Minor Streets at Carl Freedman Gallery, Margate revives the unmodish influences of the kind of social realism that emerged in Britain during the 1930s

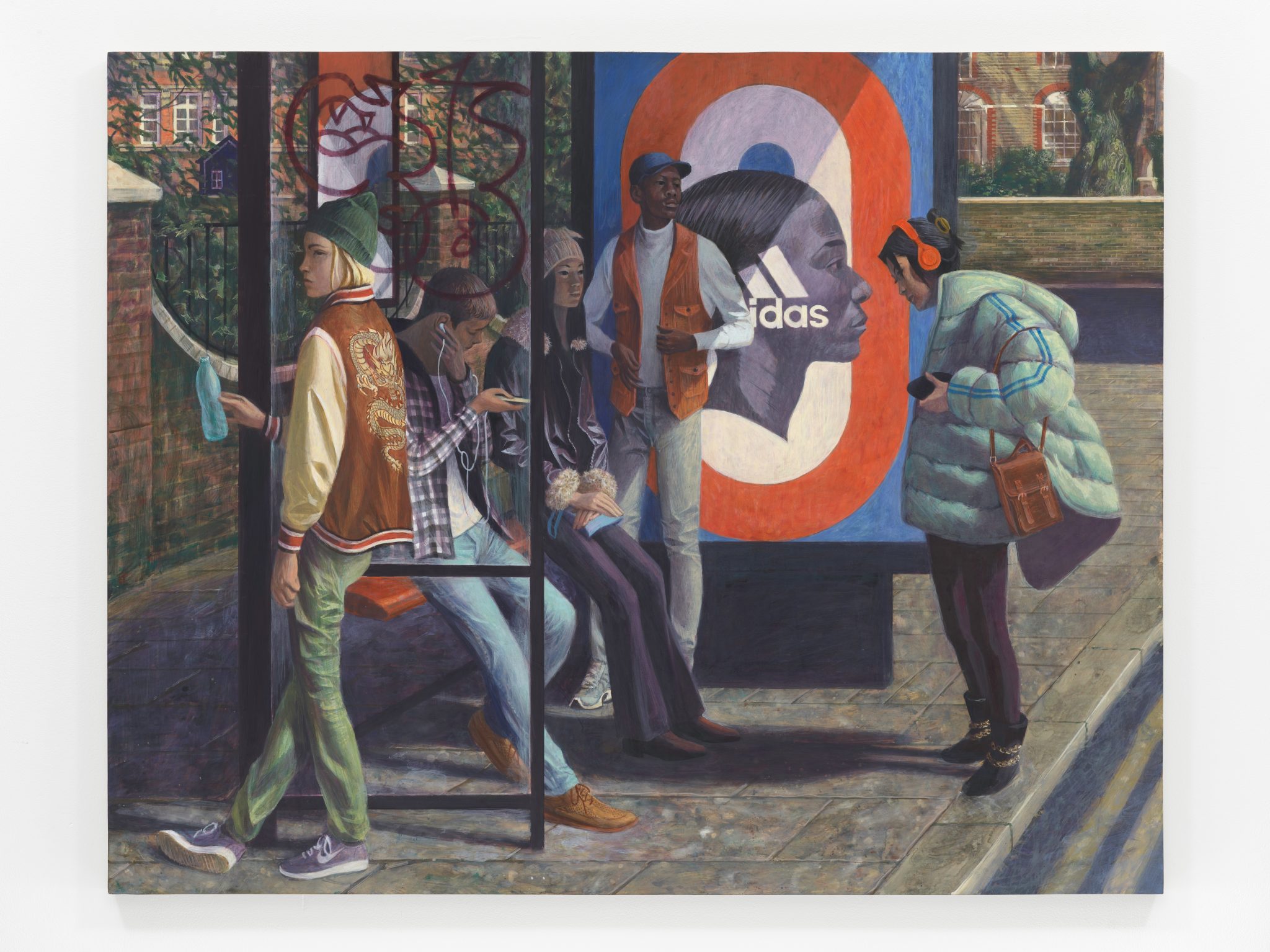

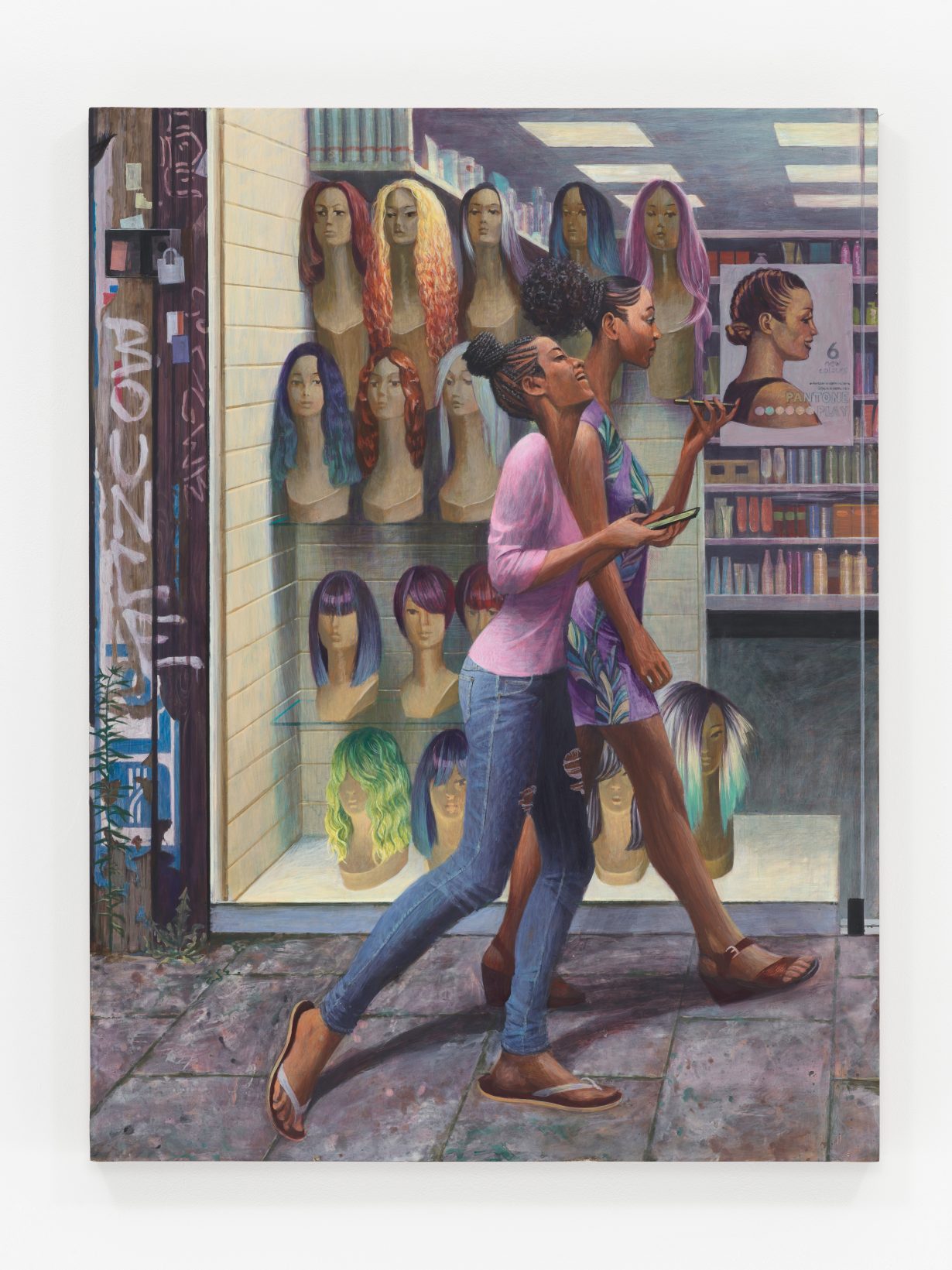

In Benjamin Senior’s idyllic, jewellike paintings, London is beautiful. So are its inhabitants. Nothing is urgent, no one runs. A bright daylight or warm evening sun makes everything glow. Although the city’s pavements are dirty, its bus shelters tagged with sinuous graffiti, Senior’s multiethnic subjects exude grace, good looks and a stilled, introspective calm. The moments Senior’s urban dwellers inhabit are those of delight taken in small pleasures, or the business of attending to the activities of a working day, or the lassitude of waiting: a young man lights his mate’s cigarette, as they pause outside a women’s hair fashion shop, bewigged model heads lining the shelves inside (Smoke, 2023); a stall-holder in a peach-coloured turban, white kameez and burgundy waistcoat examines his stock of saris and dresses, also displayed on the mannequins behind him (Sari, 2023). Scenes of young people at bus stops proliferate; a young woman sits on a bus shelter bench, hand on chin, lost in thought, looked over by the fashion model who gazes out from the illuminated adverting poster.

Senior here draws on the unmodish influences of the kind of social realism that emerged in Britain during the 1930s. Painters such as Stanley Spencer, Harold Williamson and Evelyn Dunbar were among the many artists who assimilated a hard-edged, modernist clarity to conjure an idealised view of everyday life and ordinary people, in deliberate, sentimental reaction to the traumas of the First World War, and to the political clouds then gathering over Europe. The consecration of ordinariness, back then, was a retort that the goal of a good society was an ordinary life to be enjoyed, not revolution and war. Senior’s urban scenes revive this sentiment, and though contemporary Britain isn’t threatened in the same way, there is still a sense of disjuncture; in real Britain teenagers are stabbed, urban infrastructure is breaking down and the local shops are going bust.

