In a time of lockdowns and quarantines, artists are looking for ways to capture the immaterial

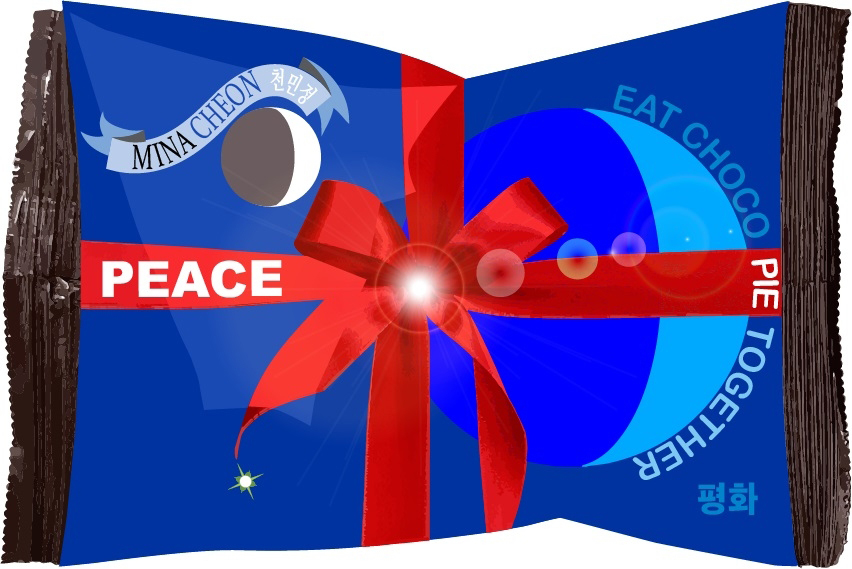

Mina Cheon’s virtual chocopie for the digital Eat Chocopie Together initiative, 2020. Courtesy the artist and Asia Society Triennial

One of the many things that ArtReview Asia learned during lockdown was what a chocopie is. It’s two layers of cake sandwiching marsh- mallow and covered in chocolate. Sounds disgusting. But, as with many things right now, ArtReview Asia has never tried one IRL so it can’t say for sure. (But it knows.) It has ‘sent’ a virtual one to a friend however, via Mina Cheon’s online artwork Eat Chocopie Together (at EatChocopieTogether.com), which is the opening gambit of October’s inaugural Asia Society Triennial titled We Do Not Dream Alone (Asia Society Museum New York, and various venues, 27 October – 27 June). Launched on Korean Liberation Day (15 August, commemorating the peninsula’s liberation from Japan) the project benefits the Korean American Community Foundation’s COVID-19 Community Action Fund. Two dollars are raised (thanks to an anonymous benefactor) when you select a cake and send it to someone and another when it is (virtually) eaten by the recipient. Chocopies (an early-twentieth-century American ‘snack’ that was exported to South Korea during the 1970s, where it became an enduring hit) became a symbol of crossborder solidarity in Korea in 2013, when South Korean workers at the jointly managed Kaesong Industrial Complex gave them to their North Korean counterparts, starting a craze. The virtual installation is based on Cheon’s real installation of real chocopies that visitors were invited to (really) eat at the 2018 Busan Biennale. All of which (the real to virtual, enigmatic fundraising initiatives, etc) makes you wonder if art is sometimes merely an excuse for doing things in a roundabout way. Or perhaps this virtual edition is simply a way of fuelling your hunger for the real thing – whether that’s real installations, real chocopies or a real feeling of friendship and solidarity in these atomised times.

The ‘real’ triennial, curated by artistic director Boon Hui Tan and associate director Michelle Yun, will take place at the Asia Society Museum and various venues around New York, and aims at promoting discourses surrounding Asian art and culture in the heart of America’s famously myopic artscene. The title is borrowed from Yoko Ono’s 1964 publication Grapefruit and artists include ArtRevew favourites, kimsooja, Song-Ming Ang, Dinh Q. Lê, Prabhavathi Meppayil, Hetain Patel, Melati Suryodarmo, Xu Zhen® and many others whose work ArtReview Asia will doubtless learn to favour once it – errr – actually tucks in.

