practice is influenced by Négritude – an anticolonial movement founded in Paris in the 1930s by a group of African and Caribbean students – and the philosopher Édouard Glissant. ‘Creuzet’s practice is in complex dialogue with the work of those who came before him: the references are in how he handles poetry and music, and in his use of abstraction,’ writes Skye Arundhati Thomas. ‘There are also secrets in this work, not everything is immediately perceptible or translated for the viewer; it’s the right to opacité, as proposed by Glissant.’

Relationships between the tangible and intangible, and people and places, are also explored in the work of Koo Jeong A, who will be presenting ODORAMA CITIES at the Korean Pavilion. Known for their site-specific architectural spaces that centre ephemeral ‘materials’, including smell and sound, Koo put out an international open call for answers to the question, ‘What is your scent memory of Korea’. ‘When I was invited to propose a project for the Korean Pavilion, I was thinking of the need to talk about our time, which is a time of separation,’ Koo tells Andy St. Louis. ‘I think it’s important to think more about togetherness and about a common future. And since the Giardini in Venice is also divided into nations with the pavilions, with this project I wanted to provoke something that will create some transnational pavilion that proposes an alternative to this fragmented outlook.’

Meanwhile Stephanie Bailey looks at the work of the divisive Swiss artist and provocateur Christoph Büchel. His projects include turning a tenth-century church in Venice into a mosque for the 2015 Venice Biennale; The Mosque was promptly shuttered by the city’s authorities. He installed Barca Nostra in the Biennale’s 2019 edition, a controversial work that resurrected a ship that had sunk while carrying migrants between Libya and Lampedusa; the disaster resulted in more than 800 deaths. Büchel returns to Venice again with an exhibition at the Fondazione Prada, presenting Monte di Pietà: ‘A central element to the exhibition is The Diamond Maker: lab-grown single-carat diamonds that Büchel has been making since 2020, using his unsold works and DNA from his own faeces, with the intention to continue until he dies,’ writes Bailey. ‘Entangling his apparent loathing of Western imperialism with his contempt for the mainstream artworld and his role within it, Büchel is fine with playing the villain in order to maximise the scope of public discussion around his provocations.’

Reflecting on Adriano Pedrosa’s theme for this year’s edition of the Venice Biennale, Foreigners Everywhere, J.J. Charlesworth questions what’s next for the contemporary art biennial, now that the era of neoliberal globalisation that shaped it has started to unravel. The Biennale is perceived as a ‘permanent and immoveable presence in the global art system’, but Charlesworth notes that ‘it has never been immune to pressures for change or contemporary politics, or, at its most radical, to the possibility of disappearing altogether’, citing the delayed ‘Biennale of Dissent’ among several editions during the mid-1970s that did away with national pavilions. ‘The tensions emerging in world politics are starting to fracture the benign, if vacuous internationalism that has underwritten’ these international art events.

Looking back through 75 years of its archive, ArtReview considers ‘some of the shifts across three decades, during which the Biennale went from Modernism to postmodernism, and from a Eurocentric institution to a more global one, via the political and cultural crises of the late 1960s and 1970s’. A selection of republished articles from across the decades are updated with annotations by ArtReview’s current editors.

Also in this issue

Benoît Loiseau interviews philosopher Paul B. Preciado about the making of his new feature film, Orlando, based on Virginia Woolf’s novel of the same title; art-historian and curator Manuel Borja-Villel asks whether it’s possible to decolonise a biennial; Deepa Bhasthi looks at how, in India, true-crime documentaries are deployed to reinforce patriarchal fantasies; Cassie Packard considers art’s role in creating and recycling e-waste; and Adam Thirlwell asks what aesthetic strategies can make sense of an unstable present. Plus reviews from around the world, including the Whitney Biennial in New York, Shanshui: Echoes and Signals at M+, Hong Kong, and Jonathan Jones at the newly refurbished Artspace, Sydney. As well as books about NFTs, Tipu’s Tiger and Tschabalala Self.

Plus

Included with ArtReview’s April issue is a special publication dedicated to Brazil, produced with the support of Instituto Guimarães Rosa. Inside: Curator Raphael Fonseca meets the artist communities beyond São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro; six artists describe how their home cities – from the colonial-era coastal town of São Luís, Maranhão, to Belém at the mouth of the Amazon River – have inspired their work; five artists point readers in the direction of fellow artists who have not yet garnered the attention they deserve. Plus interviews, artist projects and a guide on where to see the best of Brazilian art, both at home and abroad, and not least at the Venice Biennale.

***Subscribe now or get your copy from our new online shop***