Featuring a series of coverage on care in the artworld; Rirkrit Tiravanija, Mike Kelley, Emilie L. Gossiaux and Rory Pigrim; columns on Islamophobic violence, translation and The Bear; and much more

Back in the old days, ArtReview used to go to museums and galleries for entertainment, for fun. How it would laugh when it saw Picasso’s latest smudgy portraits at a Cork Street gallery, or Yoko Ono’s unfinished paintings over at the ‘groovy’ space in Mason’s Yard. Art galleries used to be just for aesthetic delectation. Now they’re increasingly repurposed as sites of care. Literally in some cases, during the recent pandemic: Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall opened as a pop-up vaccine spot, as did the cavernous Pirelli Hangar Bicocca in Milan. Imagine being vaccinated in the middle of Anselm Kiefer’s Seven Heavenly Palaces (2004–15), with its towering concrete impersonations of corrugated iron shacks stacked one atop the other. Some people are probably still haunted by it. But what’s more likely lurking over your shoulder at a gallery these days is an installation providing some kind of instruction or access to the sorts of things that healthcare providers, psychologists and social workers used to do. Sometimes ArtReview wonders if art is the glue in the social contract – the one by which people willingly come together to thrash out a collective will or a state – binding the whole thing together when it’s falling apart.

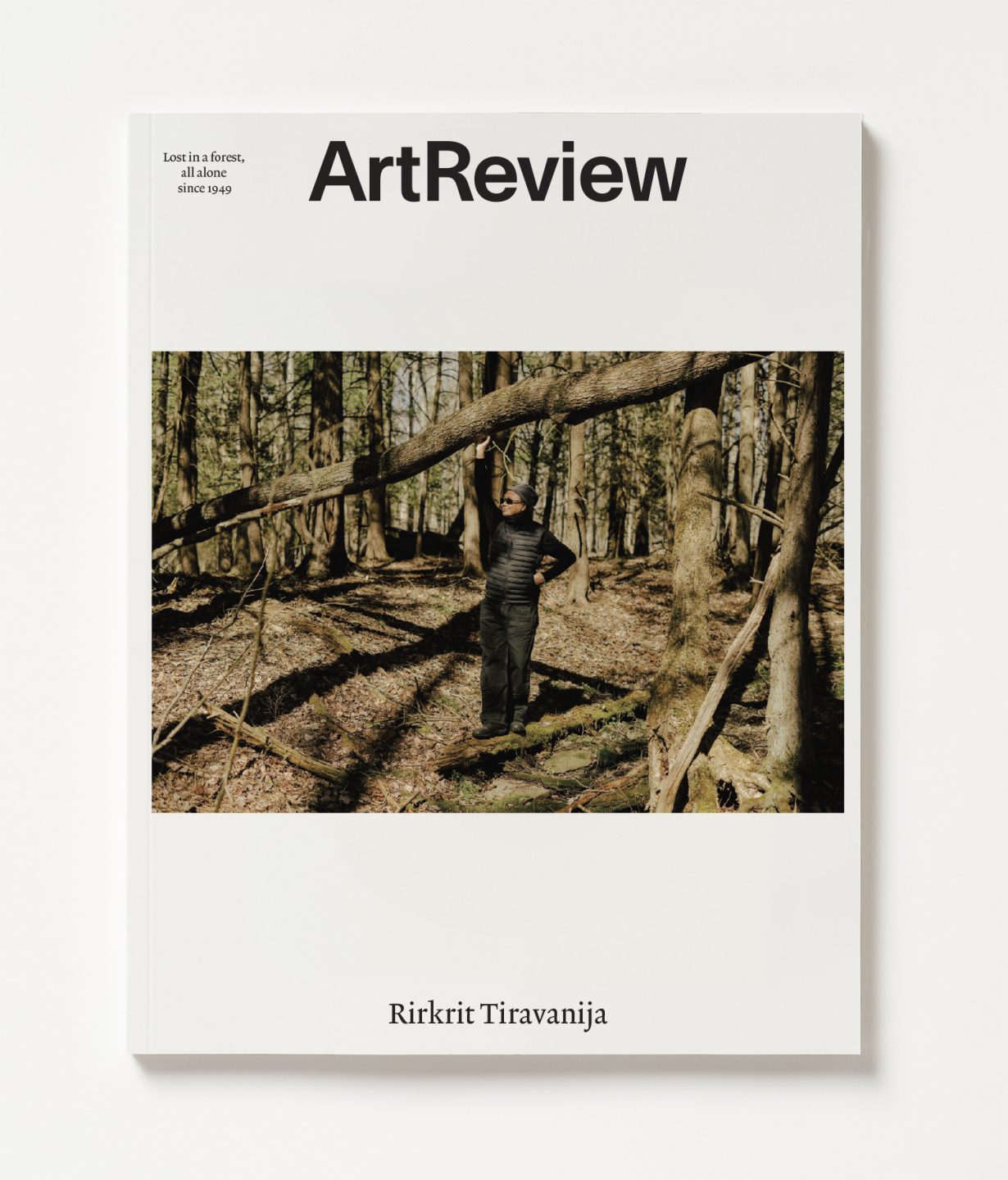

Rirkrit Tiravanija’s unique way of working emerged at a moment when society was becoming unstuck around him. He started his ‘relational’ cooking projects – inviting the public into art spaces to eat the pad thai he cooks, and then to rest on the straw mats and foam mattresses he provides – in New York City and Cologne during the economic fallout of the 1990s, when unemployment almost doubled in those two cities. His art, Jessica Lanay writes in her profile of the artist, provides not just the ‘dignities of living’ but a critique of why they were absent in the first place (a social contract unglued, if you like).