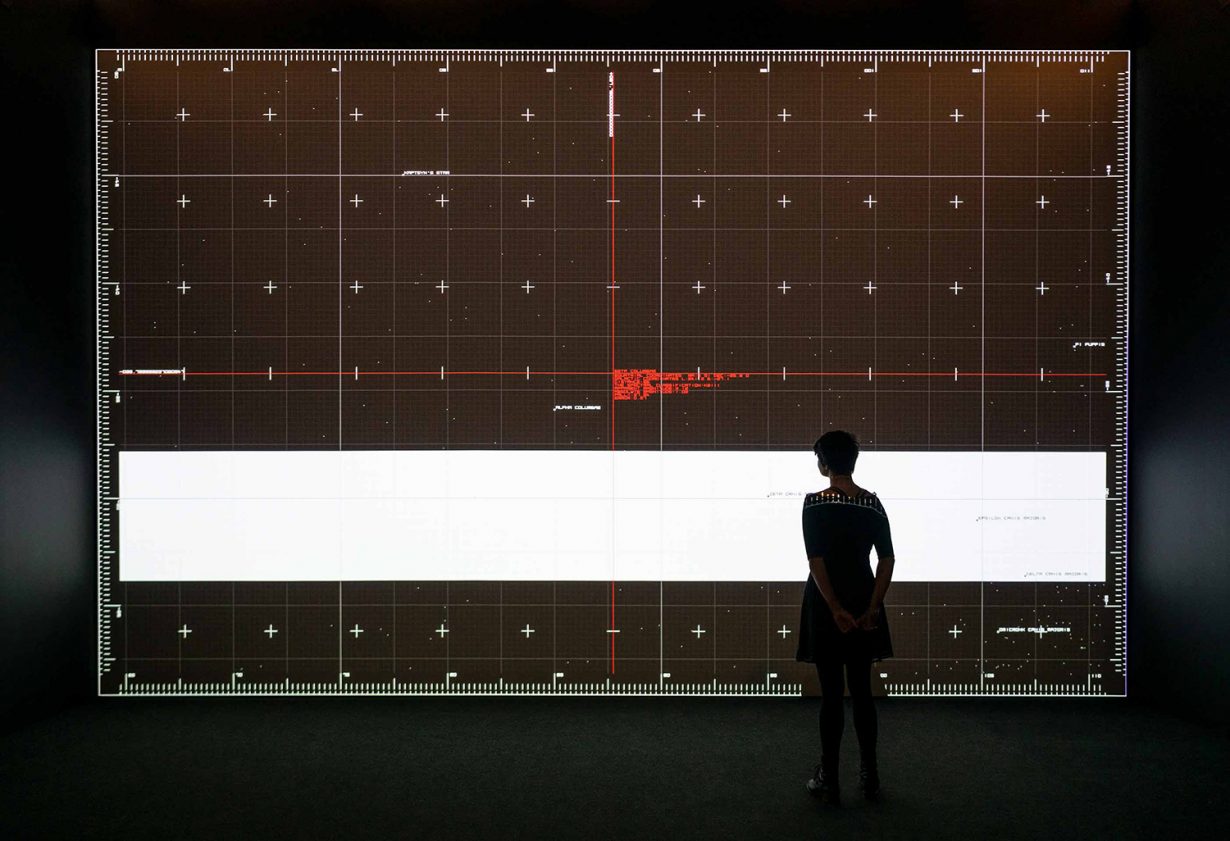

Despite the mainstream artworld’s relative slowness to embrace it, the turn to digital art (or the use of the computer as a primary tool for creating art) is, of course, far from a new phenomenon (not everything was invented in the age of the virus) and UCCA Beijing’s upcoming exhibition Immaterial/Re-material: A Brief History of Computing Art (through 17 January) sets out to remind us of its history. Beginning in Europe during the 1960s, when artists such as German Manfred Mohr switched from Abstract Expressionism-type paintings to representing computer-generated geometries, the exhibition, which features work by 30 artists goes through to Japanese musician Ryoji Ikeda’s experiments in giving form to big data and China’s own aajiao’s investigations of social media and digital information filters. Alongside nods to some of the pressing issues of our current times, the exhibition also references (in its title) Les Immatériaux, philosopher Jean-François Lyotard’s landmark 1985 exhibition at the Pompidou Centre (cocurated with design theorist Thierry Chaput), which the Frenchman (best known as a theorist of postmodernity) described as ‘a kind of dramaturgy placed between the completion of a period and the anxiety for an emerging era’; a show which foregrounded new material sensibilities heralded by the advent of globalism and related developments in new media and technology, and proved an inspiration to artists such as Pierre Huyghe and Philippe Parreno. High standards then for UCCA to match.

