“All humans will realise that they are born creators, and the meaning of ‘artist’ will change”

For half of her life, Bonnie Camplin has been at work on a project to understand the nature and structure of reality. She began with her own subjective experiences of mental health and continued to explore a range of esoteric subjects including Celtic ritual, quantum physics, extrasensory perception, experimental theatre, so-called abnormal or anomalous psychology, military science and femtotechnology [smaller than nano]. She’s spent 25 years syncretising this research into a unique, fascinating theory of perception, ontology and the spiralling nature of time and space.

The British-born Camplin, who is in her early fifties, has primarily expressed these ideas through drawing and painting. Initially she worked with refined representational draughtsmanship and gradually distilled her marks to scribbles, stick figures and theoretical propositions, produced while in a trancelike state. For her, art is a communion with the immaterial – what she calls a “gnostical modality” or a “dimensional gate” – and the objects she exhibits are simply the material residue of those transmissions.

Her other earthly byproducts have included films, music and photographs. Her early work also involved acting, dancing and staging happenings in nightclubs around London’s Soho. She has collaborated with Paulina Olowska, played in a band with Mark Leckey and exhibited with Matt Mullican, one of the few artists with whom I might tenuously compare her practice of lifelong inner exploration.

In recent years Camplin has focused on pedagogy. Her later exhibitions took the form of workshops and experimental research facilities, such as in her 2015 Turner Prize show The Military Industrial Complex. Many of her most adventurous interests, such as the holographic universe and terrain theory, have been articulated in lucid, exploratory lectures. Since 2018 she has stepped entirely away from making physical, capitalist “output”, instead focusing her energy on more direct interaction with the “beyond-human world” and her interactions with students as a teacher at Goldsmiths, University of London.

For the following interview, Camplin called me on video from her flat in London Bridge. She had recently returned from her second home, in Cumbria, where she lives off-grid in a yurt on the edge of an ancient forest. She answered all my questions with a cool, gentle composure, even while discussing the most wild, controversial hypotheses. The conversation lasted for over two hours and felt bountiful in every moment, energised by Camplin’s intellect and grounded by her preternatural sensitivity.

No Longer an Atheist

Ross Simonini I noticed that you often use the word ‘survivor’ or ‘survival’ when discussing your work. Is this a central concept for you?

Bonnie Camplin Yeah. It means that I’m a perceiving organism in the process of survival. And I think for me survival, creativity and love, they’re all the same movement. I’ve been through art school and I’ve been around some very, materially speaking, privileged people. And I don’t come from material privilege. I come from intellectual privilege and mental-freedom privilege, so for me it’s all about trying to survive and stay free, to stay sane and be whole. I’m also a bit of a prepper. My dad was a total prepper. And the whole ‘MAD’ (Mutually Assured Destruction), the threat of all-out nuclear destruction, was a thing that was just pumped out constantly by the media through the 70s and the 80s, the Cold War, so we lived with this constant rhetoric about ‘Duck and Cover’, tomorrow, every day could be your last day! Because the whole world could just be obliterated by ‘Mutually Assured Destruction’.

RS Is the survival instinct crucial to the art that you’ve made?

BC Yeah. On many levels. The only reason I ended up doing art was because in religious education we were supposed to read and demonstrate our comprehension in writing, but I would get that done quickly and spent the rest of the time drawing pictures. And so my religious education teacher said, “Oh, you’re going to do art” and I said, “What else am I going to do?” Art is also a really good story or ruse for avoiding the mental health system. If you’re an artist, you’ve got a cover story, haven’t you? Whereas if you’re just a sort of eccentric person with too many ideas, you’re potentially a candidate for the psych ward… At a certain point I was on the edge of that candidacy, even though I’m actually a very, very sensible person. It’s kind of like, where are you? Where’s your harbour when your life doesn’t have any kind of plan? But I do think the gallery system is a conspiracy against the artist. It’s not a harbour. It’s not a safe place for artists. It is a sanctioned space, and I’ve been trying to minimise my interaction with it and still be able to have some good conversations with some good people. I also wonder what kind of professionalisation-specialisation, relegation and reduction and/or capture kind of effects it has on spiritual power. Do you feel that?

