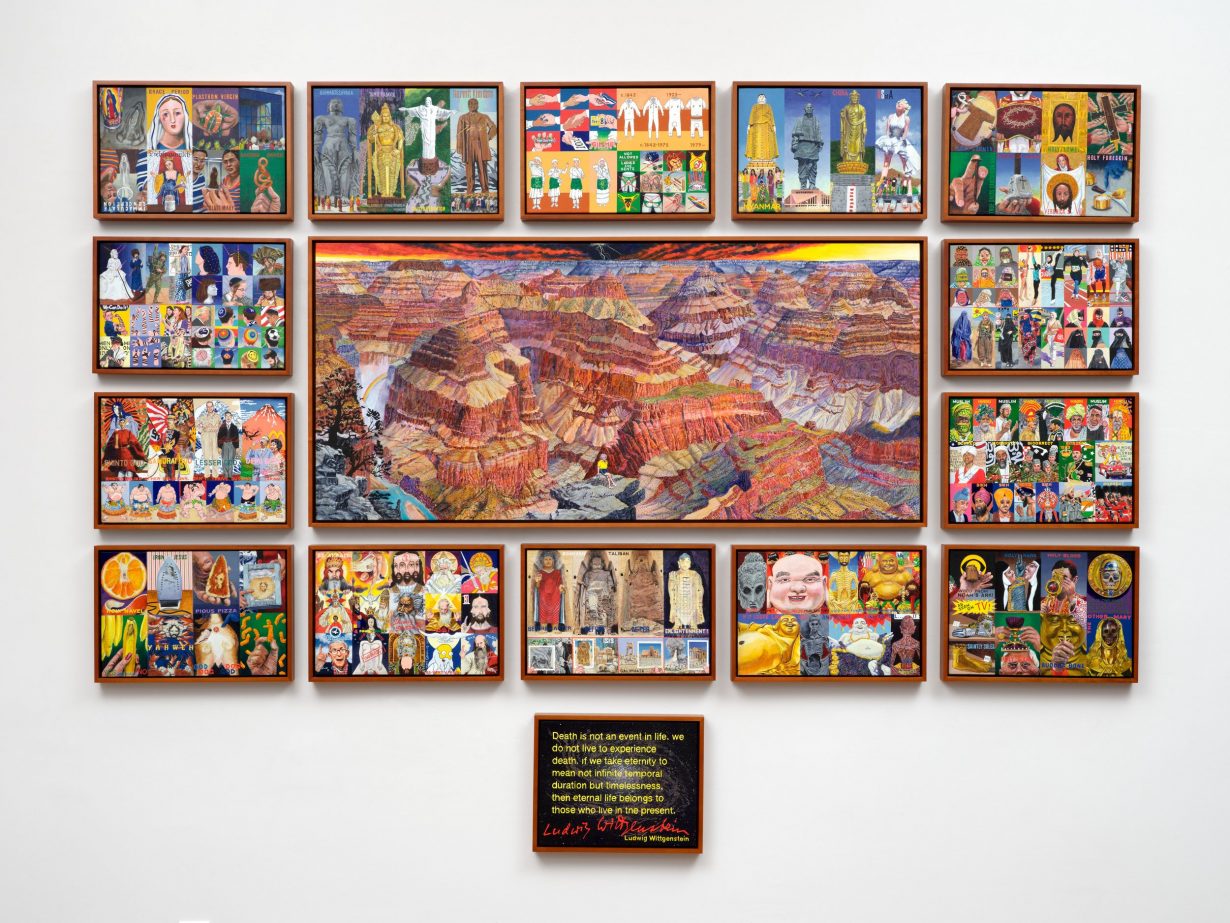

The California Biennial is embroiled in a censorship scandal after it accepted then rejected the work of 84-year-old artist Ben Sakoguchi just a month away from the exhibition’s opening. In a timeline provided by Sakoguchi, the artist says his work Comparative Religions 101 (2014–2019), a sixteen panel installation of paintings which satirically plays with images of religion, was chosen to be included in the show in June.

Sakoguchi says he signed the loan forms and arranged for the work to be shipped from his studio in Pasadena to the Orange County Museum of Art, the organisers of the biennial exhibition. Meanwhile, however, he claims he heard from the museum’s chief curator, Courtenay Finn, that concerns had been raised from within the education department of the institution.

The artist, whose work has previously tackled questions of slavery and the internment of Japanese-Americans, following his own childhood imprisonment in America, was then asked to record answers for a series of questions about the paintings, probing the imagery which the museum thought might make some visitors ‘uncomfortable, upset, triggered’.