The move away from traditional material culture is also in evidence at TANK Shanghai, although the inspiration for the title More, More, More (through 31 January) comes from a 1970s disco song by The Andrea True Connection rather than French postmodern philosophy. Still, perhaps, as this show curated by the Guggenheim Museum’s X Zhu-Nowell and musicologist Frederick Nowell (who distance themselves from their own materiality by practicing under the name Passing Fancy) demonstrates, the links between the two are not so stretched as you might think. Works by 28 international and local artists incorporate materials such as perfume, music, bacteria and digital machine-readable formats, alongside poetry, figurative painting, ink painting and line drawing in a show that’s designed to engage all the senses and operate, one presumes, in a continual flux of dis- and re-embodiment. Among the artists whose work is on show are Sophia Al-Maria (fresh from screenwriting the Sky Atlantic series Little Birds), Ho Chi Minh City-based collective Art Labor, Foshan-based duo Mountain River Jump! (whose work also features in the Asia Society Triennial), Swiss sculptor Claudia Comte, Berlin-based Jesse Darling (whose work, in a variety of media, focuses precisely on what it means to be a body in the world), Laure Prouvost (whose film installation in the French Pavilion was one of the standout works of the 2019 Venice Biennale) and cult Chilean artist, poet and activist Cecilia Vicuña.

Also exploring the current turn away from materiality (it’s only natural in a world in which bodies are not travelling, materials are not shipping, borders are closing and ideologies clashing) is the Hara Contemporary Art Museum’s group exhibition Time Flows: Reflections by 5 Artists (Tokyo, through 11 January). Although here the emphasis is largely on attempts to capture the immaterial in material form. The five in question are photographers Tomoki Imai, Tamotsu Kido and Tokihiro Sato, animator Masaharu Sato and mixed media artist Lee Kit. Lee’s Flowers (2018, and in the Hara collection) is an installation of projected light into the darkened gallery spaces; Sato presents work from his Photo-Respiration series (2020), comprising long-exposure photographs of landscape scenes that capture the movement of handheld penlights or mirrors. Imai’s Semicircle Law series (2013–) comprises photographs taken from peaks within a 30km radius of the failed Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant shot in the direction of the doomed plant. While the late Masaharu Sato (who died last year) used animation and live footage in Tokyo Trace (2015–16, also in the Hara Collection) to contrast the dreams and reality of the Japanese capital as it prepared to host the 2020 Olympic Games, now scheduled to take place in 2021. Time flows indeed.

Which is why, perhaps, it’s much easier to chase past time than anything in the elusive present or illusional future. This is precisely what the Power Station of Art (PSA) in Shanghai is doing with Shanghai Waves: Historical Archives and Works of the Shanghai Biennale (through 15 November), an exhibition that looks back at the history of mainland China’s first biennial of international contemporary art (founded in 1996) in preparation for the launch of the now postponed 2020 edition, titled Bodies of Water and curated by architect Andrés Jaque. (It will now take place in phases beginning on 10 November and running through until 27 June.) Particularly poignant then, among the more than 60 artworks (created by 51 international and domestic artists or groups) on show is Xu Zhen’s Dang, Dang, Dang, Dang… (created for the 2004 biennial), a replica of the clock from what was then the China Art Museum (which formally hosted the biannual event and is now the Shanghai History Museum) whose hands run 60 times faster than normal. The exhibition as a whole provides an overview of changing tastes and interests in art over the last quarter century as well as a lens through which to view how the city has evolved (rapidly) during that time. Alongside works by Chen Zhen, Willem de Rooij, Ding Yi, Gu Wenda, Liu Wei, Raqs Media Collective, Zhang Enli, Zhang Huan, Zhou Tiehai – effectively the great and the good of the artworld today – the exhibition also includes their reminiscences of past biennials, postcards, letters and books to create a document that is as much personal as it is artistic.

Not that ArtReview Asia’s a total fatalist. Over at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, Between Earth and the Sky (through 18 October) is a group exhibition that focuses on immersive art experiences that complicate the relationship between artist and viewer, performer and spectator. The general aim is that by the time you come out of the show you might not be too certain which is which. Hopefully that means you’ll have gained some agency even if you don’t actually know it. Or have it.

