Khalili’s ‘activation of history’ through film brings archival content into the present and commends it for the future

Around the time of the 2010–12 Arab uprisings, the artist Bouchra Khalili began developing a series of projects that address the histories of emancipation and liberation in North Africa and the Middle East. Taking issue with how Western media described the uprisings as a ‘Facebook Revolution’ – “as if the Arabs needed Facebook to start a revolution”, the artist pointed out in a 2017 conversation – Khalili realised the importance of asserting the region’s history as both revolutionary and global.

The video Garden Conversation (2014) illuminates that legacy by imagining a conversation between Rifian resistance leader Al Khattabi, who led a war against the French and Spanish colonial armies in Northern Morocco from 1921 to 1926, and Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara, who fought in the Cuban Revolution. According to oral accounts, the two men met in Cairo in 1959 but no documentation exists, so Khalili wrote a script based on their writings and interviews. Filmed in Melilla, a Spanish enclave in Northern Morocco whose continued existence signals the colonial spectre of occupation, a young Moroccan man and woman (neither of them trained actors) play Khattabi and Guevara respectively, and discuss tactics of liberation. “The present time is made of struggles,” the woman says, “but the future is ours.”

Khalili produced Foreign Office (2015) next. A digital video, silkscreen print and series of photographs focus on Algiers between 1962, when Algeria gained independence from France, and 1972, during which time the Algerian capital hosted liberation movements from around the world, including the Black Panther Party and the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde. In the film, two Algerian students, Ines and Fadi, narrate this moment of transnational solidarity based on oral accounts, texts, photographs and videos documenting the presence of figures like Nelson Mandela, who trained with the Algerian National Liberation Front, and Black Panthers Eldridge and Kathleen Cleaver, who attended the first Pan-African Cultural Festival in Algiers in 1969 and established the Panthers’ international branch in the city.

Black-and-white photographs of these figures, alongside others like Malcolm X, Frantz Fanon and Amílcar Cabral, are seen assembled on a wall at the film’s start. Towards its conclusion the narrators remove the pictures from an editing table, describing how the story of this historical moment ends: some died, others gave up, some were exiled, others became dictators. That scattering of figures and movements in all directions is grounded to the diagram that emerges when the film’s narrators mark the locations where these organisations were based on a map of Algiers, and in the photographs Khalili took of these colonial-era buildings in the present day. The silkscreen print The Archipelago (2015) distils each location into flat, white shapes arranged on a sky-blue ground, like islands in the sea – a metaphor, Khalili has said, for international solidarity, as people and movements find ways to connect their struggles not only across geographies and borders, but across time, context and language.

That archipelagic quality likewise reflects a creolisation and comingling of anti-imperialist movements in the twentieth century – from the establishment of the Non-Aligned and Anti-Apartheid movements to the development of political Blackness in postwar Britain – through their dissemination, as embodied in Mother Tongue (2012), the first in Khalili’s trilogy of films known as The Speeches Series (2012–13). Five migrants in Paris recite texts from memory by Aimé Césaire, Al Khattabi, Malcolm X, Mahmoud Darwish, Édouard Glissant and Patrick Chamoiseau. This includes Césaire’s 1950 text ‘Discourse on Colonialism’, which describes the West’s hypocritical inability to solve “the two major problems to which its existence has given rise” – “the problem of the proletariat and the colonial problem” – and the refuge it has taken “in a hypocrisy which is all the more odious because it is less and less likely to deceive”. That each person speaks in a language, with the exception of Dari, that has no written form – Moroccan Arabic, Kabyle, Malinke and Wolof – feeds into Khalili’s interest in history as an act of living transmission and translation: multilingual, subjective, collective, fluid, global.

As with all of Khalili’s films, the narrators in Foreign Office were nonprofessional actors who became involved in the project through their encounters and discussions with the artist. That Fadi and Ines were students, however, was a deliberate choice: a mechanism worked into the composition to both document and enact the transmission of a fading historical memory in Algeria to the next generation. ‘Fadi and Ines learned the historical details during the preparation phase of the film,’ Khalili told writer Thomas J. Lax in the book accompanying the project. By processing archival content as ‘living material’, the historical matrix of a scattered transnational, transcultural anti-imperialism ‘entered into their present.’