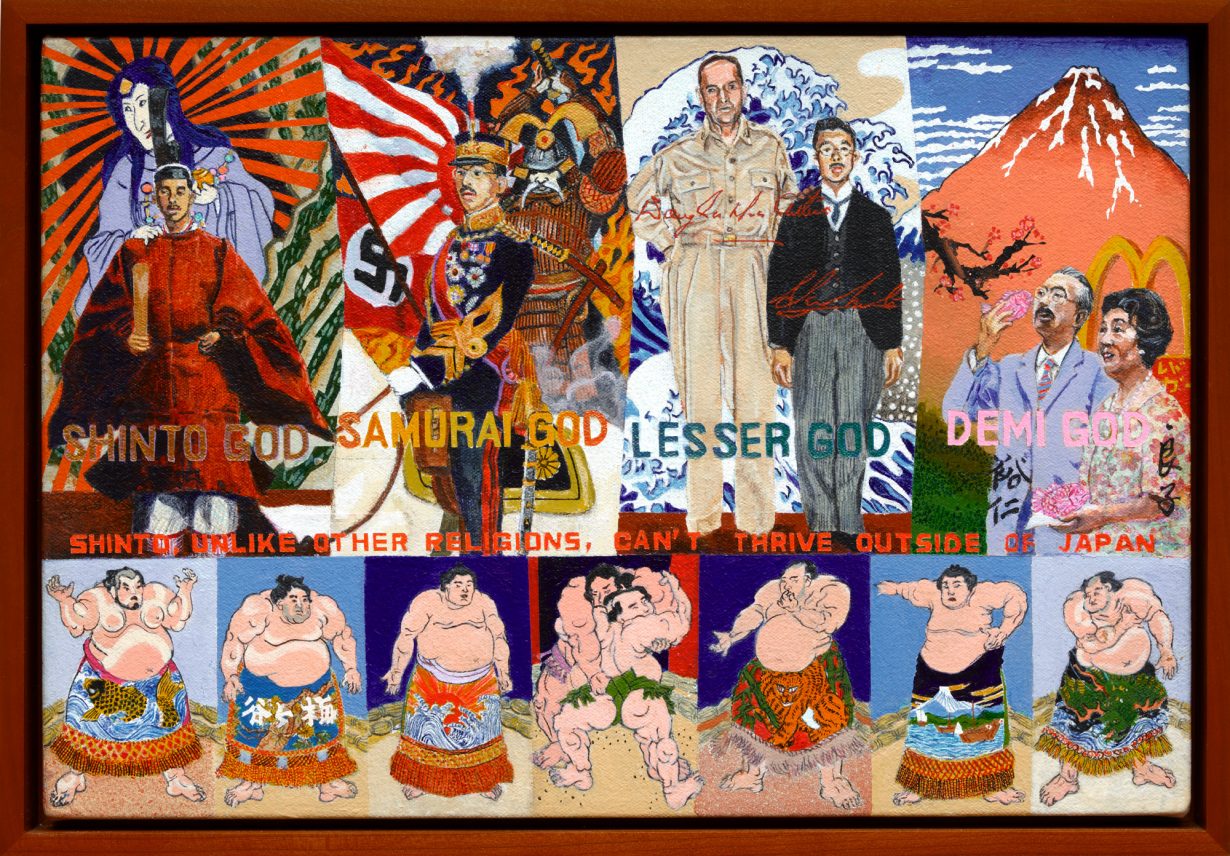

Two days after submitting his answers, along with an array of teaching aides and slide presentations concerning the depth of his work, Sakoguchi was told that the biennial could not exhibit Comparative Regions 101 because of one instance of a partially concealed swastika on a flag held by Japanese wartime emperor Hirohito, who was allied with Hitler’s Third Reich; and a second showing the symbol, again on a flag flying alongside a legion of Indian students who fought with Germany during the Second World War.

The artist says he also sent material concerning the religious use of the symbol.

Writing in ArtReview in 2021, critic Patrick J. Read, asked: ‘Even at one’s most vigilant, is it possible to acknowledge every iniquity, to trace every filament of systemic racism? The work of Ben Sakoguchi attempts to do just that. For the better part of 50 years, he has itemised social injustices plaguing the modern world in episodic paintings.’

The biennial, which dates back to 1984, and which the museum says has ‘defined the spirit of the institution for decades’, is this year titled ‘Pacific Gold’. It will feature 19 artists from across the state and is organised by former OCMA curator Elizabeth Armstrong – who curated the California Biennial in 2002, 2004, and 2006 – with Essence Harden, a curator at the California African American Museum, and Gilbert Vicario, chief curator at the Phoenix Art Museum.

Sakoguchi says the curators later tried to secure a replacement work without his permission, which was rejected. When asked to comment, OCMA told ArtReview the following statement: “Organizing the Biennial was an iterative process, with artworks being considered throughout the process, up until the opening. Ultimately the artist was not included in the exhibition.”

On his website the artist later provided the answers he sent to the museum, two of which are reproduced below:

‘Your work sometimes incorporates xenophobic, violent, and racist symbols, imagery, and language as part of its compositions. What are your thoughts on the current discourse around how the reproduction or continued representation of this imagery and language contributes to continued violence, harm and/or negative stereotypes?’

‘I’ve been on the receiving end of xenophobia and racism for most of my existence, and have lived though a long period of time where continued violence, harm and negative stereotypes were widely tolerated and swept under the rug. I favor selectively shining a light on the offending symbols, imagery, and language, both past and present, as a reminder of our history and of how far we still have to go as a society…and of how vigilant we need to be.’

‘Some of the visual elements and language in your work can be read as provocative and even inflammatory for the general public. How might you advise the museum to address an audience member who is uncomfortable, upset, triggered, or angry as a reaction to some of the language and/or imagery in your work?’

‘I have no advice for the museum in that regard. I’ve never believed my role as an artist was to make work that ensured comfort. My paintings are purposefully subject to alternate interpretations, and a reading of Comparative Religions 101 that provokes anger is certainly possible if the viewer is a literalist. But I can’t explain the humor and irony in the work to a literalist, any more than I can explain Red to a person who is (red/green) colorblind.’