Here durians – a proper snack – replace chocopies in the form of Durian Pharmaceutical (2020) a product of Yu Cheng-Ta’s alter ego FAMEME, a Taiwanese farmer-turned-internet- celebrity-turned-influencer, who having proclaimed the magical properties of the infamously odoriferous (but delicious) fruit in the US (at Performa 19) and South Korea (at the Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, where earlier this year he introduced the Durian Exercise Room), is now moving into the pharmaceutical industry by launching the Durian Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd to exploit and promote (same thing really) the healing properties of the durian extract Misohthornii (MST). Which will doubtless shortly be on Donald Trump’s list of miracle ‘cures’ for COVID-19. He’s probably got shares in Baboo’s topical Corona Villa (2020), an ‘anti- epidemic hotel’ (installed in the museum) offering services such as virtual lovers, singalongs, collective sketching and valet shopping – yeah, ArtReview Asia knows: you might as well stay at home. But life is always better in a gallery, where you can be a viewer not a victim… oh… In any case, you’d be missing out on Liang-Hsuan Chen & Musquiqui Chihying’s The Gesture II (2020), which explores a history of hand gestures from Hong Kong zombie movies of the 1990s (for more on which you’ll want to have checked out the summer issue of ARA) through to expressions of hygiene and communication in our masked-up COVID-19 era. What? You might as well stay… Oh. Well, you’d be missing out on dance performances choreographed by Chen-Wei Lee and meditations on the novel by Ching-Yueh Roan too. You should really get out more (as long as it’s safe to do so).

Not getting out is, in part, the subject of Shirazeh Houshiary: As Time Stood Still, at Lisson Gallery (Shanghai, through 24 October), which is, ironically, given that subject matter, the British-based Iranian artist’s exhibition in Shanghai. Five new paintings and a sculpture are on show, all inspired by the artist’s period of virus-containing lockdown in the UK, and her increasing awareness of natural beauty during the period. A Turner Prize nominee back in 1994, Houshiary was awarded the Asia Society’s ‘Game Changer Award’ in 2018. Appropriately then, her abstract, maplike works in this show aim at capturing change and movement via the effects of light and atmosphere, and patterns that look at once like fingerprints, weather maps and particle flows. Alongside these, her sculpture Duet (2020) was partly inspired by the ribbon motifs she encountered during a visit to the Mogao Grottos in Dunhuang and their repositories of early Buddhist art.

