The 14th edition, Estalo, postponed following the 2024 flooding of Porto Alegre, considers ideas of the world in overload

For a while now there has been a glitchy band appearing on my laptop screen. It comes and gloats over my impending misfortune before disappearing just as mysteriously. It is, I know, the harbinger of my computer’s death. One might take the odd, increasingly frequent glitches in the weather as signalling something similar. In 2024 Porto Alegre, in the south of Brazil, flooded. Days of rain broke the city’s riverbanks and water coursed through the streets, destroying houses, taking lives and, the least of the tragedy comparatively, rendering many of the Bienal do Mercosul’s 18 venues unusable.

The Bienal was postponed, and while the calamity isn’t mentioned in any of the accompanying curatorial texts, ideas of the world in overload, humanity glitching and visions of visceral, irrevocable change fill the show. Not that it’s all doomerism: some of this stuff is downright accelerationist, a look to sweeping away old orders to make space for new ideas and identities to flourish. At Farol Santander, a cultural centre belonging to the Spanish bank, and under a preexisting stained-glass roof light inscribed with words (in Portuguese) like ‘work’, ‘progress’, ‘economy’, Berenice Olmedo has installed statues of four walking figures, each individually titled and from 2024, in iron, silicone and other materials: Giacometti reimagined for a cybergoth future. Nearby is a series of luminescent kinetic lamps by Yunchul Kim, Dust of Suns II (2022), strung up in a forest of wires on a hulking black aluminium tripod, the assemblage reminiscent of Krang, the evil cryogenic brain from Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. If this feels like the coming together of a supervillain and his cyborg army, then Marina Rheingantz’s murky polluted landscape paintings, all impasto greys and browns, and Urmeer’s logo-style paintings of an anthropomorphised sick and dying Earth (like mascots for the end of times) do nothing to allay the apocalyptic fear.