That activation of history – or as Khalili described it in the 2017 Creative Time Summit by quoting Pier Paolo Pasolini, ‘the scandalous revolutionary force of the past’– defines the artist’s interest in alternative historiographies. That is, histories expressed not by those in power, with their monuments and books, but by ‘poems, songs and even jokes that we share and that go back to our silent history of rebellion’, as she put it at the summit. Even The Mapping Journey Project (2008–11), an installation of eight videos, each showing a migrant’s hand tracing on a map the journey they took to enter Europe from Africa, the Middle East and South Asia with a pen, is an expression of resistance. Whether in relation to the borders that have divided the world as a result of colonial modernity; the obfuscations that have reduced migrant lives into voiceless numbers; or the asymmetrical geopolitics that have driven people to flee their homes in the first place.

Each journey recorded in The Mapping Journey Project is distilled into a silkscreen print composed of white, starlike dots on Prussian blue for The Constellations Series, the minimalist aesthetic of which turns each testimony into a point of transmissive reflection. In one case, a man’s meandering trailfrom Ramallah to East Jerusalem to see his fiancée – a journey that would have taken no more than 20 minutes by car had it not been for the restrictions on the movements of Palestinians – reflects both the conditions of internal displacement created by Israel’s military occupation and the force of love (for others, for life, for home, for freedom) to defy them.

The hand, a crucial motif in Khalili’s films, amplifies these scales of politically charged intimacy in the context of history as a surgical assemblage of narrative fragments – words, sounds, images, objects, memories. ‘A narrative is never raw. It is always produced,’ Khalili has said, and the artist makes that production coolly visible with documentary compositions shaped by the structural grid of an editing room and its materialist poetry, which includes scripts whose quotations and interjections function as testimonies of living history. As Khalili has noted, Jean-Luc Godard once said that he would choose to lose his eyes rather than his hands, since films are made with the fingers: ‘I think at least with regards to montage, this is absolutely true: when editing, it is the hand that thinks’. The hands handling materials in Khalili’s films draw viewers into the work of piecing together a multipolar and multiscalar story.

Take Mapping Journey, which responds to how migrants have been portrayed by Western media while resisting their erasure at home. Growing up in Casablanca, Khalili heard stories of people travelling illegally all the time, but they were discussed among the community rather than acknowledged by the media or state – people risking their lives to migrate illegally don’t just signal attempts to escape poverty but announce a political opposition. As Khalili has said, her conviction to return to the region’s history amid the Arab uprisings has not only been about decolonising narratives and representations in the West, but confronting the oppressive regimes that have been produced beyond it.

The Magic Lantern (2020–22) amplifies this multifaceted struggle. The video installation departs from the surviving images of The Nero of Amman, a film by Carole Roussopoulos that recorded the aftermath of Black September in 1970, a conflict between the US and Israeli-backed Jordanian army and the Palestine Liberation Organization, supported by Soviet-allied Syria and Iraq. The film, its print having been destroyed due to how frequently and widely it was screened, highlighted the dire situation of the Palestinian people in the immediate years after the establishment of the United Nations and the Israeli state, with refugees massacred and generations displaced. Roussopoulos critiqued these conditions in her later film Munich (1972), where the surviving images of The Nero of Amman appear, which confronted the UN’s international ‘peace’ in the context of the Munich Olympics, when the Black September militant organisation took Israeli delegates hostage, killing 11.

The Magic Lantern uses cinema’s alternative histories and functions to meditate on these geopolitical textures. The video installation is projected with an object modelled after the magic lantern, a protoprojector invented in the eighteenth century that Étienne-Gaspard Robert used to summon the spectral projections of executed French revolutionaries Maximilien Robespierre and Jean-Paul Marat, the film’s narrator explains, “at a time of collective mourning for a collapsed revolution”. Khalili connects the use of the magic lantern’s revolutionary technology for revolutionary purposes with the Portapak in the twentieth century, the first battery-operated individual analogue video camera-recorder that Roussopoulos and other radical filmmakers used, including to make The Nero of Amman. That film’s surviving shots are described in The Magic Lantern as spectral images, and their haunting depictions appear like a macabre resurrection today as devastating images from Palestine circulate once again.