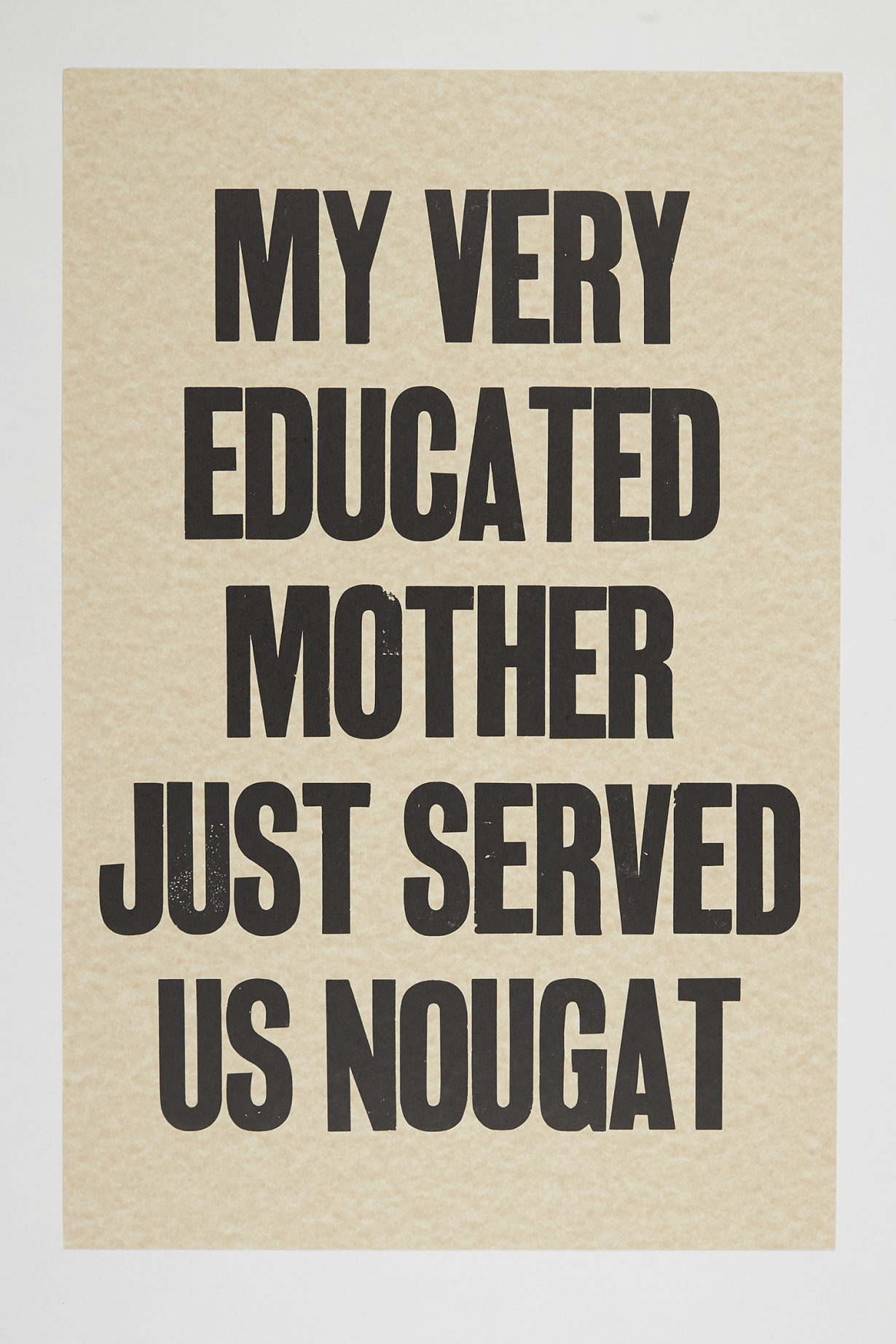

French-Moroccan artist Yto Barrada improbably addresses themes of architecture, urban transformation, botany, geology, experimental education, and home economics in My Very Educated Mother Just Served Us Nougat, her curiously titled solo exhibition at Mathaf in Doha (through 30 November). Barrada approaches these subjects through the life stories of five women: her own mother (who was instrumental in establishing a Montessori school in Morocco); ethnographer Thérèse Rivière; and artists Bettina, Saloua Raouda Choucair and Lourdes Castro. The works on show are derived from bathroom fittings, educational toys, maps, mnemonic phrases, wallpaper and, of course, pieces of nougat (here the material for a series of sculptures), and explore received and acquired learning, plurality and authenticity. While also mixing their seriousness with a healthy dose of humour and fun. (Both of which seem in somewhat short supply across Asia’s artscenes this autumn.)