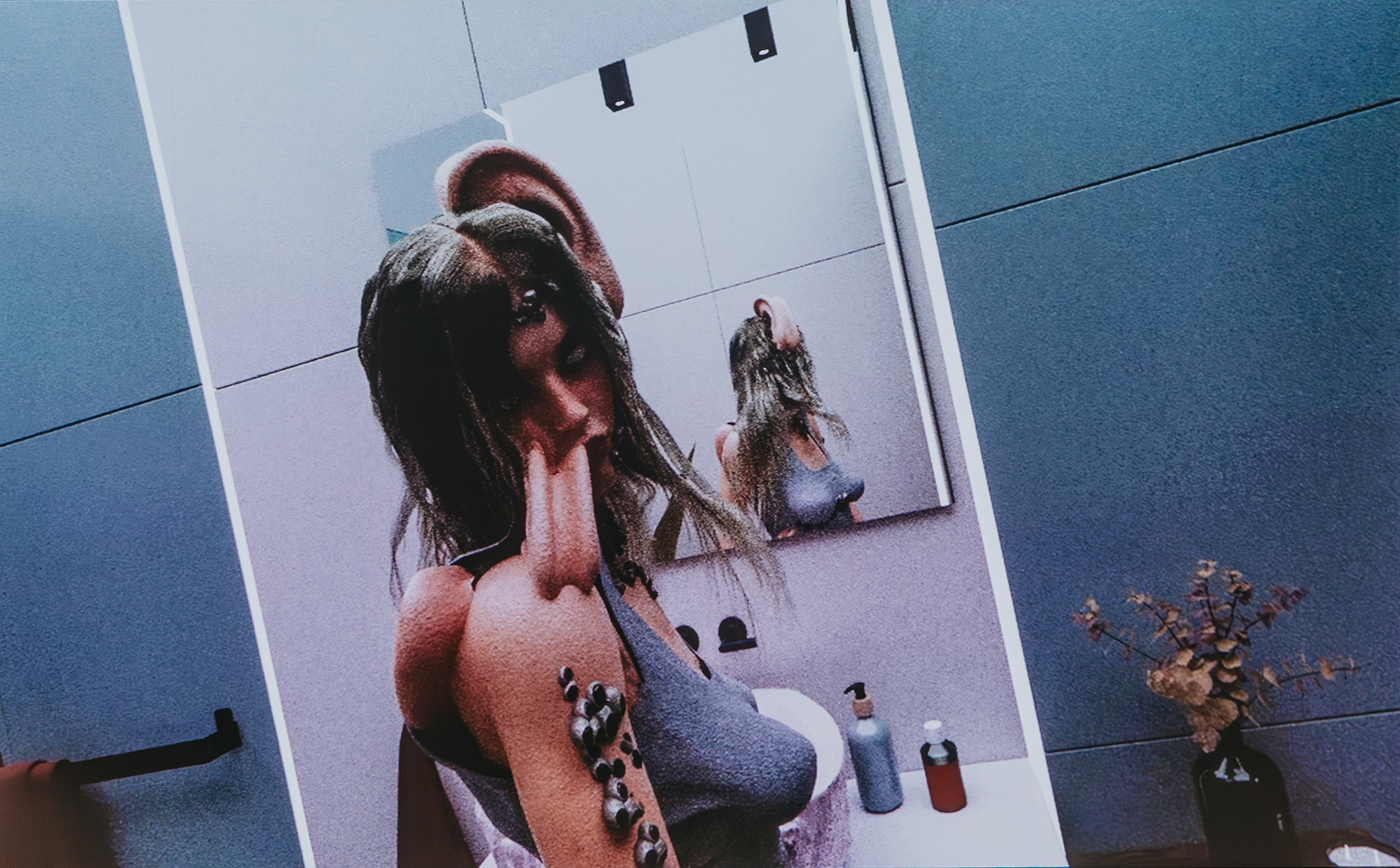

Projected in a dark room tucked away at the back of the gallery is Nam June Paik’s vaunted Global Groove. Originally made for public service TV in 1973, it is a dadaist manifesto for a media-saturated, interconnected world, one that has largely come to pass. Paik’s vision was one of techno-optimism, however, and his presence shifts the reading of the previous works and those encountered in the other venues to encompass a more generous vision of an adapted world, in which humans are transmogrified by a hybrid mix of technology, mythology and species adaptation. Vitória Cribb’s projected videowork Echoes of a Wet Finger (2024–25), for example, is at first glance nightmarish: an animated female figure, her body grotesquely augmented (a giant ear extends off the side of her head, a tongue rolls out of her shoulder), tests out a series of repetitive stretches and gestures. Cribb’s Chris Cunningham-recalling avatar could also, however, be envisioned as a model of adaptation and bodily autonomy (Cribb is a talent, but hers is one of too many videogame-inflected, postinternet-ish videoworks within the show, which tonally risks repetition).

At the Museu de Arte do Rio Grande do Sul, this cyberhuman, cyberother future is foreshadowed in Nereyda López’s woven mythological sculptures inspired by her Cocama and Tikuna heritage – a female child with a long, winding serpent’s tail, two paper-sculpted and painted creatures, big eared and smiling with long limbs – and in the barely perceptible ghostly figures that emerge from Awilda Sterling-Duprey’s mixed acrylic, pastel and oil paintings. The body dissolves completely in the multiscreen animated skeletons of Özgür Kar and the noisy assault on the senses in the late Gretchen Bender’s Dumping Core (1984), a gloriously roaring 13-monitor soundtracked abstract animation that leaves you feeling as if you’ve emerged at dawn, eyes sensitive but euphoric, from a particularly subversive end-of-the-world techno party.

Ideas of social and environmental breakdown, and opportunity arising from the ashes, recur throughout the Bienal’s venues and the work of its 77 artists: among the ten artists whose work is installed at Usina do Gasômetro, a former power station, Tirzo Martha, from the Caribbean island of Curaçao, has built E Pesadiya a libra mi di mi soño (The Nightmare Freed Me from My Dream, 2025), a giant toxic-looking tree of black plastic bags and old tires. But 24 evocative photographs of Bolivian folk dances and religious costumes, taken during the 1950s by Damián Ayma Zepita, suggest communion beyond the material world. In Randolpho Lamonier’s maximalist installation for the Museu de Arte Contemporânea do Rio Grande do Sul, toys, teddies, monkey masks, skeletons, lamps, portraits and monitors playing out news reports of 9/11 are piled together with rambling confessional texts handwritten on the walls. A sense of personal breakdown reflects back a civic one: for Fundação Vera Chaves Barcellos, US-based Iraqi artist Ali Eyal sent his beguiling fragmentary watercolours of world leaders, collectively titled But let me finish please. Let me say something. (2025), by post, each shown atop the packaging in which they arrived; while Firas Shehadeh repurposes Grand Theft Auto footage for his video Like An Event in a Dream Dreamt by Another – Insomnia (2025) to visualise a monologue on Palestinian militance in the face of Israeli assault. The gameplay sunsets and the freedom of movement the artist’s avatar enjoys posits a utopian, postmaterial future beyond the cages of the current system.

