The 2024 edition, titled Drift to Return, captures the city’s art scene in a state of flux

At Beijing Commune in 798 Art Zone, a district of former military factories turned into cultural spaces, the insides of three crudely constructed shelters and a tea house (or chashitsu) look like studios used by art students. In each room, scrappy metal sculptures, painting studies depicting biblical stories and Soviet leaders, as well as commercial, decorative objects – a cheap-looking wood-relief of an entourage of Daoist saints, for example – are placed on the floor and hung on the wall, amidst brush smears and colour tests. Despite the quaint, saintly subjects and the mono no aware structures that contain them, everything looks intentionally undone and decontextualised to chaotic effect; an oil sketch of the Flight into Egypt backdrops a makeshift table set made of a traffic sign and industrial chairs, while a lookalike of Giacometti’s Walking Man (1960) wears a pair of Nikes. These works are by Zhou Yilun, who studied painting at China Academy of Art in Hangzhou in the early 2000s, which was then situated on the edge of the city where the streets make way for fields. His exhibition, SANLIANZMK, takes inspiration from the temporary shelters farmers would put up near the Academy using the materials that students had thrown away. Next to the wooden structures in the exhibition is a stage, upon which items scavenged by Zhou from sculpture factories and websites selling second-hand goods have been assembled to form figurative shapes and totem poles. There’s a blurry line between what constitutes art and what is solely utilitarian. Zhou uses what is essentially waste to construct a material history of urban culture captured through the skins that it constantly sheds – and the meanings that we tattoo upon them.

Beijing Commune, where Zhou’s show took place, was one of 34 galleries and institutions that featured in this year’s Beijing Gallery Weekend (30 May–4 June), including a central exhibition that focused on emerging artists. Besides the 798 Zone, three other art districts in the city participated in the event: Caochangdi, Blanc Art Space and Beijing CBD. Each region has its own unique history of urban planning. Caochangdi, for example, not far away from the 798, developed out of an artist village that was instigated by Ai Weiwei in 2000 (his own studio was demolished in 2018 as a consequence). It now houses ShanghART’s newly renovated space, as well as dozens of well-known artists’ studios (Zeng Fanzhi and Wang Xingwei both work there); while the district’s Taikang Space relocated to central Beijing last year as it rebranded itself as the Taikang Art Museum. Blanc, established in 2021, is a duty-free zone located close to Beijing International Airport hosting international galleries such as Lisson and Massimo de Carlo. Its relative removal from the city centre means that it largely attracts buyers rather than the general public.

Titled Drift to Return, this iteration of Beijing Gallery Weekend aspired to ‘strike a delicate balance where exceptional international art practices can be retained and shared with the local Chinese audience’, according to its publicity blurb. But Drift to Return also puns on piaoliu, for which the more common homophone in Chinese means being adrift and rootless. With this slip, intentional or otherwise, the title’s general sentiment is somewhat despondent (unlike last year’s edition, in which galleries were competing to impress under the title Visibility, after the period of lockdown that ended in January 2023). That seems to be how many institutions and galleries interpreted the theme, too. Taking its name from feminist poet Adrienne Rich’s eponymous book, An Atlas of the Difficult World at Macalline Center of Art gathers works from its founder’s collection and includes previous commissions – this move itself reflective of financial restraint – to negotiate ‘the tumultuous and unfathomable conditions of today’s world’. At the entrance, Feng Zhixuan’s Wind Chimes – Sousa Chinensis (2024), a steel skeleton of the titular animal, commonly known as the Chinese white dolphin, hangs from the ceiling like a sacrifice, if not Christ on the cross. It speaks to how a sense of modern, perhaps national, identity built upon the governance of species and nature hangs in suspense (coincidentally, a state-funded documentary series, Chinese White Dolphin, was released on China Central Television’s Channel 10 the day before Gallery Weekend’s opening).