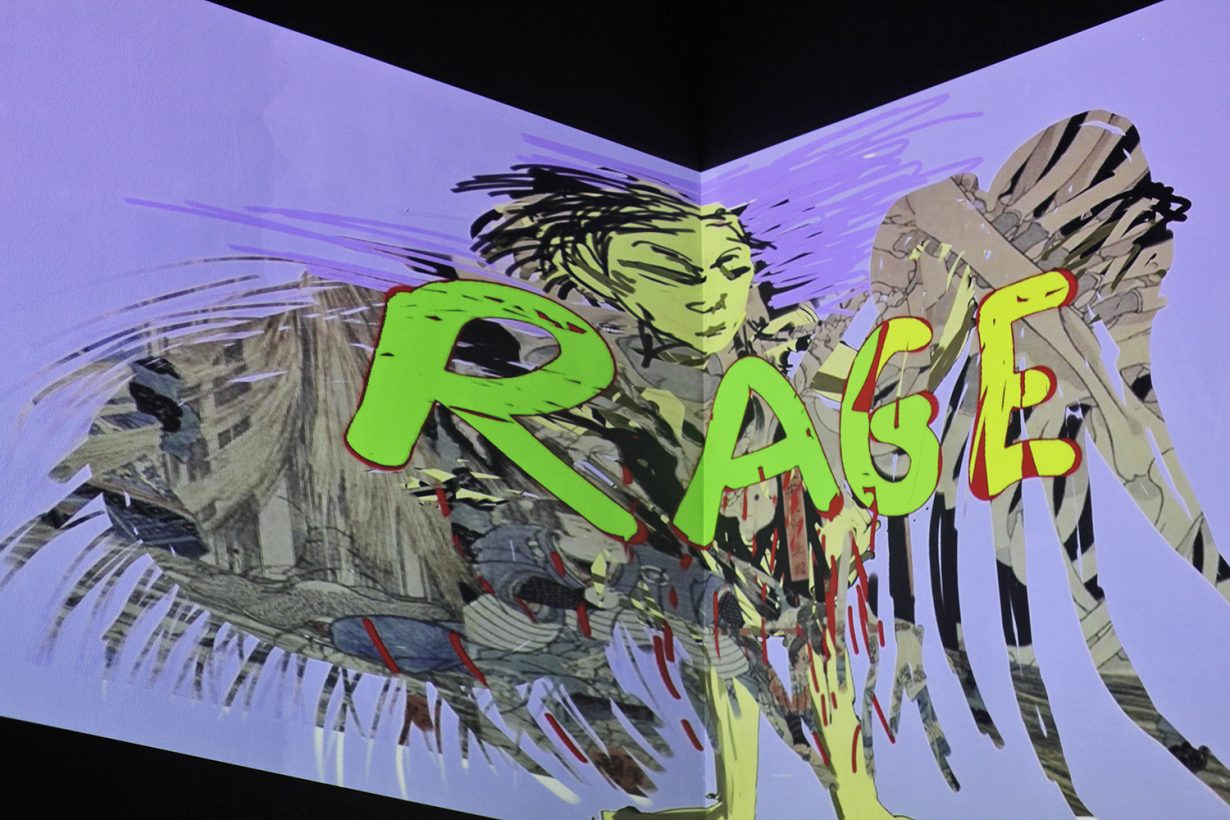

Over in London, Nalini Malani, one of the pioneers of film, video art and performance (sometimes all at once) in Indian contemporary art, and generally one of the most interesting artists working right now (whose 2017 retrospective at the Pompidou Centre in Paris was cheerily titled The Rebellion of the Dead), also incorporates the lives of others into her new commission Can You Hear Me? (Whitechapel Gallery, through 6 June). The installation, in what used to be the reading room of the Whitechapel Public Library, takes the form of 84 projections featuring hand-drawn images and notes and quotes paying homage to an array of writers including Hannah Arendt, James Baldwin, Bertolt Brecht, Veena Das, Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Milan Kundera, George Orwell and Wislawa Szymborska.

Back in Thailand, the Bangkok Biennial (through December) (not to be confused with the Bangkok Art Biennale) has restructured itself for its second iteration in the wake of the current pandemic. The event, which has no overall directors or curators, functions as a series of pavilions proposed on an open-call basis in an attempt to decentralise conventional art practice, encourage diversity, and move away from received wisdom and top-down curatorial models. The 2018 edition gathered 200 artists from 26 countries in just under 70 pavilions. Reviewing it, ArtReview Asia Contributing Editor Max Crosbie-Jones noted that its opening ceremony alone seemed ‘a world away from the billowing curator-speak, arse-kissing of headline sponsors and other stale formalities that normally mark the opening of a commercially underwritten art event’. This time the unruly event, which back then drew together many of the marginal factions within Thailand’s diverse art scene, will take place in three phases, starting at the end of October and lasting the course of a year. Still time, then, to get your proposals for a pavilion in.