RS Yeah. I see two parallel paths with art. You could call them the material and the immaterial, or the cynical and the earnest. It’s easier to reject one path and embrace the other totally, but for me the challenge is to walk both at once.

BC That is a good way of putting it. Being multilingual. I guess I’m saying that galleries don’t really support you in a way you might fantasise that they should do when you’re in art school. And it’s just that all I want to do is to do whatever I’m doing. And I haven’t made a drawing in over two years, because I haven’t felt the need.

RS Have you turned down many shows?

BC Maybe three years ago my gallery said, “Let’s do a show” and I said, “I want to hold a series of conferences in the gallery space. Where we really get into this thing about nature reconnection and creativity, perception and cosmos and natural law and land rights.” But my gallery wanted objects. So fair enough.

RS It’s been four years since your last exhibition, right?

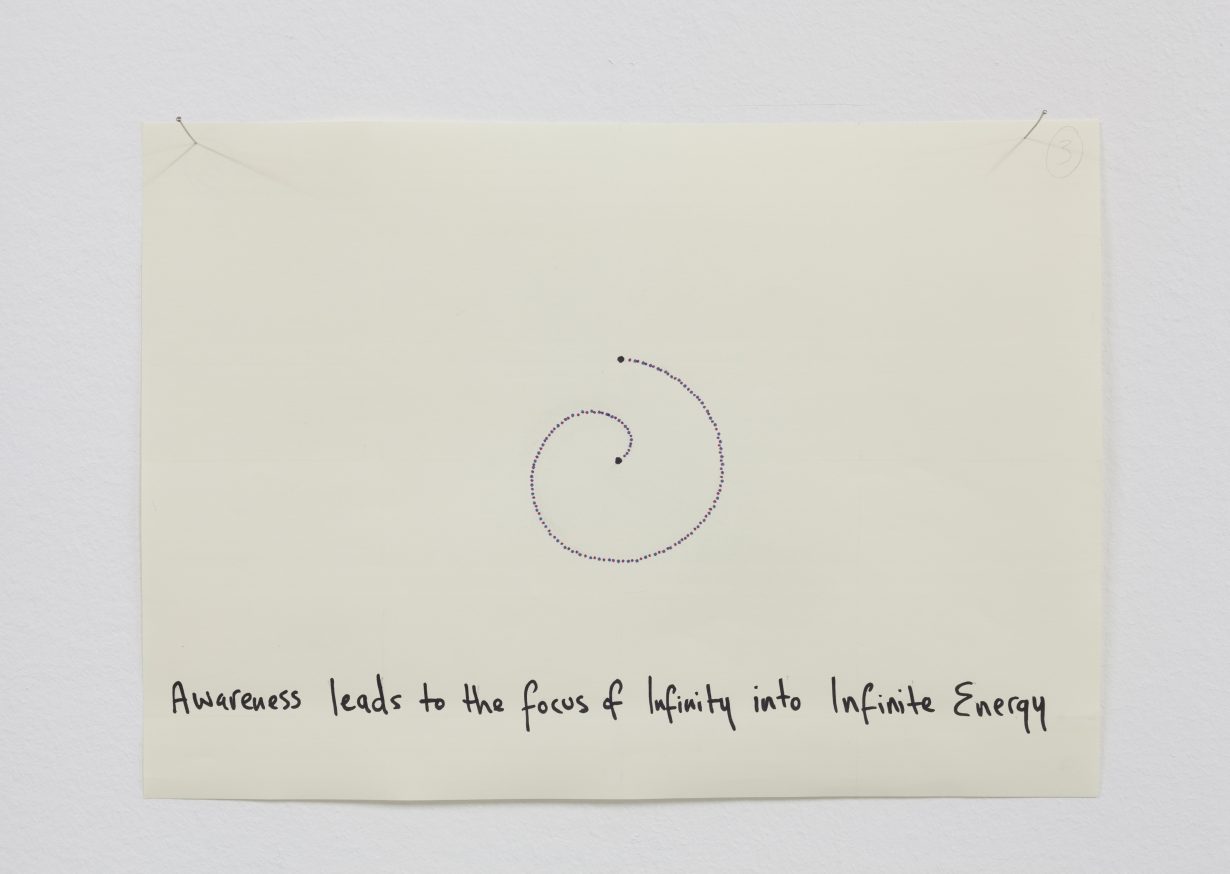

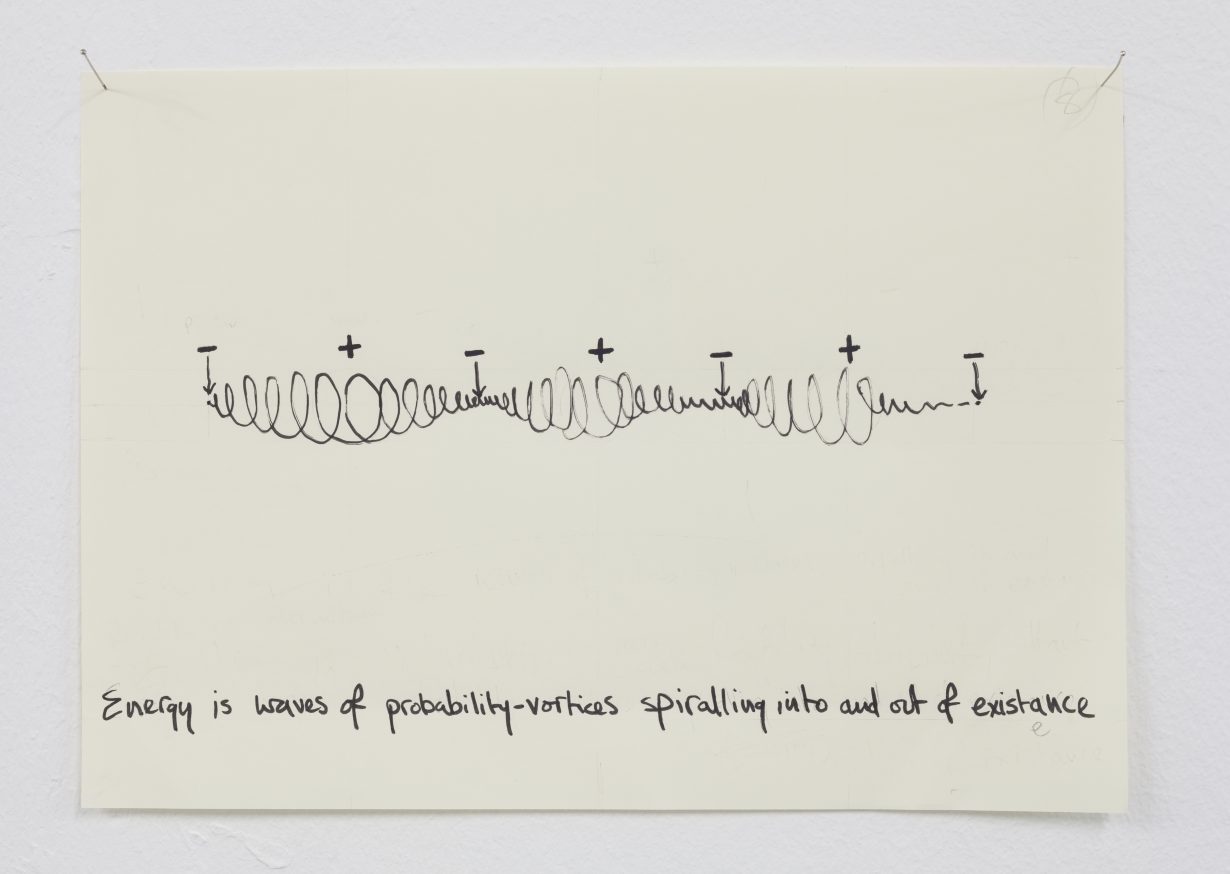

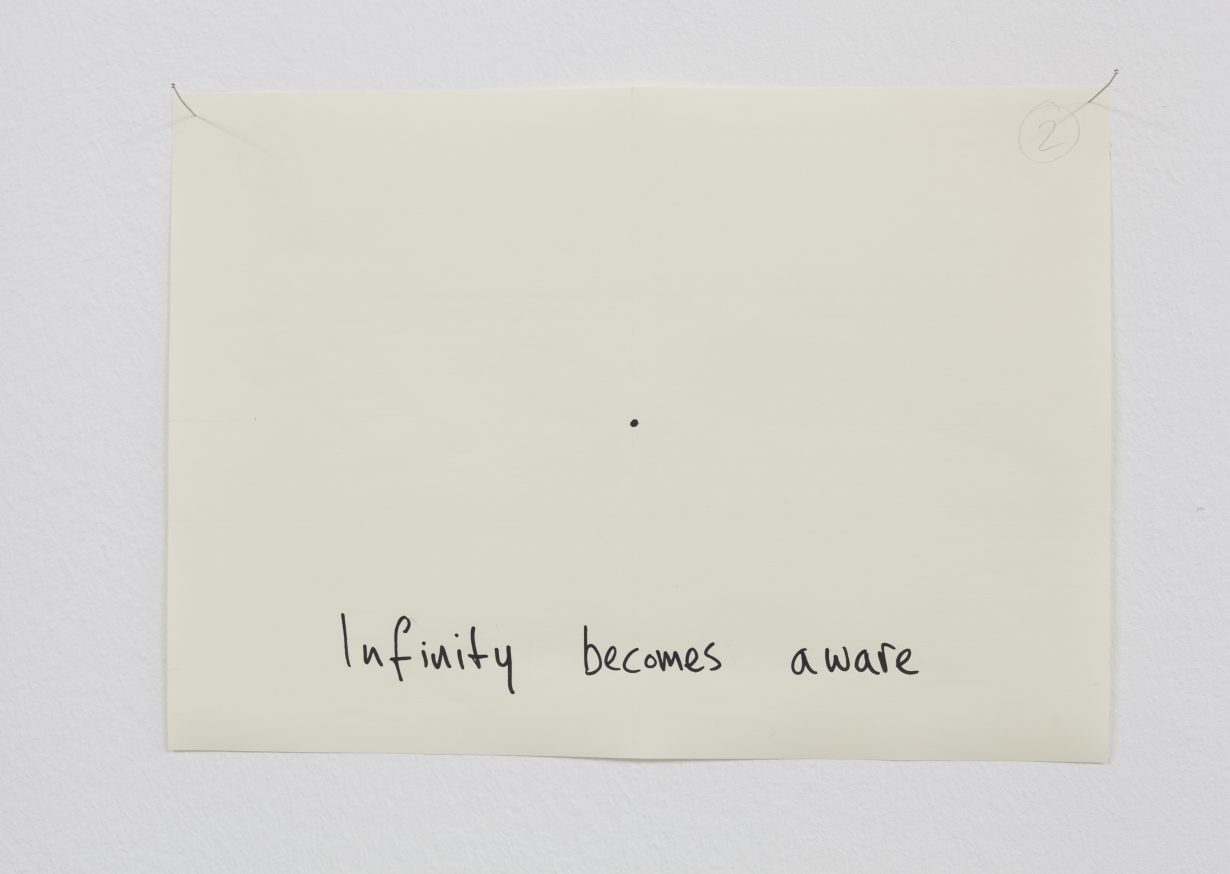

BC In 2018 I did a show in Berlin called Free-will Presupposes Full Disclosure [at Ebensperger]. That included the spiral drawings. That was amazing because I actually met [quantum physicist Werner] Heisenberg’s family and they saw my spiral cosmogony diagrams. I got to see them seeing my drawings! So those drawings are the last thing I did, and I was so massively focused and downloading a lot when I made them, and I just feel that I can’t really top what I did with those drawings. I think they’re brilliant!

RS What about the drawings was so successful?

BC I just had total clarity and focus. It was literally like a lifetime’s work of asking about the structure of reality. And I was able to pull it all together. I synthesised [naturalist and philosopher] Viktor Schauberger’s principles with [artist and writer] Dr Walter Russell with the Ra Material downloads [transcripts of communications from the Venusian group-entity Ra, published 1982–84], specifically the ‘Probability Vortexes’ and the ‘zero-point’, with my own insight and all this that I’ve been completely obsessed with since I had a near-death experience when I was twenty-five. Before then I was an atheist. And then after that I wasn’t an atheist anymore. And I had this experience of time and spirals and the zero-point, and I’ve been trying to really understand that ever since. So that’s 25 years of obsessively researching about physics and motion and specifically spirals. And I just feel like I really cracked it, and I haven’t really done any drawings since.

