The practices of both art and medicine rely on people asking the right questions. So, might the challenges offered when trying to decipher artworks have a relation to those encountered during medical diagnosis? A physician presents the case

You’re a young physician on a nightshift. You’re admitting patients, taking their histories. Now dawn has broken. You’re tired, exhausted, but you must tell your bosses on the ward round about the new cases. You crowd around a specific patient’s bed. You read the notes that you’ve written: ‘This man was complaining of chest pain going down his left arm and so I diagnosed new onset angina.’ Your boss asks the patient to go through his story again. You’re gobsmacked when the man says he hasn’t got any chest pain. He’s got a tummy ache. You’ve got it wrong; wasted everyone’s time. Was it your fault for taking a poor history? Has the patient had a change of symptoms or a change of their description? Or should that last bit be the other way around?

The mutability of truth is an everyday experience for physicians. As a former doctor, I’ve often wondered whether or not certain artworks might facilitate improvements in healthcare and medical education. In particular I’ve been thinking about whether video art might prepare medical workers for challenges like the one above. So, here are three zones of clinical expertise and three examples (among many) in which work by video artists could have a significant impact on healthcare practice.

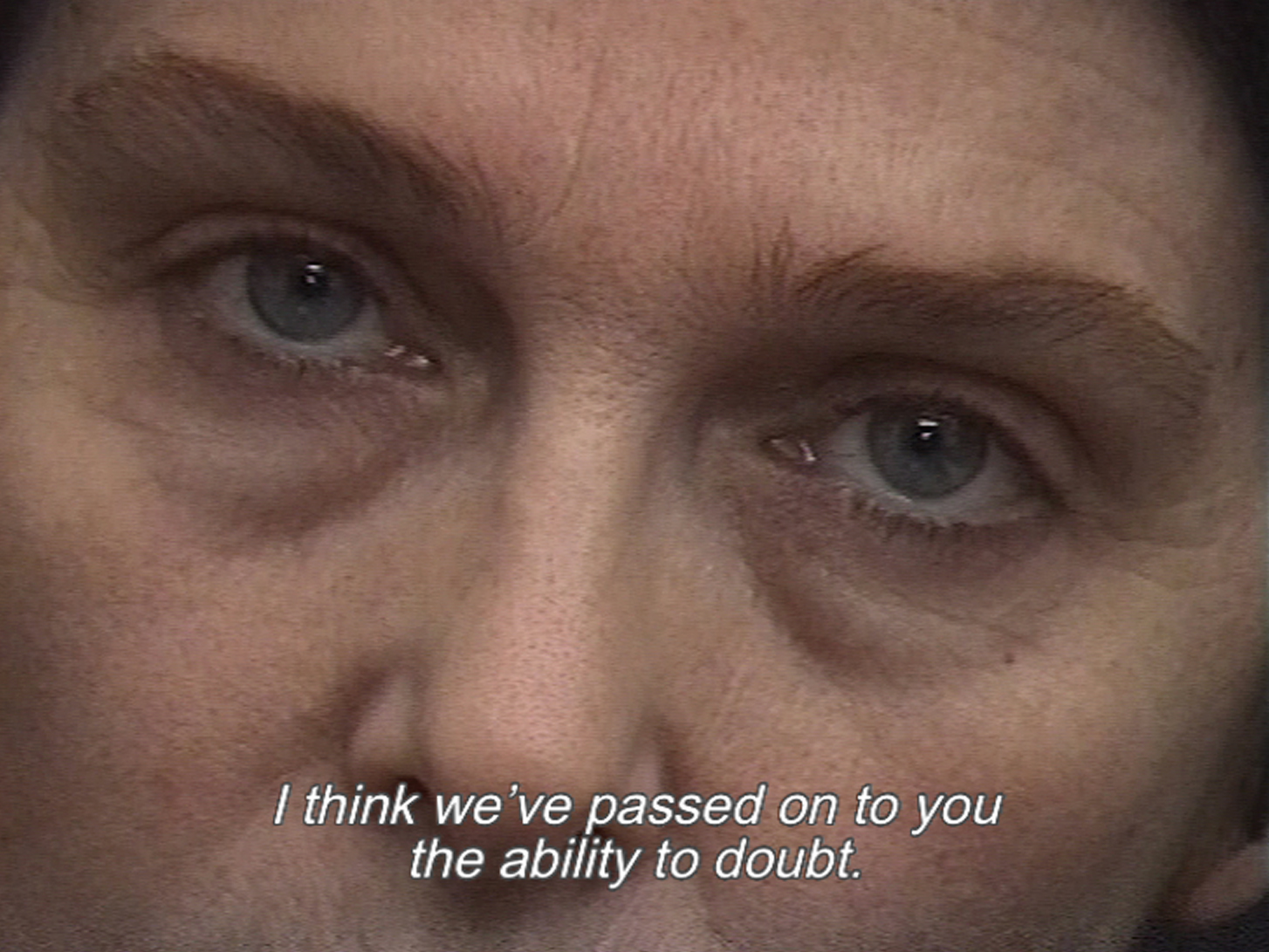

Communication skills are key to exemplary healthcare. Anri Sala’s Intervista (Finding the Words) (1998) is a work that might prepare carers for inconsistencies and denial. The work is about Anri’s mother, Valdet. In it, she is confronted with film footage of herself recorded many years earlier in Albania, during the Communist regime of Enver Hoxha. She’s reading subtitles of what she said at the time and she’s incredulous – “I don’t believe this”. As with our patient with chest pain, she’s changed her history: “I never said that!”