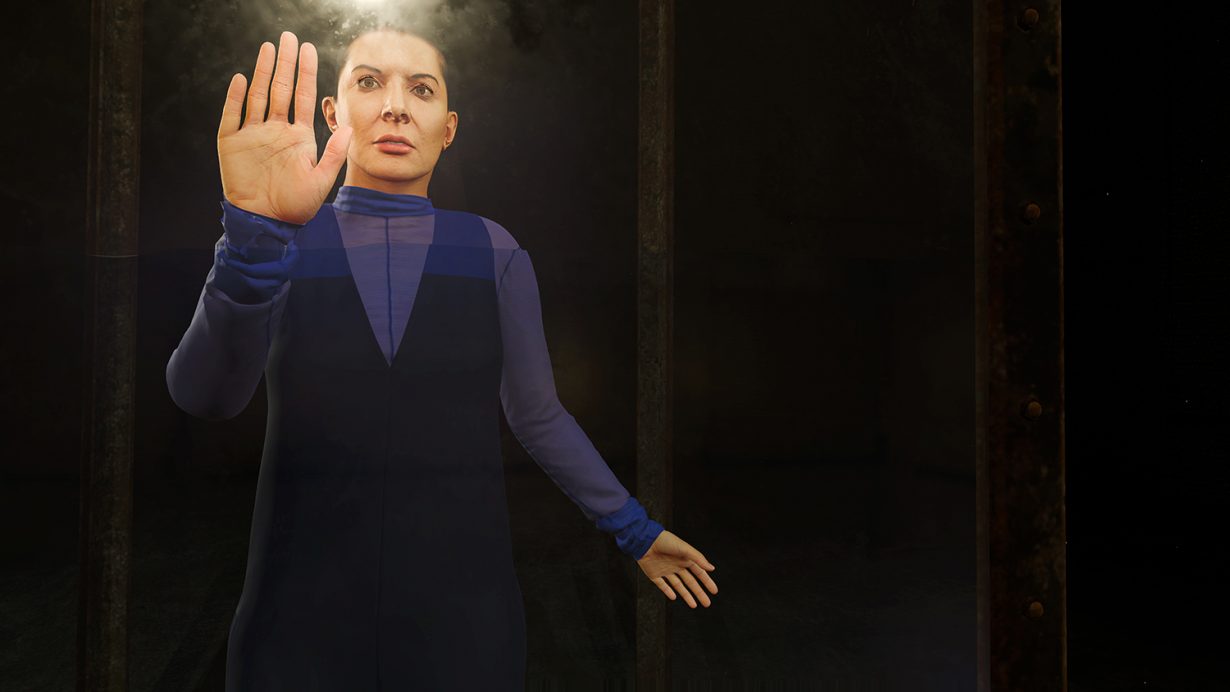

At the opposite end of the spectrum, where (presumably) some arses are kissed and curators are allowed to speak, the Bangkok Art Biennale (not to be confused with the Bangkok Biennial) is also launching its second edition this October. Titled Escape Routes (29 October – 31 January) and starting from the premise that ‘our dream of utopia is running on empty. The fantasy paradise in the Land of Plenty where wine, milk and honey flowed as people partied, sunbathed and slept around, an escape from earthly suffering, has turned bitter and sour’. And that was written by artistic director Apinan Poshyanada and his curatorial team before the eruption of COVID-19. In any case, however miserable the pre-COVID-19 era had become, there’s no doubt that Escape Routes has added relevance now, as, probably, does its optimistic pledge to offer ways out of the current calamity. And the calamity before the current one. Among those artists providing the exits are Marina Abramović, Anish Kapoor, Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook, Christian Jankowski, Yoko Ono, Dinh Q. Lê, Reena Saini Kallat and Rirkrit Tiravanija. While venues include the Wat Arun and Wat Phra Chetuphon temples. Remember the lesson from Manit: it’s about ideas not individuals. Unless you have to kiss their arses. Which you shouldn’t. In these sanitised times.

Los Angeles-based artist Marnie Weber is taking part in Asia’s other autumn biennial, in Busan, South Korea. In the meantime an exhibition of her work goes up at Simon Lee, Hong Kong (through 31 October). While the Busan Biennale will feature an installation centred around a new film, Song of the Sea Witch (2020), which focuses on a mysterious sea witch who is threatened by a flock of angry birds, the show at Simon Lee focuses on a series of collages that expand that folkloric realm. Girls with the faces of owls recline eerily amidst the clouds, clowns cavort around a dilapidated barn like an at times nightmarish, at times cutesy fairy-tale world of the subconscious.