Supposedly Fringe Theories

RS The way you talk about art is through the lens of science. Are you interested in art without science?

BC I very rarely go to see art. I’m also privileged, as I do get to see a lot of art because of my job. I’m not disinterested. It’s just that I don’t really have time to go to art shows. I’m just obsessed with certain things and it’s not art.

RS Has that always been the case for you?

BC Pretty much. Yeah.

RS So art was always a way to research and synthesise scientific paradigms.

BC Yeah, but not just ‘science’ – also other knowledge systems. And it’s taken me years to find my way to the actual scientists who I feel have the actual goods, because, for example, Einstein doesn’t. He thought the speed of light was a constant, but it isn’t. And through a lot of my research into very dark stuff, military special-programmes stuff, what is apparent to me is that they’re not doing Einstein. They’re using weird, obscure, supposedly fringe theories such as those of Walter Russell, Dr Rupert Sheldrake and the like. That’s who they’re into because the world is a lot weirder than we’ve been taught in school.

RS How do you reconcile teaching inside the artworld that you resist?

BC Well, we have new minds coming in every year and they’re changing things. Pedagogy is a two-way street, isn’t it? I’m finding that a lot of them aren’t even interested in galleries. They set up these little shows, and it’s a lot more fluid and a lot less aspirant. Also, ‘spirituality’ is no longer a dirty word as it was 10, 20 years ago. So, there are these psychic girls that come through. They’re not marginalised now. They’re actually the ones who are doing the real research. Because they’ve got the confidence now, whereas 10, 20 years ago you really had to prove how rational you were just to be credible.

RS Which is a peculiar requirement of artists.

BC Yeah. I mean, criticality is key, but ‘critique’ less so. These are two different things, aren’t they? So, I fucking love my job. I wouldn’t give it up for the world and it gives me a lot of pleasure and I meet these great souls who come through. And I do have great conversations. And then, I’ve been trying to reword the public materials for our programme of study, actually, so as not to suggest that the gallery system is necessarily the ultimate destiny for an artist.

RS I heard you held a workshop on remote viewing when you taught at the Städelschule in Frankfurt…

BC Yeah, that was brilliant.

RS … and a trip to a boot factory.

BC That visit was part of a trip to the Polish mountains near Krakow that was [Jerzy] Grotowski-inspired. He was the experimental theatre director from the 60s who was really into quantum theory and perception and revitalising all these kinds of like mastery tradition stuff with his actors, bringing it all down to the archetypical. Paulina Olowska, a Polish artist and dear friend, she lives near there and she actually organised that trip to the boot factory for us. So that was just like a school trip. At Städelschule they have so much money that I had a personal assistant, and I would get him every month to organise field trips to factories and so on. And then I got the elbow from Städelschule. I just got kicked out.

RS Because of these field trips?

BC No; they just didn’t like me. Their paradigm seemed quite old-school to my mind, even though there were a lot of amazing students. It seemed to be kind of ‘dining out on its past’ of certain artists who had a certain cachet at a certain point in time; also the Frankfurt School etc and with Marxism as the chic doctrine. I wasn’t very famous and they do like to have establishment ‘names’ on the books there. The reason it’s free to study there is because the banks sponsor the school. And the banks will only sponsor if they’ve heard of the names on the faculty. But they hadn’t heard of me!

Living in a Hologram?

RS I’ve heard you used the phrase ‘the invented life’ to describe your work. What does that mean?

BC Oh, that’s not even my phrase. So, in the 90s I was in nightclubs where I was doing my creativity. That was the context. I was doing it for about 11 years. Me and my closest pals, we were all from non-materially-privileged backgrounds and so it’s a real precarity situation and we’re in financial poverty a lot. But we’re doing the best club nights and going to all the best parties and everything. We looked amazing and raw and so on, but we didn’t have a lot of cash. If we ever did have loads of cash it would be in a plastic bag ’cause we had done a good club night. And we were sitting around and doing that thing where, you’re really just trying to affirm and encourage yourself and each other along. I can even name the people, Sarah Churchill and Andrew Aveling. And we said, “We don’t have a plan, we just live in the moment of the invented life because we are literally having to make it up as we go along. We don’t have financial support. We don’t have a destiny. We might not even make it.” We didn’t think we were going to make it to age thirty. We all thought we were gonna die. That’s what we had in common.