‘Unreliable historian’: a phrase used regularly by doctors on ward rounds to describe patients. As one former boss of mine had it, the real unreliable historian is usually the person taking the history. Valdet concludes Sala’s video by saying that she thinks we “should always question the truth”: a credo relevant to both artistic and medical practice. Healthcare workers must challenge ‘truths’ if the evidence base is weak. Informed scepticism is essential to the scientific method: we have seen too many disasters in medicine (birth defects as a result of thalidomide treatment, the Oxycontin misuse scandal, the recent conviction of British nurse Lucy Letby for murdering several babies) that occur because healthcare workers and managers have not asked enough questions. Sala’s video is a powerful tool to teach carers about the sheer insidious power of denial.

More obviously, there are several artists making videoworks that relate to specific diseases. To pick just one specialty – like neurology – there are those that deal with common illnesses, such as stroke, and others addressing much rarer conditions. The latter works are potentially helpful in medical teaching given the fact that trainees may wait decades to directly encounter such cases. Christine Borland’s Endless Walk (1999) is one such work.

Here an animated video is projected onto screens in two corners of an otherwise empty room. Most of the time the screens are blank, and then suddenly a young figure is seen slowly crawling from the side of one of the screens to the other. The figure disappears only to reappear on the screen in the opposite corner. The child is not a toddler, they are much older. The crawl is not normal: bent over, they use their hands to pull up and move their feet. The duration of this ‘walk’ is accentuated, deliberately stressed for our observation. This is known as Gowers’s sign and it’s how a child with Duchenne muscular dystrophy ‘walks’. For carers, this video illustrates – graphically – the serious impact of this disability, making you see and sit with the problem, rather than imagining it from a textbook description.

Another genetic inherited disorder with neurological sequelae is myotonic dystrophy, a condition that leads to muscle weakness and wasting. This has been the subject of work by Jacqueline Donachie. The condition affects her immediate family: her sister and brother have it – she does not. In Hazel (2015) we see a split screen with other affected families; five sets of siblings in all – one has inherited the gene, the other has not. The work stresses the diversity of the condition, as well as identity issues regarding altered facial appearance. Geneticists caring for those patients have documented their admiration for this aspect of the work – thus we have a definitive example of an artwork influencing carers themselves.

Erik van Lieshout’s video portrait of a fellow artist, René Daniëls (2021), focuses on a much more common neurological condition, someone suffering from a cerebrovascular accident (CVA) or stroke. Daniëls has been left with a severe expressive dysphasia but he still paints. The two artists have an unusual form of communication that revolves around Daniëls answering Lieshout’s sometimes complicated and subtle questioning about painting with only the words ‘yes’ and ‘no’. Van Lieshout’s patience, his lack of sentimentality, are a model of interaction that stroke carers would do well to study closely, given its deep insights into the empathy required for optimal management of patients. Also featuring Marleen Gijsen, Daniëls’s then-girlfriend and now-carer, the video gives us a fine example of post-CVA management at home.

My last example of the potential use of video art in healthcare focuses on the amelioration of stigma. Stigma, as social psychologist Erving Goffman underlines, is encountered everywhere in medicine, in those with ill health and those with physical deformity. One Canadian study has looked at the impact of watching an educational video made by people with mental illness, which helped create a more positive attitude in viewers, providing scientific evidence that videos can improve empathy scores in carers and in the general public.

In Candice Breitz’s Love Story (2016) we hear the testimonies of six refugees on six separate video screens all stigmatised in various ways. In a neighbouring room the actors Alec Baldwin and Julianne Moore alternately ‘act’ out the words of the refugees. The verbal tone and facial expressions of the actors are deliberately heightened and dramatised, in contrast to the more deadpan nontheatrical presentations by the refugees. The work asks if actorly reenactment and manipulation is more effective at inspiring empathy than the real account by the refugee. And in turn might this undermine or perpetuate stigmatisation? We hypothesise that a formal scientific study of the impact of watching Breitz’s work on carers might replicate the results of the Canadian paper.

These are only three topics where video art may help inform carers. At Brighton and Sussex Medical School we are setting up a module to enable undergraduates to study video art available on social media. Access will be predominantly via YouTube and other online outlets, but museum visits will also be included. The aim of the module is for students to acquire an interest in contemporary video art, with the hope that some may be inspired to engage in further academic study on its potential benefits in improving healthcare and in the development of video as both educational tool and art form. I’ll keep you posted as the programme develops.

John Quin is a writer based in Brighton and Berlin. For more than three decades he was an NHS physician specialising in endocrinology