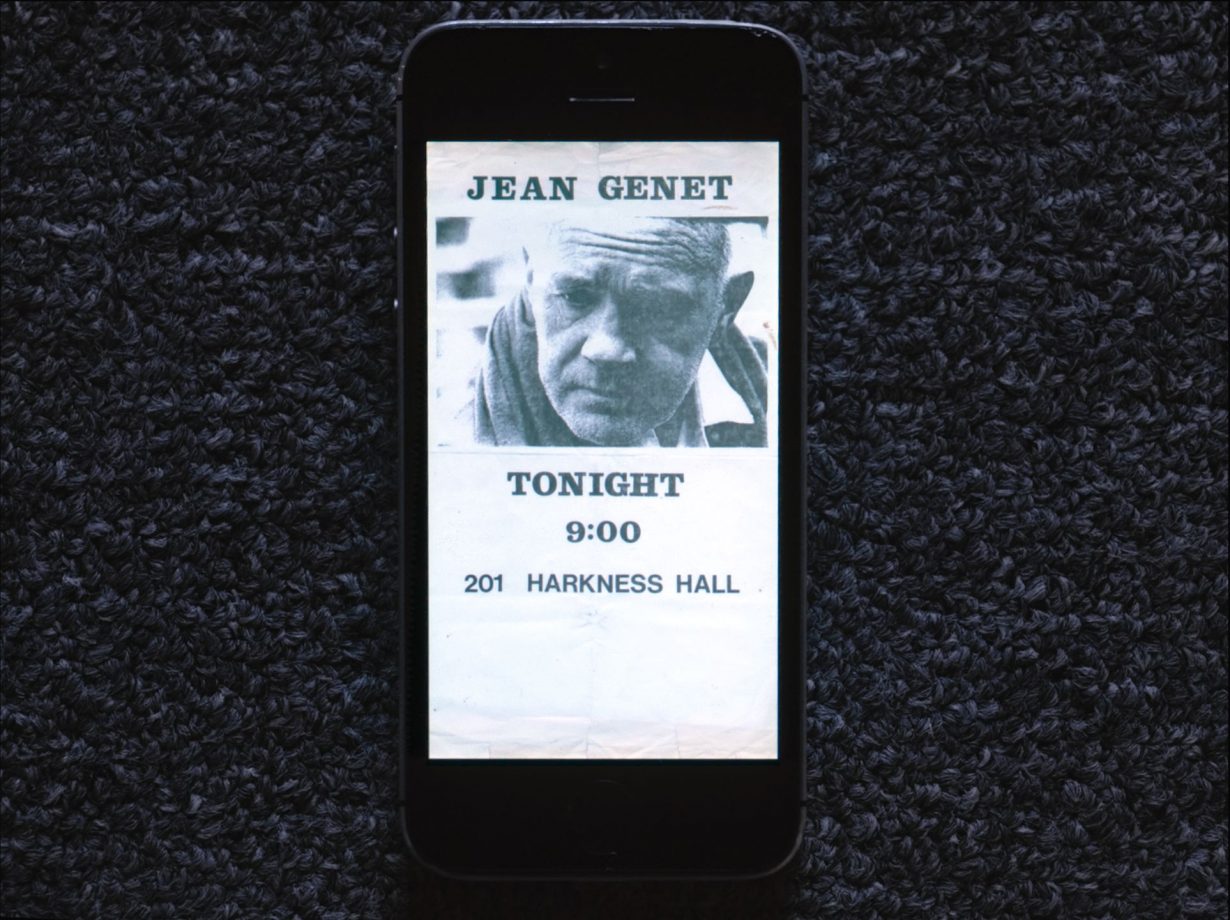

All of which relates to what Khalili describes as the recurring ghosts in her work: artists and allies like Roussopoulos, a radical filmmaker described in The Magic Lantern as a nomadic storyteller, and Jean Genet, at heart a revolutionary poet, who travelled together to Amman in 1970 alongside Mahmoud Hamchari, the French leader of the PLO. A vocal supporter of the Palestinian liberation movement, Genet was among the first to enter the Shatila refugee camp in Lebanon in 1982, just after Phalangist militiamen massacred Palestinian and Lebanese civilians under the light of the occupying Israeli army’s projectors and flares – an experience he documented in his 1984 essay ‘Four Hours in Shatila’ and in his final book, Prisoner of Love, published posthumously in 1986.