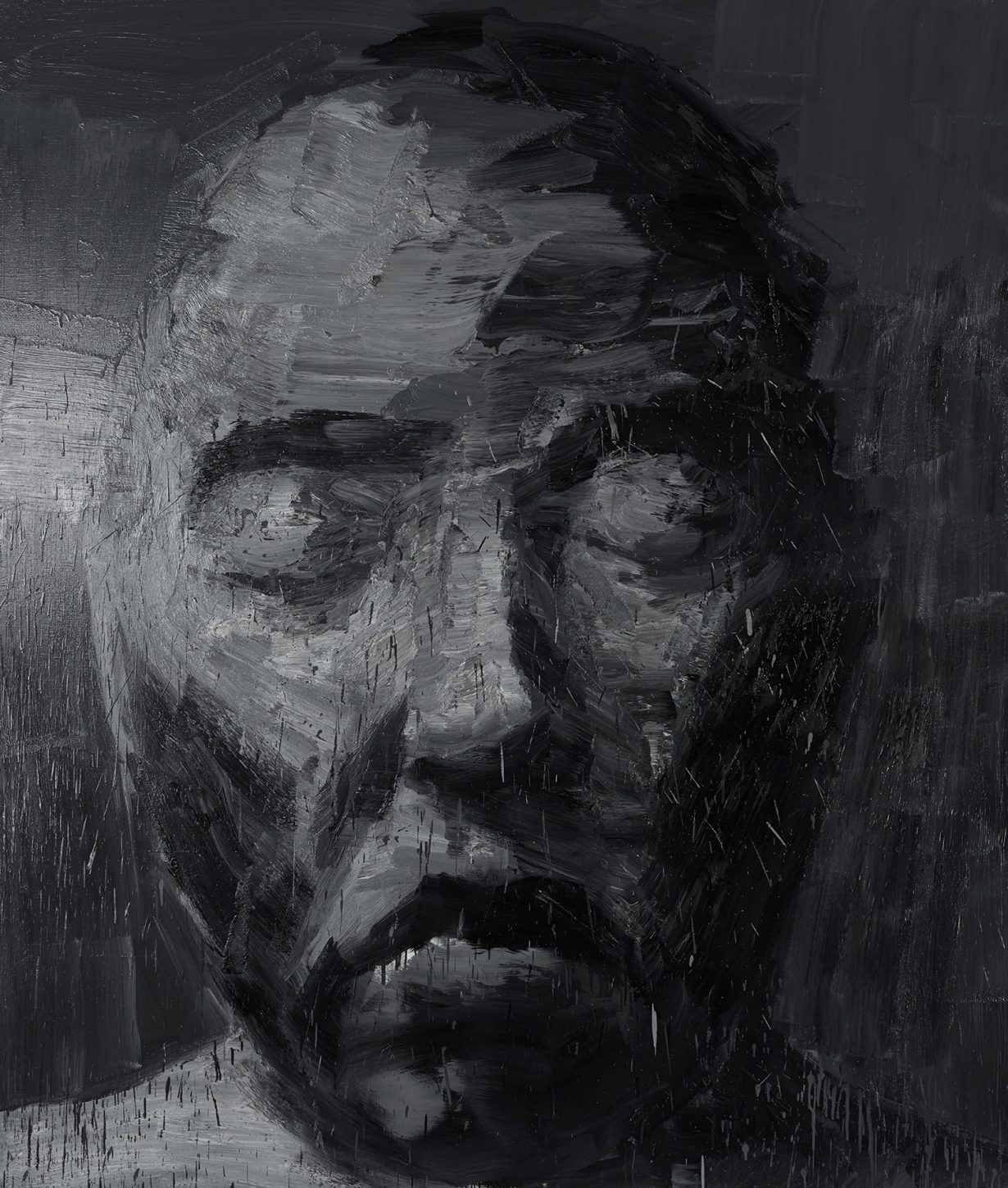

There’s a surreal quality too in the work of two of Europe’s most influential living artists, painter Michaël Borremans and sculptor Mark Manders, who exhibit together at the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa. In Double Silence (through 28 February), their works unpick the language of their respective mediums to operate in a dialogue that spins through the materiality of the human body and its representations or transfigurations through pasts, presents and futures. Which, presumably, is the, um, ‘sound’ of silence. The whole thing, of course, will be laced with irony. Particularly now that we’re being educated to think that other people’s bodies are little more than walking plague pits.

September saw the delayed opening (originally scheduled to open in May) of Zhang Huan’s largescale solo exhibition at The State Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg (through 8 November). The thirty works on show include examples of the artist’s celebrated ‘ash paintings’ (created using the ash from incense burned in Buddhist temples), a series of new works created in response to the Hermitage collection and his new Love series of paintings created during lockdown in China as a way of preserving the memory of those who died as a result of the pandemic. Painted in red on white canvas (and evolved from the artist’s Reincarnation series), the images look like a series of giant, torn-out hearts.

At this stage you might need to look at something of a more curative nature. And that’s certainly an aspect of the work of Chen Zhen, of whose installations from the last ten years of his life (he died of cancer in 2000, aged forty-five, having been diagnosed with autoimmune hemolytic anaemia aged twenty-five and given five years to live), are on show in Short-circuits at the Pirelli HangarBicocca in Milan (through 21 February). ‘As an artist,’ Chen once stated, ‘my dream is to become a doctor. Making art is all about looking at oneself, examining oneself and somehow seeing the world.’ Jue Chang, Dancing Body – Drumming Mind (The Last Song) (2000) is an installation of chairs and beds gathered from around the world and covered in cow hide and suspended from frames to create an improvised drum set in a manner reminiscent of a Chinese bianzhong. The work is activated by performers who use their bodies to beat the drums in motions reminiscent of traditional Chinese massage techniques. An earlier version of the work from 1998 featured chanting Tibetan monks (praying for peace). Also on show is Jardin-Lavoir (2000; having grown up in Shanghai, the artist moved to Paris in 1986), a series of 11 beds transformed into basins and filled with continually flowing water that ‘purifies’ everyday objects, such as clothes and books. That’s the new normal for you and me.