If Tiravanija offers solace to the body, and specifically the stomach, for decades the late Mike Kelley acted something like America’s therapist, ever ready with a wry critique of the country’s creaking mental state. Chris Fite-Wassilak notes in his profile that ‘Kelley seemingly treated every aspect of American culture, from school plays to discarded toys, as evidence of repressed memory syndrome’.

This question of art’s role in wellbeing comes up in the work of Rory Pilgrim, who has been nominated for the 2023 Turner Prize. Marv Recinto considers Pilgrim’s burgeoning career, alongside that of an earlier nominee for the prize, Helen Cammock. Both artists have lived with the bureaucracy of the British care system, and while pointed in its critique, their work also beckons to the extensive network of individuals who come together to make it function.

Nor is care necessarily provided by humans: Emily McDermott meets Emilie L. Gossiaux, an artist who, since losing her eyesight in an accident, has relied on her dog, named London, to guide her, and in the process London has become something of a muse. There are few who would argue that art can entirely replace proper, well-funded health and social care, and certainly John Quin, for many years a physician with Britain’s National Health Service, is not one of them; he does argue however that art can be a useful tool for the medical profession, both in aiding communication with patients and in diagnostic training. In a unique take, Dr Quin takes us through a few of the artworks that he has found as useful at his stethoscope.

Also in this issue

Deepa Bhasthi considers the hideous cycle of Islamophobic violence that dominates Narendra Modi’s India; Amber Husain ask if culinary TV series The Bear is a success because it stimulates our hibernating palates or whether we are enjoying little more than our just desserts; Jamie Sutcliffe shines a light on the tortuous labour inherent in cartoon-making; and the novelist Adam Thirlwell considers how questions of translation differ in visual art and in literature.

Plus

Oliver Basciano reviews the Bienal de São Paulo, finding a ‘show constructed on the scorched earth that colonialism left in its wake’; Claudia Ross asks what Ugly Painting in New York really is; Digby Warde-Aldam comes face-to-face with the work of Neo Rauch in Montpellier; and artist Athanasios Argianas catches a retrospective of avant-garde composer Iannis Xenakis in Athens.