Khalili references Prisoner of Love in her 2018 video Twenty-Two Hours, focusing on Genet’s visit to America in 1970 at the invitation of the Black Panther Party, supporters of Palestinian liberation. The film’s title derives from Khalili calculating the time Genet spent with a young fedayeen named Hamza, leading Khalili to ask, as she put it in one interview: ‘Are twenty-two hours enough to dedicate oneself to the struggle of other people?’ The question feels rhetorical, given the meditation on solidarity that shapes Twenty-Two Hours, as its narrators, two young Black women named Quiana and Vanessa, process images on phone screens related to Genet’s American tour while reflecting on his allyship, and by association his gaze. “Why did he write about us?” they ask, with a script mixing quotations, notations, observations and questions.

Archival footage in the piece includes Genet, shot by Roussopoulos, denouncing Angela Davis’s incarceration and proclaiming that the ideas of Davis and the Black Panthers will remain long after those maintaining what he termed the “white administration” are gone. They combine with Khalili’s footage of Douglas Miranda, who describes his work with the Panthers, including the campaign for detained chairman Bobby Seale and party member Ericka Huggins, of which Genet’s May Day speech was a part. Wearing a black leather jacket from the Panthers, Genet spoke a few lines in French before information minister Elbert ‘Big Man’ Howard continued in English. The narrators describe a confused public, unable to decipher whose words were being spoken, before quoting lines from the text, which called for white radicals to act with “candour” and “delicacy” in relation to the Black struggle. “The identity of the speaker did not matter,” the narrators continue. “He offered his support, he offered his presence, he offered his image, and therefore he offered the words, abolishing any ownership over them.”

That abolition of ownership circles back to the histories of anti-imperialist struggle and transnational solidarity that Khalili maps out across her films, where historical fragments fuse into narrations anchored to the central question that Twenty-Two Hours poses: who is the witness? Khalili responds by creating a cinematic montage of witnesses across time: from Genet, “whose books speak for him”, and Miranda, “who can still speak”, to the narrators bearing witness now and their viewers tomorrow. Quiana and Vanessa perform that transtemporal encounter when they ask Miranda if the Panthers failed. “It’s a fair assessment… no shame in that,” he responds. “The fundamental nature of capitalism and white supremacy” – which includes “the extreme brutality, oppression and super exploitation of African Americans, other minorities and the American working class” – “still exists today… so we will bury our dead, learn our lessons and continue to move forward”.

