Bruce Asbestos interviewed by Aaron Juneau

Artist Bruce Asbestos has lived and worked in Nottingham for the past 20 years. Through his shrewd use of social media, personal re-hashing of global pop culture and use of new digital technologies, he has established an unmistakable visual identity and unique brand (complete with logos) to almost become a ‘living artwork’.

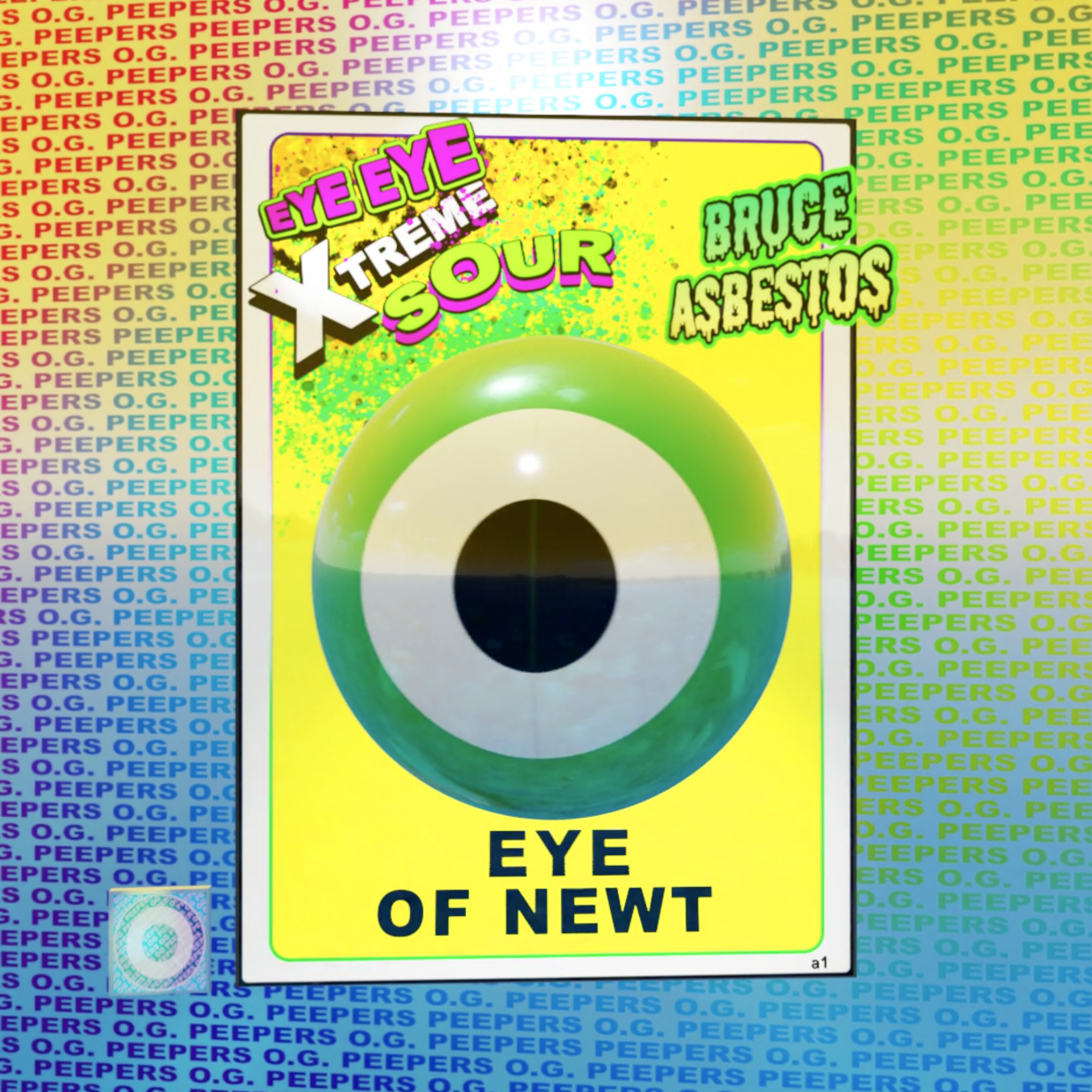

His artworks have included his own TV channel, catwalk fashion shows with bespoke collections both real and virtual, paintings of pop and cultural icons, a giant inflatable newt’s eye and, most recently, purchasable online artworks in the form of spinning orb ‘digital assets’ or NFTs. Recently, Aaron Juneau asked Asbestos about his influences, how he got his name, and what pandemic and lockdowns have meant for the appreciation of digital art…

Aaron Juneau Where did the name Bruce Asbestos come from?

