In a new series responding to the temporary closure of physical galleries and museums internationally, published each Wednesday, ArtReview turns its critical eye to art hosted online. You might be starved of social contact, but you won’t be starved of art.

There was a time when the majority of online viewing pages hosted by art galleries were only open to collectors, a kind of digital VIP room that us mortals weren’t to sully with our virtual presence. Since the closure of their physical spaces however, the blue-chip players have used this existing infrastructure to stage ‘exhibitions’. Some of them – notably David Zwirner Gallery – are even opening up their spaces to colleagues. Others, of course, are rapidly building theirs. It is hard of course to retain the mystique of the gallery – a shop that does its level best to come across as anything other than a shop – when the necessary ‘buy now’ buttons remain in place (though of course they are often tastefully labelled ‘enquire’ or coyly ‘available’). Pace has these attached to each of the works in its online exhibition of Saul Steinberg (and, let’s be clear, no one is begrudging anyone making a living under the current circumstances, when culture, alongside, well, everything, is under threat), but the show otherwise comes with all the bells and whistles of an institutional survey (albeit on a truncated scale): there’s an independent curator (the art historian Michaela Mohrmann), contextualising blurbs, quotes from the artist and atmospheric archive photographs of Steinberg at work.

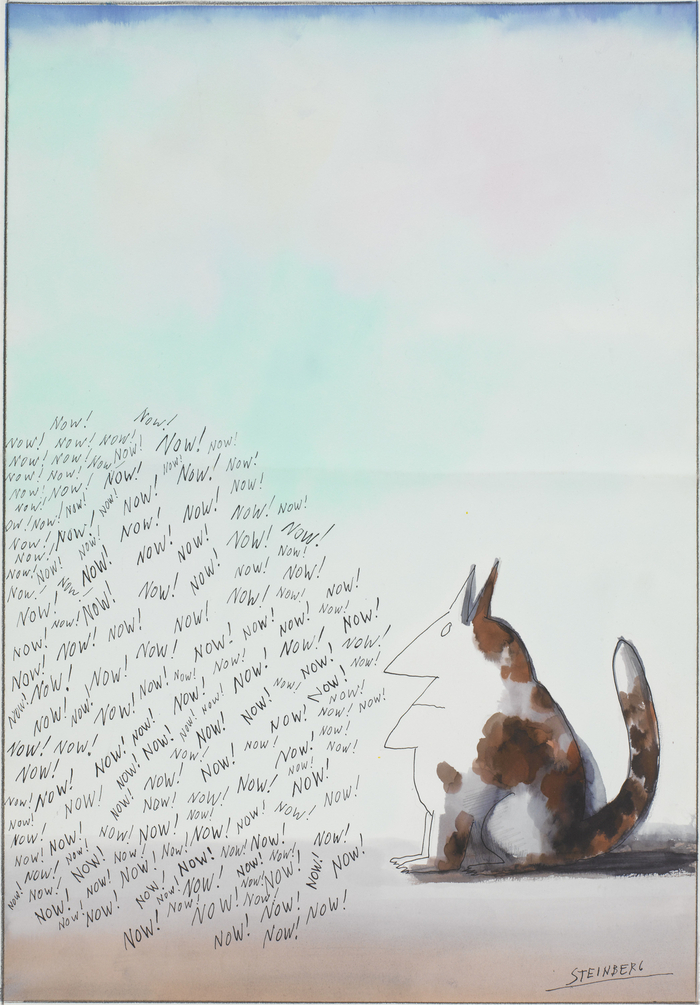

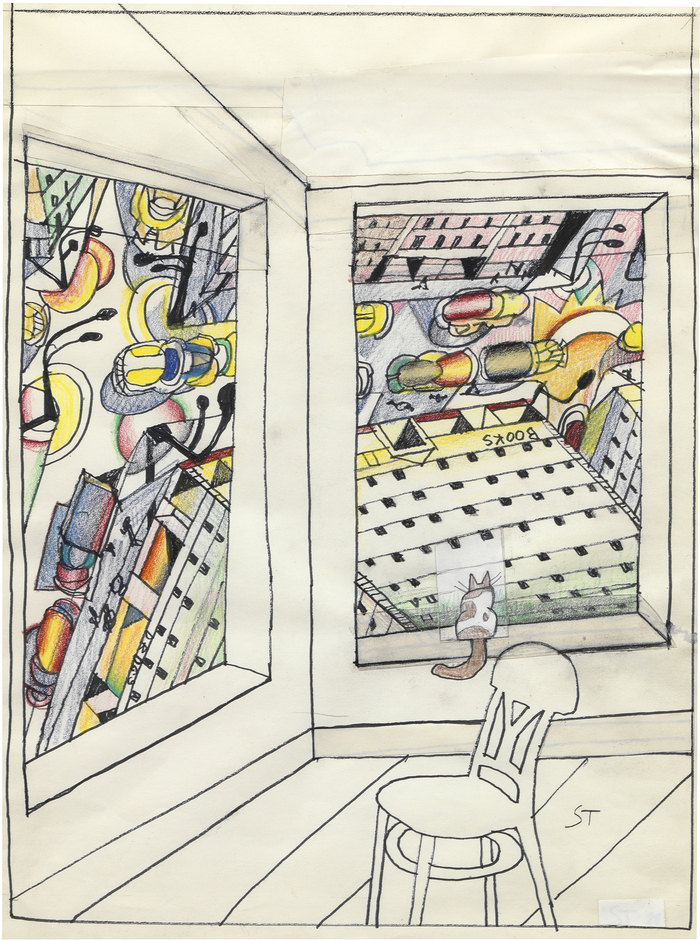