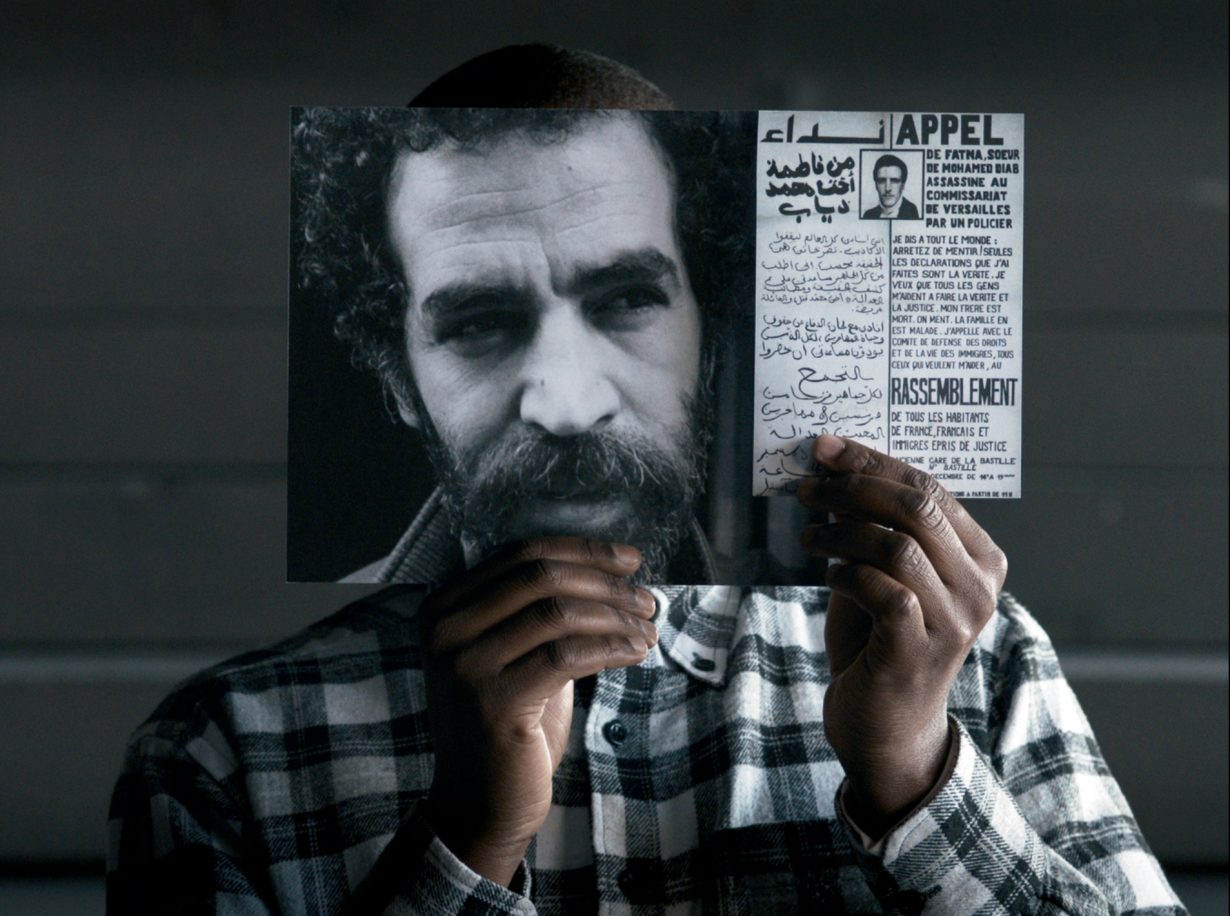

Cue the video The Tempest Society (2017), which resurrects the story of the agitprop theatre group Al-Assifa, or ‘The Tempest’ in Arabic, which operated in Paris from 1973 to 1978. Composed of North African factory workers, members of the Mouvement des Travailleurs Arabes (MTA) and French students, Al-Assifa staged performances in factories and public spaces that reflected experiences of oppression in France while responding to high levels of illiteracy among migrants. Khalili sees the tradition of Al Halqa, meaning ‘The Circle’, in their efforts, a public performance in Morocco where audiences form a ring around storytellers, which Khalili situates in the history of revolutionary art and cinema, where documentary, as the artist has described it, functions as a hypothesis: an ongoing question.

The more-recent two-channel video installation The Circle (2023), which excavates the MTA’s establishment in 1973 in Paris and Marseille alongside that of Al-Assifa and its sister theatrical group Al Halaka, also meaning ‘The Circle’, expands on that continuity. The work opens with the same gambit as The Tempest Society, with the latter’s three interlocutors discussing how to begin their narration – as a group or as separate individuals – before concluding that they want to tell a story together. A shot of hands arranging archival images on an editing table follows, as The Tempest Society narrators describe “a constellation of individuals, events, time and geography addressing the need for hope, the need for dignity and the need for equality”. They then take an online call with the narrators of The Circle, a young man and woman of Maghrebi descent living in Marseille tasked with extending the constellation of connections across years and cities in the present work: one of many projects shaped by research through which Khalili is mapping out another world history.