Bruce Asbestos I changed my name on 3 March 2010. I was interested in the idea of a thing that is performed whether you are there or not. I liked the idea that a name could have this uncertainty about it, and that people in very boring bureaucratic jobs would perhaps have this moment of doubt whether the name was real, as the paperwork came across their desk, and that would be like a mini performance. I also liked this slightly tasteless idea that you could become a brand; I was interested in where that could take you, what doors it could open and what doors it would shut.

AJ There seems to be a certain ‘Bruce Asbestos filter’ that anything you come into contact with goes through. Things from the world go in, then come out ever so slightly ‘off’, a bit wonky, not quite as they should be – whether it be supersized, made from inappropriate, unexpected materials, or rendered digitally to allow otherwise impossible juxtapositions. What’s happening in this process?

BA I’m getting quicker at picking things to put together, the right technology or the right type of culture, in an unusual way. Art is life changed twice. I guess you’re always looking for the thing to be more than its component parts.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the word ‘participation’ this year and I think I’m always looking for opportunities to participate in culture and enjoy cultural ‘moments’ that come in many different forms. Sometimes it’s a more direct copy or interpretation and sometimes it goes left-field and you see where you end up when you sort of splice two things together. The catwalks are the most direct ‘splice’ I’ve done – performance and fashion together. I’m looking for moments of intensity in wider culture, not just in the space of contemporary art.

AJ You’ve had the opportunity to travel as part of your artistic research. Where have you been and how has it influenced your work?

BA Early on I had a scholarship to Japan in 2004 and I spent a good proportion of it wondering about Takashi Murakami’s output – he was absolutely everywhere then, on drinks, adverts, in galleries and shops. I was thinking what if it is just consumerism? Can this be interesting as art? Followed quickly by – does it matter? Does this make it worse, or even better? I was sort of in a loop – the more I despised the art, the more I ended up liking it. I liked its commercial abrasiveness, its vacuousness, but I also liked its possibility. If Murakami’s toys are subversive, then do they remain in art because they are differentiated from other products through their intention? If his work isn’t subversive is there anything to indicate its difference from the world?

I went back to Japan recently and the cute ‘Kawaii’ period is definitely over. You see this emergence of a much more bland, globalised and more Western sense of ‘beauty’ driving pop culture, which doesn’t seem as interesting. I liked the cute/Kawaii, because I could see its roots in the history of Ukiyo-e wood block prints and Manga.

AJ You’ve worked over the last few years with visual effects software, video games and digital renders and most recently NFTs… Why are you drawn to these things and what has your experience been of using them?

BA In the past year, I’ve used Blender, an open-source 3D computer graphics software, to ‘kill my darlings’. I just went to town, as if I had all the budget and all the space in the world, and made tonnes of hypothetical exhibitions. It was a great way to kill off some terrible ideas, and actually mentally prepare to make new works. The recent inflatables came out of this approach. The attraction is partly that you can iterate quickly and test out ideas, but also that these renders have a distinct quality in themselves. I prefer the Christo and Jeanne-Claude proposal drawings, to the real installations, for example.

AJ Your work could be described as ‘art for the social media age’ with social media playing a big part in forming your identity as an artist. Given that much of your work exists online or in the digital domain, how has it changed during lockdown and what do you think the lasting impact of the pandemic will be on your work and the work of others?

BA I’ve found it transformative, partly because it created a dramatic change in the way institutions work. I’ve found institutions have modified the way they acquire works of art, for instance. Whereas they might have relied on a few physical art fairs to access regional artists, they are now seeking out regional networks and individuals with expertise and knowledge of artists working there. I’ve got my first piece of digital work in a major collection partly because of this new process.

You can see museums scrambling to make whole teams for digital experiences now, it’s transforming the way galleries run, that they now think audiences online are as valuable or interesting as physical audiences. I think the move away from all cultural institutions occupying massive spaces is a good thing. This is much more reflective of our lives, isn’t it? Even pre-pandemic we were pretty much 50/50 in digital spaces, and there’s a huge market in video games already for virtual assets – clothes and the like. Why wouldn’t art reflect that?

It’s just forced a lot of things that were true anyway to be true from that institutional perspective – that where you live geographically as an artist is even less important than it was pre-pandemic, that there is a huge audience for digital artworks and experiences, that artists are less reliant and less attracted to the commercial gallery system, and that artists are having direct interactions with audiences through social media.

I’m as excited to sell a pair of socks with crocodile teeth on as I am to have an exhibition. I love that there are now more and more ways for all types of people to participate in art, from the heavily serious and profoundly conceptual, to the more fun and breezy interactions via keyrings, inflatables, cute Renders or collectible NFTs.

Bruce Asbestos will be participating in Plymouth Contemporary 2021, 7 July – 5 September

This article is part of Remark, a new platform for art writing in the East Midlands by ArtReview in collaboration with BACKLIT. Read more here and sign up for the Remark newsletter here