But then Senior’s paintings have for many years delighted in the compositional and decorative quirks he deploys to remind us this is still a dream. Everywhere in Minor Streets, its inhabitants are surrounded by simulacra and representations of people – shop-window dummies, advertising campaigns – while the ‘real’ people take on the unassuming glamour of fashion models. Senior’s lasting taste for exaggerated compositional devices, visual puns and metonyms is more subtly insinuated into these paintings than in earlier works – the semicircular curves of a shop’s doorhandles project outwards in echo of the assertive thrust of the female mannequins seen inside, but are also countered by a man leaning back against the window, the patterned colours of his knitted tank-top reprised in the colours of the mannequins’ separate dresses (Green Dress, 2023).

In some cryptic way, these opposed forms of attention – a realist view of everyday life, but constituted in the compositional abstractions of the painting – come together to produce something utopian, in the sense of an absent world made visible, yet still out of reach, in which, improbably, all things connect to each other. It’s epitomised in the scene of Colour Play (2023), in which two tall young women stride past another beauty store, laughing and smiling at whatever is animating their smartphones. They are ‘black’, while in the shopwindow are ranged ‘white’ wig dummies, their tresses dyed every colour of the rainbow. Here, ‘race’ is not colour, social life is harder to change than hair dye and painting cannot do much about it. Yet in those verbal-visual slips between colour and colour, Senior’s visual ‘abstractions’ keep hinting at an ordinary world to be remade, an ‘elsewhere’ always present in the ‘here’.

Minor Streets at Carl Freedman Gallery, Margate, through 12 November