The one and a half years since the end of lockdown might have given galleries and artists enough distance to contemplate on the pandemic. CLC Gallery Venture, a partnership between three galleries (C5Art, C-Space and Space Local), is showing Yang Guangnan’s paintings and installations that reflect upon changes in Beijing’s urban landscape. Titled Borderlands, the exhibition starts with a video work, Untitled (2014), which shows footage taken by the artist as she paced the streets of Heiqiao Art Village before it was demolished in 2017 to be developed into an embassy and business district (from 2010 onwards, more than 20 artist villages including Sunhe and Naizifang have disappeared for various reasons all relating to urban planning developments and demographic control). With the screen installed inside of a steel water-fountain that has been half submerged in sand, the piece evokes danger, suggesting that daily memories can be both submerged and drained away. Further into the main gallery, seven paintings on wooden boards show hexagonal grids over amorphous shapes in saturated colours, recalling images created by infrared cameras (which were used to monitor the body temperature of those occupying public spaces during the pandemic). Taken together, there’s a sense that artmaking is predicated upon urban development and its governing policies; a sense that vision can be barred, mediated and erased. Across the street, the gallery’s project space, C5CNM, is showing Zhan Wang’s installation Not Touching Prevents Complete Blackness (2024–), a big wooden cube upon which the artist and his team used brushes of varying sizes to apply black wall paint in short, rectangular marks to the cube’s white interior walls. The only requirement was that each brush mark needed to maintain a distance from the others. As the available space on the walls became smaller, more marks by even smaller brushes were added. A reflection on space, distance and a kind of mathematical infinity, it seems to suggest the endless potential of creative gestures and surveillance – after all, censorship and how to creatively eschew it, are two sides of the same coin.