The show is titled Imagined Interiors, and we see Steinberg’s illustrations (Romanian-born to a Jewish family, the American artist was best known for his work in The New Yorker) depicting domestic scenes that range from the whimsical to the darker and claustrophobic. Fitting the theme of our times, the ‘interiors’ referred to in the title are not just architectural but psychological too. Untitled (Now!), made at some point in the early 1960s, a watercolour, pen and ink, graphite and coloured pencil composition on paper, shows an anthropomorphised cat staring into a cacophonous word cloud, each word screaming NOW! The cat ‘evokes the insularity of urban apartment-dwelling’ writes Mohrmann and it was indeed a recurring presence in the artist’s oeuvre, often anthropomorphised, sometimes presented just as a household companion. In Looking Down (1988) a cat stares out of one of two windows in a room unfurnished but for a single chair. Outside, a chaotic scene, the angles jumbled and perspective off-kilter, is in view. Such is the visual confusion of the composition (which takes inspiration from an eighteenth-century ukiyo-e print by Utagawa Hiroshige depicting an Edo-period brothel, also on view in the ‘show’), the windows might just as easily be paintings. But that’s when you begin to get lost in the maze of what’s real and what’s not. Even if these scenes are imagined, are they still that when put down on paper? Are they any less real than a drawing of an ‘actual’ interior? Do we expect anything in a drawing not to be imagined? After all, we have to use some degree of imagination to convert these 2-D representations into 3-D spaces. Worlds within worlds…