RS And you did nearly die, right?

BC Yeah, I did have a near-death experience. But it’s also an attitude to life, which is now how I would understand that everything is sacred. Everything is alive. You’re creating it from moment to moment, even if you think you aren’t, you actually are. And so now I have a bit more grounding in those esoteric principles about the holographic nature of reality – and how it’s not a static thing. So now I can do a little bit more of an impeccable attitude, rather than a kind of under duress attitude, does that make sense?

RS Something like animism?

BC I’m of that tradition, I would say.

RS Can you say more about your near-death experience?

BC Well, at a certain point I tried to commit suicide. I took an overdose and went into a coma and it’s a miracle that I survived, apparently. And I just had this massive epiphany during the experience, and it had everything to do with the nature of time. There was some kind of ‘spiralised-transactional-pass’ event that took place. I don’t know if I got swapped out or something, but something… spiralised. I just basically realised that the universe is conscious, that I’m part of it. And so I sort of got shot out the other side, kind of born again.

RS As what?

BC Well, I would say I was probably brought up with a homegrown pagan-animist cosmology from my father, who was more of a space cadet, more of a Toltec than my mum, who was more of a staunch atheist, rationalist pragmatist. These would be the closest things I had to a model of the universe. So I was born again, not as a Christian, but as animist, I suppose.

RS And had the suicidal compulsion faded?

BC Gone! Gone!

Everyone’s an Artist

RS You said you were swapped –

BC I was swapped out in an instant from someone who wanted to die to someone who wanted to live. But really, someone who wants to die is not really someone who wants to die. They’re just someone who’s in a lot of pain and confusion, and they’re motivated to take a leap. I think it’s because I didn’t want to go mad. I knew I was going mad, but I didn’t have the courage to go mad. So, I chose. I was choosing death because I couldn’t stand being here anymore. I was very sensitive. I could feel the evil in things and I didn’t know how to protect myself from it. So yes, in an instant I went from that to just being on this massive quest. A Gnostic sort of quest. That was 25 years ago.

RS And it sounds like you feel as if you, in some ways, arrived at the end of your quest with that show.

BC I think you’re right. I think you’re right. A 25-year project.

RS Your contract with art, at that point, had been fulfilled.

BC Right. I mean, never say never, and the wider project is ongoing, but I feel that everything is changing and for one thing, every human will realise they are a born creator. So, the idea of an ‘artist’ in the professionalised sense, in the sense of an artist as ‘special case’, I think that will fizzle out. And all humans will realise that they are born creators, and therefore the meaning of ‘artist’ will change. So, I don’t know what the artworld, ie the gallery system, is going to do moving forward?

RS How you are inventing your life going forward?

BC I think it’s becoming more and more the case that my creative focus is primarily in psionic interaction with the rest of nature. Also, living off-grid is high maintenance, and meaningful physical hard work is very grounding. But at the moment I’m also having these telephone conversations with an artist who goes by the name ‘The Beat Messenger’ where we’re doing quite a lot of visioning and mining thereof. We think it’s highly likely that she may have been in these unacknowledged ‘MILAB’ [military abduction] programmes where gifted children were identified and tracked and taken off to the side and then involved in highly esoteric military research programmes.

And then I have this thing about the 200-acre wood next to our home off-grid in Cumbria. The forest was the primary metaphor for the mind before computers came along. And what I’m trying to do is to internalise a mental map of this particular forest, the topography of it. I wanna model that forest mentally without the use of pen and paper, but physically walking it. You can easily get lost in there; it’s undulating and rocky, ancient and intelligent.

RS You are building a kind of memory palace.

BC Yes. So, I want to model it but not in an exoteric/exterior way, only in an interior way. As a learning aid, for one thing. As a model for contemplating the nature of neural networks and the nature of thought. I want to go deep into what technology really means when it isn’t hijacked by…

RS Hardware?

BC Yes. There are subtler technologies of the mind we can work with, which is sort of what making an art object is anyway. It’s a mimicking of that potential. And so I wonder, if there’s no relegation to the sanctioned ‘artworld’, if there’s no gallery system, then what will artists be doing with the technology of their mind in nature?