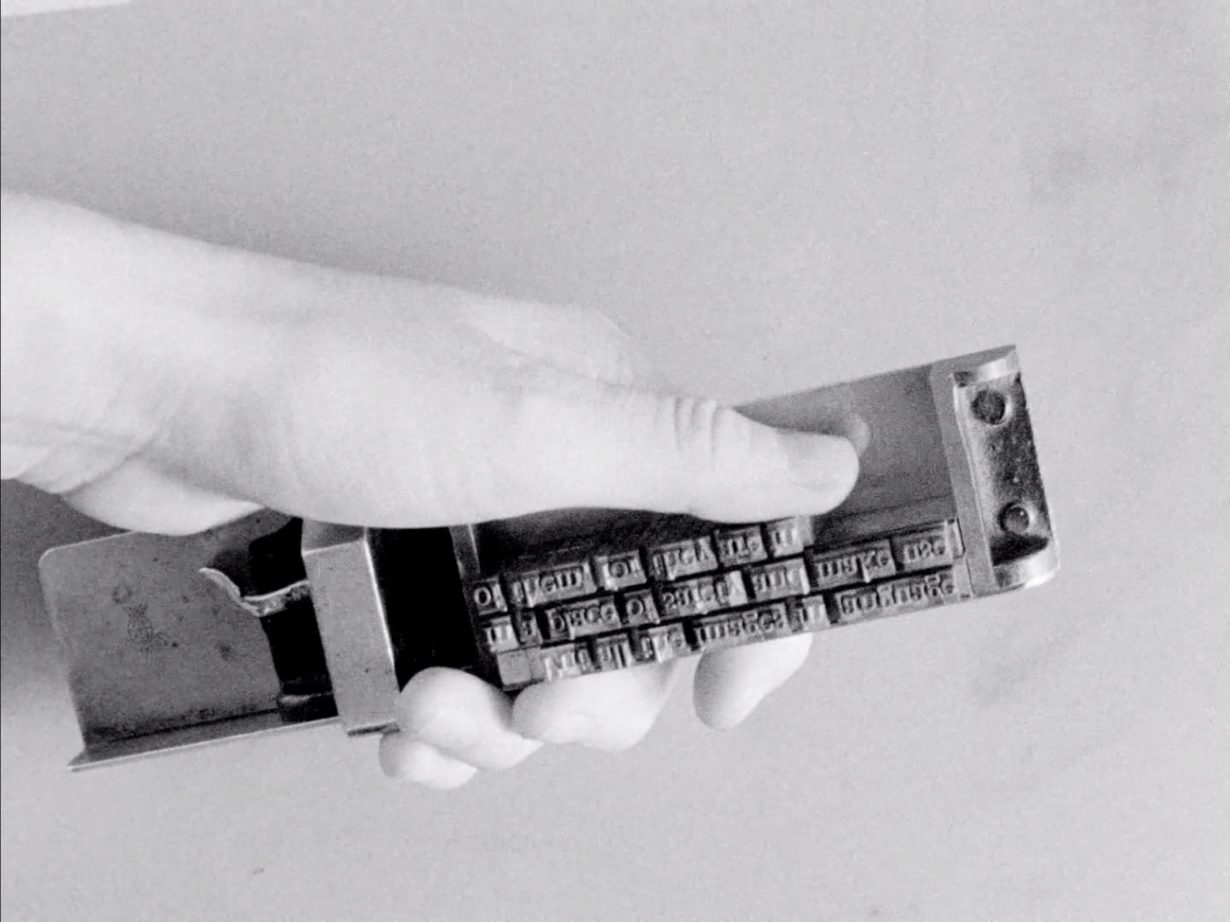

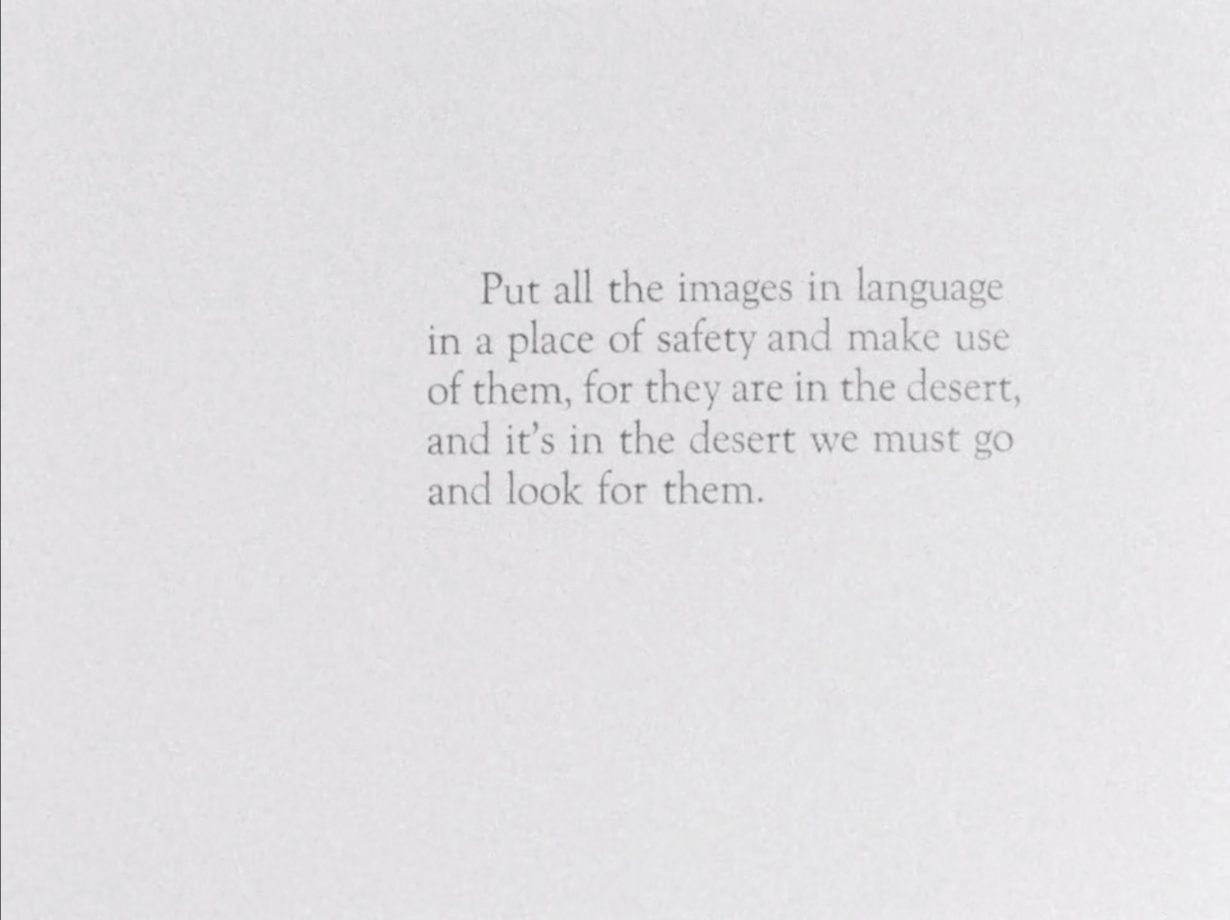

“Our family album is made by the struggles for equal rights here and elsewhere, today and tomorrow,” The Tempest Society’s narrators say: it “is essentially a collective: we don’t own it. It travels and expands.” The point, they explain, is to start from where and who you are: “What is this continuous chain of resistance across time, space and people?” Khalili’s black-and-white 16mm silent film The Typographer (2019) doesn’t offer an answer so much as open up a horizon where intersecting past, present and future revolutions meet. Here, hands are seen manually typesetting Jean Genet’s final sentence in Prisoner of Love, which reads like a message in a bottle: ‘Put all the images in language in a place of safety and make use of them, for they are in the desert, and it’s in the desert we must go and look for them.’

Bouchra Khalili: Between Circles and Constellations is on view at Sharjah Art Foundation, 7 September – 1 December. Khalili’s solo exhibition Lanternists and Typographers can be seen at EMST / National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens, through 10 November as part of the exhibition cycle What If Women Ruled the World? Khalili’s The Mapping Journey Project (2008–11) is being shown in Foreigners Everywhere, at the 60th Venice Biennale, through 24 November

Stephanie Bailey is a writer based in Hong Kong