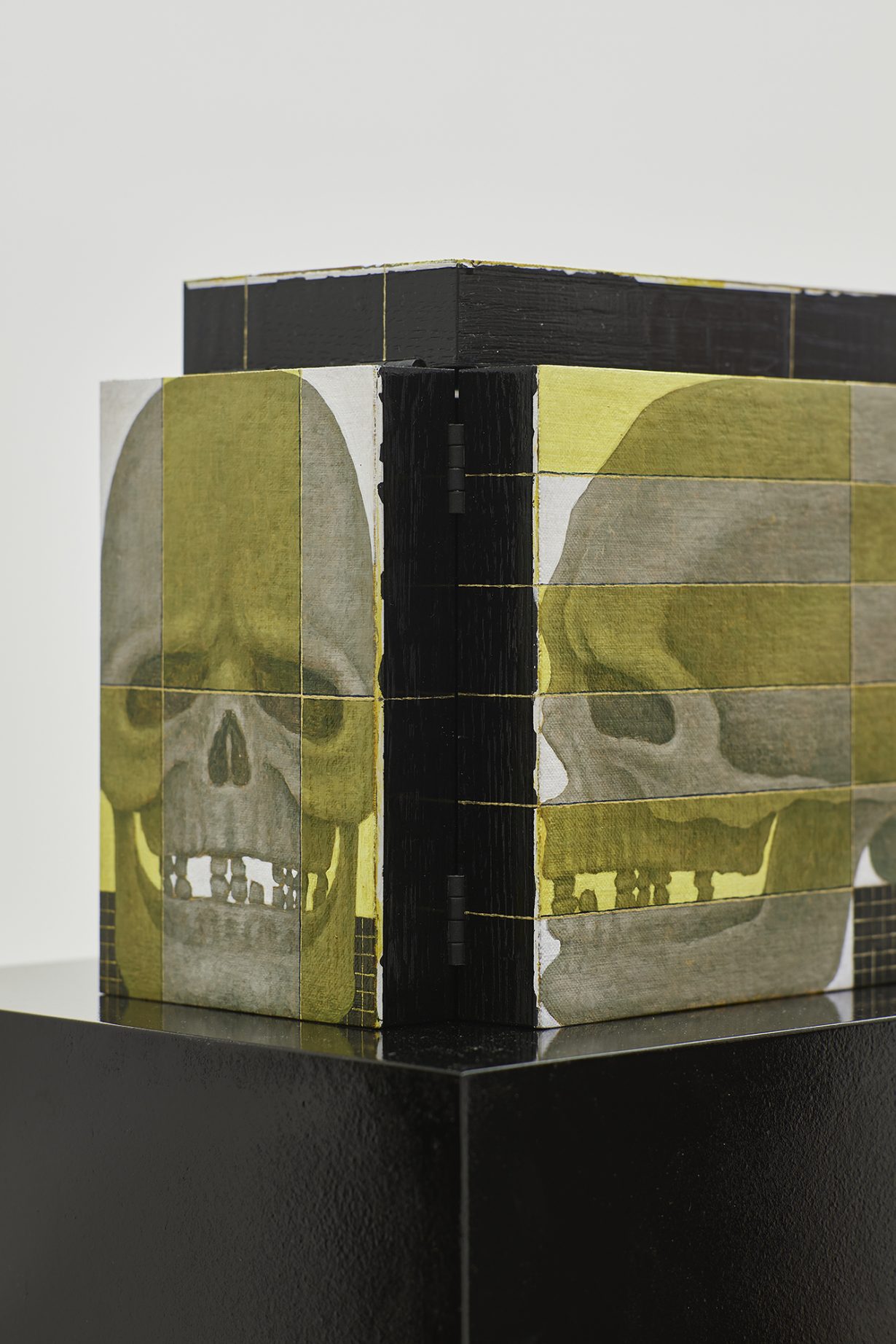

Fundação Iberê Camargo has the largest concentration of work and feels the loosest curatorially: Rodrigo Cass’s austerely conceptual monochromes, for example, hang near Venuca Evanán’s paintings of Quechua life and rituals on wooden architectural fragments. There are highlights, though, especially when mutant extraterrestrial or supernatural bodies are the focus: Maya Weishof ’s recently painted orgiastic canvases, full of lust and life, and Camargo’s 1980s ghostly Fantasmagoria paintings are neat bookends to the five floors of the exhibition. A series of spritelike figures emerge from blocks of rough wood in Zé Carlos Garcia’s series Suite (2025); black silhouetted figures cavort with animals in a room of paintings on wood by Santiago Yahuarcani. If the Bienal at its best moments presents a dance to the death, Armageddon imagined as a fiesta, those ideas are articulated supremely well by a series of quiet but revelatory sculptures by Li Yong Xiang – small hinged wooden boxes and dioramas presented on pedestals. One is finely painted with a skull, another reveals a skeleton and a blood-red forest behind a set of sliding doors. The final two, the spookiest, are an empty subway station and a desolate anatomy theatre. They are uncategorisable as artworks, creepy in their motifs, but their literal articulation on the hinges offers a sense of bodily autonomy, possibility and escape.

14a Bienal do Mercosul: Estalo, Porto Alegre, 27 March – 1 June

From the Summer 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.