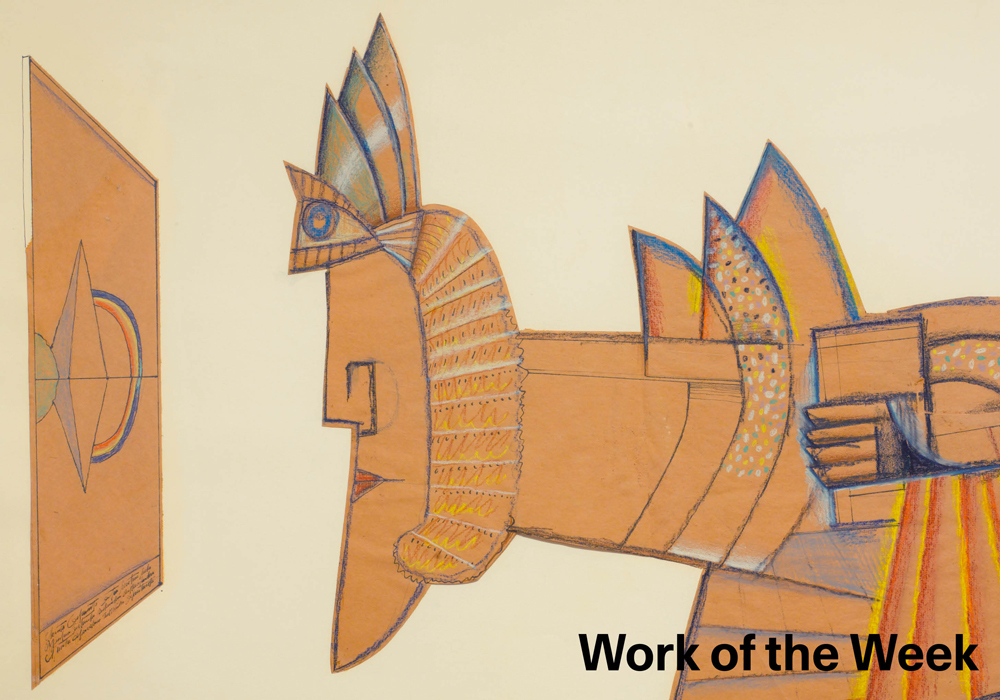

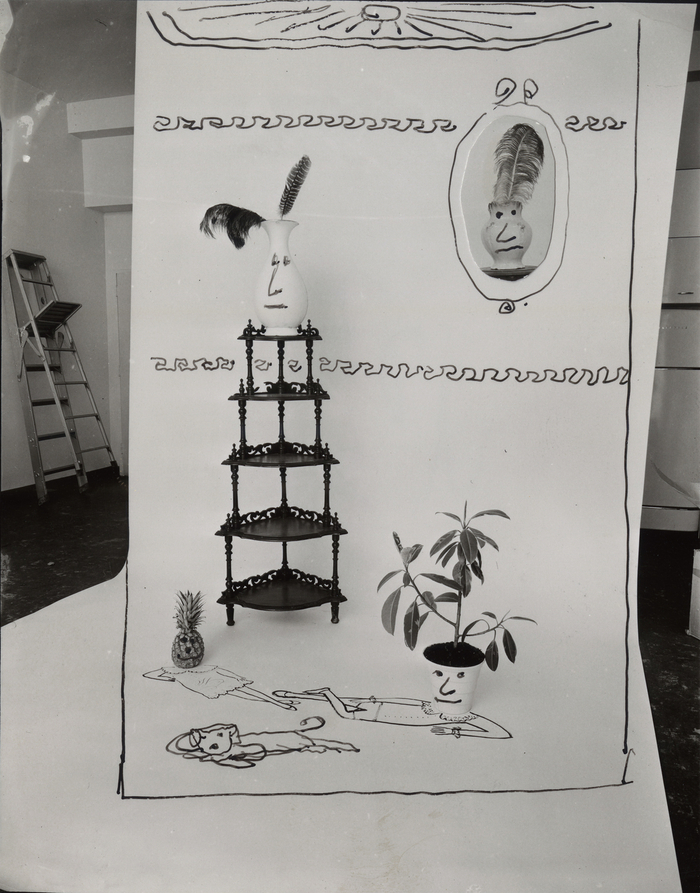

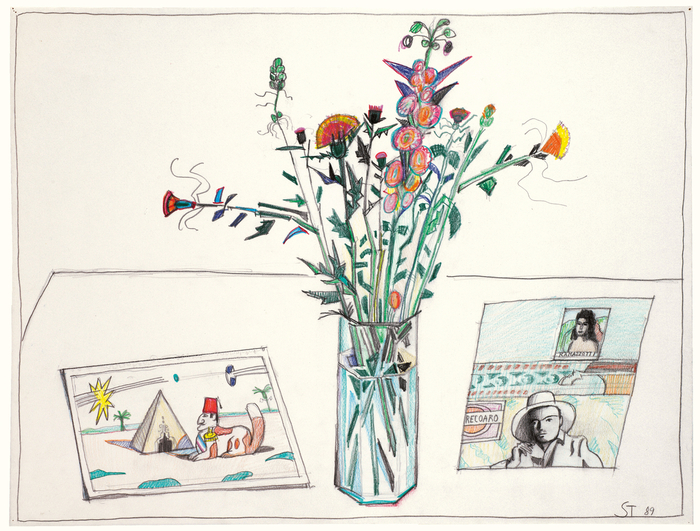

Indeed, another aspect of Steinberg’s work is the image within an image (so, a play on the interiority of the image itself). A photograph from 1950 shows a sculptural still-life of a plant stand, vases and a pineapple set up against a photographic studio screen (the studio still visible within the frame however), the print of which Steinberg has augmented with further line drawing (adding children lounging among the pots on the floor); there are several drawings of the artist at work, the composition the artist is working on within the self-portrait viewable to us, the viewer, outside the image; or within several depictions of jumbled interiors, paintings, yet more images with images, hang on the wall.

What we end up with are layers of visual reality (or unreality – the imagined), in which pictures are drawn within pictures which might have ended up in magazines but are now online. The confusion of Steinberg’s work, both mental and spatial, seems as pertinent to our times today as they were when the artist first made the work. So much for progress then.

All images © The Saul Steinberg Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York