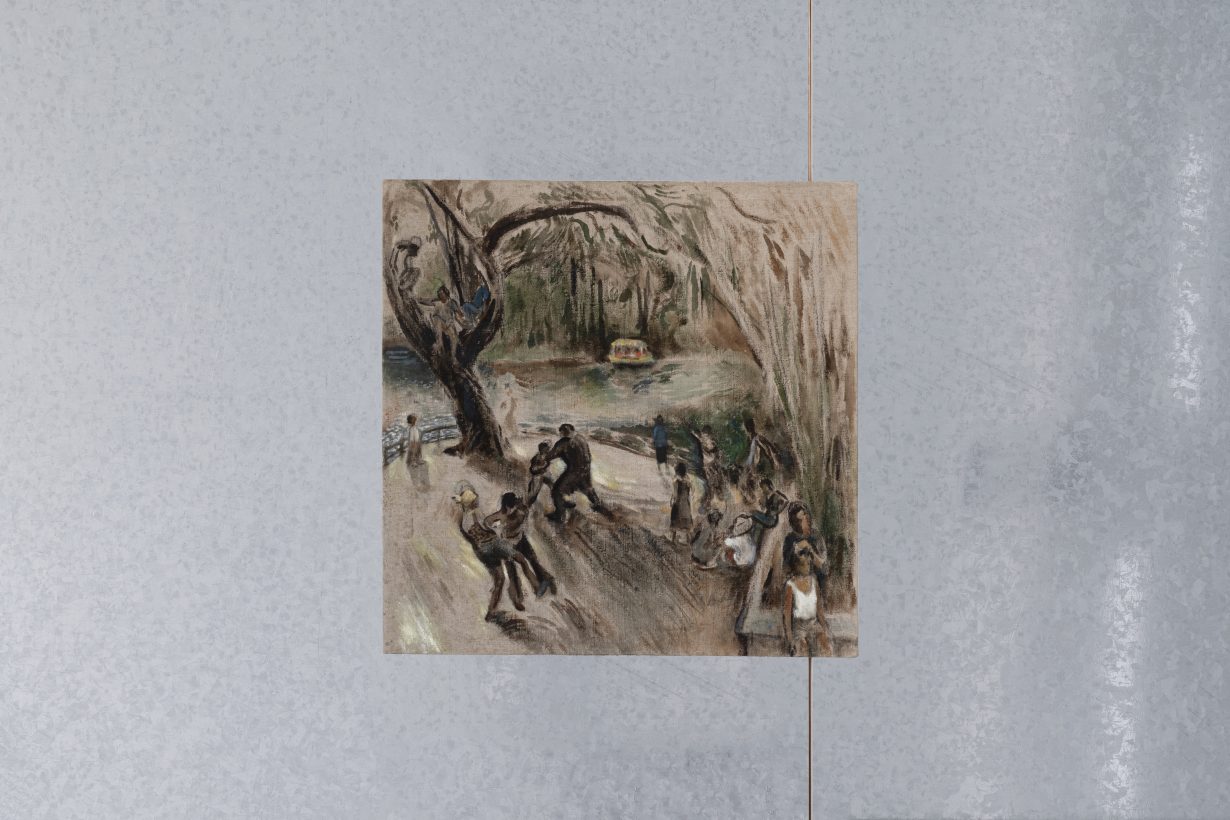

One way to evade the limitations of censorship is through curating shows that are closed to the public, so that the gallery wouldn’t need to report to community centres. If you walk past a big window on one corner of the central square in 798, inside you will see what looks like a food delivery guy (dressed in the yellow uniform worn by Meituan employees) who is trapped in a gallery office. Opened this year, this is Magician Space’s new project site. The show includes works from the private collection of artist and curator Liu Ding, who organised the exhibition (and recently curated the Yokohama Triennale along with Carol Yinghua Lu). Room of Boundlessness takes its title from a line in a poem by canonical eighth-century poet Du Fu in which he laments his poverty at an opulent garden party; and as the crowd dispersed he found himself all alone amidst a boundless space – a solitary, powerless position that the literati of latter generations heavily empathised with. Upon entry, the space looks like a storage room: all works have been displayed on the floor facing the walls. They have been organised chronologically, starting with Hu Shangzong’s self-portrait, which has a suicide note written on the back of the canvas (painted in 1969, one year after the onset of the Cultural Revolution), and ending with Liu Ding’s plastic mannequin – the Meituan person that can be seen from outside – Waiting for Orders (2024). During the pandemic, many who worked in the food delivery industry would find themselves temporarily trapped in places due to pandemic control. Here, the mannequin holds a bottle of Chabaidao bubble tea in its hand and watches TikTok videos that play nonstop on a phone. Surrounded by the semi-reflective walls covered in galvanised metal sheets – which makes the space feel makeshift, uncomfortable and constricting – you would see yourself vaguely reflected, amid works that speak of our solitude at times of crisis.

Beijing’s art scene is known to be more local than that of Shanghai’s. Its Central Academy of Fine Art (CAFA) almost dominates the local art circle and this old-fashioned institutional presence can be felt at Galleria Continua, showing CAFA professor Qiu Zhijie, and Galerie Urs Meile, showing its alumna Cao Yu. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Beijing also has an underground scene that emerged from a less open marketplace, as well as a heavily charged political climate. This year there was a clear attempt to be more international with Aria Yang, who like many young collectors received her training abroad, directing a curatorial programme that somewhat bridged a gap between local and international tastes. At White Space, hearing-impaired artist Christine Sun Kim and her partner Thomas Mader’s exhibition explores deaf culture and Kim’s relation to breathing; at 798Cube, the works of Yunchul Kim, who represented the Korean Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale, explore machines and matters through a posthuman, cosmic lens; and Roksana Pirouzmand, who experimented with photographic paintings made on clay during her residency in Jingdezhen, a town famous for its porcelain production, chews on memory and loss.

Having been cut off from the rest of the world for several years, the art scene in Beijing’ also feels somewhat forgotten on an international scale and is picking up at a slower pace in comparison to Shanghai, which recently peaked again with its Antoine Vidokle-curated Biennale. That perhaps explains why the two other art fairs taking place this year, Beijing Dangdai and Jingart, opened at the same time instead of a week apart as is usual. Beijing doesn’t seem to care about being a trendsetter, and considering how much geopolitical significance the city now wields it probably doesn’t need to have any aspirations of this kind. But as of now, judging by this Gallery Weekend, there is a sense that the megacity needs a pump of adrenaline to shed its lethargy.