Nelson’s novel – a love story, set in South London – encourages a peculiar solidarity between narrator and reader

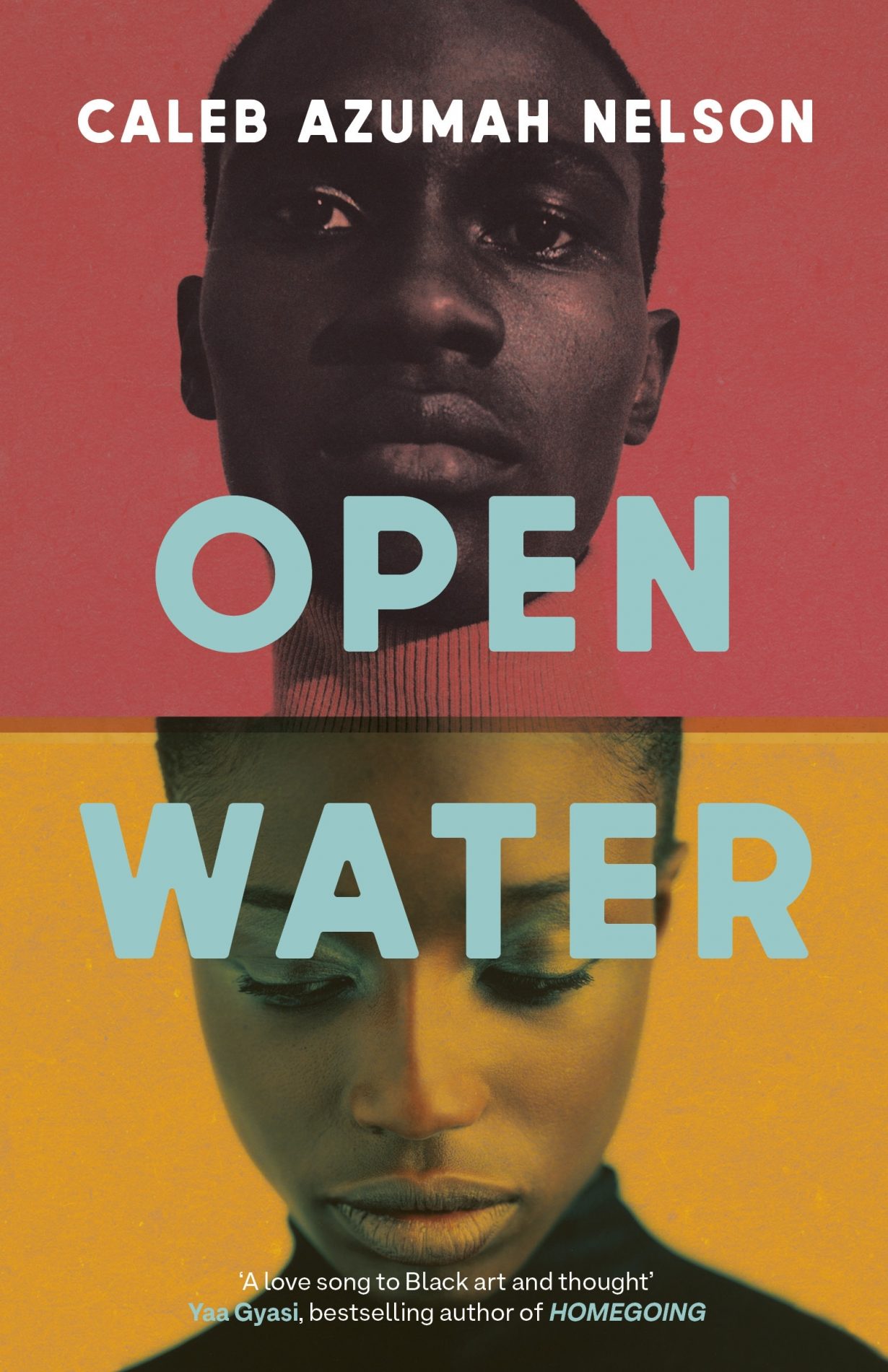

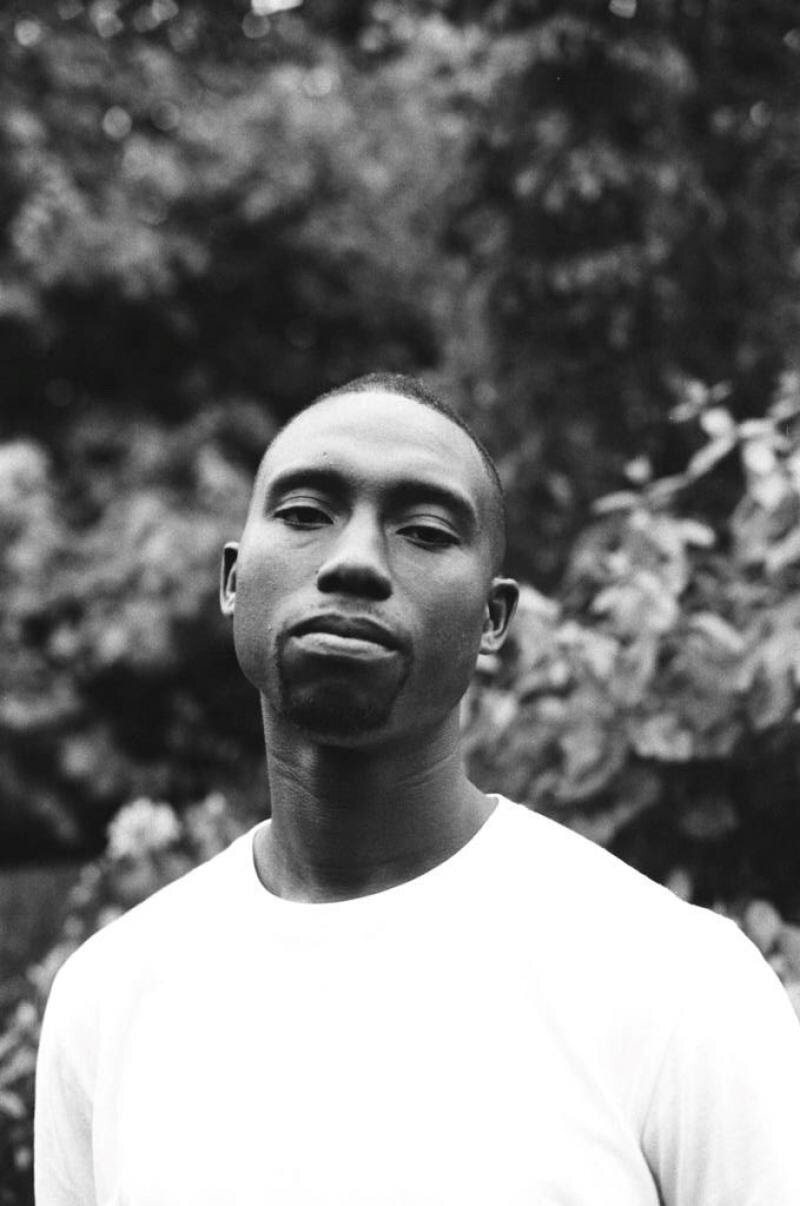

Caleb Azumah Nelson is a writer and photographer. Open Water, his first novel, is a tale about seeing and being seen. It takes the form of a love story, set in South London, involving a young male photographer (the narrator) and a young female dancer. Two people; two Black bodies. The one accustomed to observing other bodies; the other to expressing themselves through their body. The perfect union. Or so you’d think.

‘I know I’m a photographer, but if someone else says I’m that, it changes things, because what they think of me isn’t what I think about me,’ says the main protagonist when the couple first meet. From the beginning, then, he admits to an antagonism between how he sees himself and how other people see him. What follows is a (mostly) gentle unravelling of the conditions (generally the product of power structures) that have combined to create this fugitive identity. You are not your body, but your body is you to most other people. Particularly if your body is Black. Love, of course, presents an opportunity to, if not quite reconcile, then feel more comfortable with the gap between the two.

While this short novel, which nevertheless covers everything from takeaway choices to contemporary art and inspirational academic screeds, is told from a first-person perspective, the narrator is most often the object, rather than the subject of the tale, referring to himself as both ‘you’ and ‘I’. ‘I’ in direct speech, or in intimate moments (when the narrator dances: ‘I make a little world for myself, and I live’); but most often ‘you’, when experiencing everything from simply walking down a street to the randomness and brutality of police stop-and-search tactics. On the one hand, the ambiguity between the singular and collective ‘you’ reflects the way in which cities like London view Black identity. On the other, it encourages a peculiar solidarity between narrator and reader. It’s a kind of schizophrenia boiled down to a possessive pronoun – a fusion of form and content that Nelson deploys with a great deal of skill. And there’s no little irony in the fact that what lies at the heart of the problem for the narrator, this fugitive, unseen self, is precisely what provides space for the reader to jump in, to experience a little of what it might be like to be young, creative, male, British and Black.