The Qatar diplomatic crisis recently ended with a grudging rapprochement with its Gulf neighbours. Still, the impasse did provoke a groundswell of crossborder fraternal feelings, and a renewed interest in Khaleeji, or Gulf citizen identity. The photo exhibition Khaleejiness brings together 12 (very) young artists making work on the subject. It is organised by UAE-based publishing collective swalif and was prompted by a concurrently released book of photos and essays, Encapsulation Volume One. What a time to be alive in the Gulf.

The show opens with a section on the city and the desert. We know this because there is a tall vitrine half-filled with sand. Inside, against its back wall, are four large double exposures from Emirati Shamsa Al Mansoori, in which a woman in white flits around in front of some rather lovely old metal gates. Nearby, some sepia-toned collages by Qatari Hamad Al-Fayhani also superimpose the body onto the city, but here low aerial views replace street scenes. The figures are headless, but the effect is less Acéphale and more malfunctioning Zoom background.

A second, larger gallery focuses on more intimate, interior feelings. Its exhibition design is inspired by Omani photographer Abdulaziz Abdulah Alhosni’s photo Nadi Al Habayeb (2020) (not on view). To enter, you pass through a panelled telephone-booth door into a hot-pink-lit vestibule with rotary handsets dangling from the ceiling, which curator Sarah Al Mheiri tells The National is inspired by the older generation’s favoured mode of courtship, reading poetry to each other over the phone. The back of the door is covered in tagged scribbles, which range from initials in hearts and YT/IG self-promo to messages like ‘Eternal unconditional love For the Khaleeji Youth, Visionaries of the Collective’ and ‘simp free zone’.

The large space features pumping Khaleeji music, fuchsia-lit aubergine walls and a mauve-carpeted floor, a departure from the soft pink and blue pastels of Alhosni’s photograph. It is broken up by several seating areas consisting of patterned area rugs, coffee tables and colourful embroidered cushions. One corner is lined with shelves scattered with bottles. Upon buying your ticket outside, you are handed a small bottle containing a slip of brown paper tied with twine. Why? Because “Khaleejis aren’t good at expressing emotions”, I am told by the desk person; visitors are asked to write a “message of love” on the paper, stuff it into the bottle and add it to this installation. A placard on the tables seems to suggest that the work is by Alhosni, eliding the fact that it’s rather the curator’s experiential interpretation. Misleading, but a remarkably Khaleeji move all the same, except here it’s the state that operates as curator, instrumentalising artists into its own total artwork.

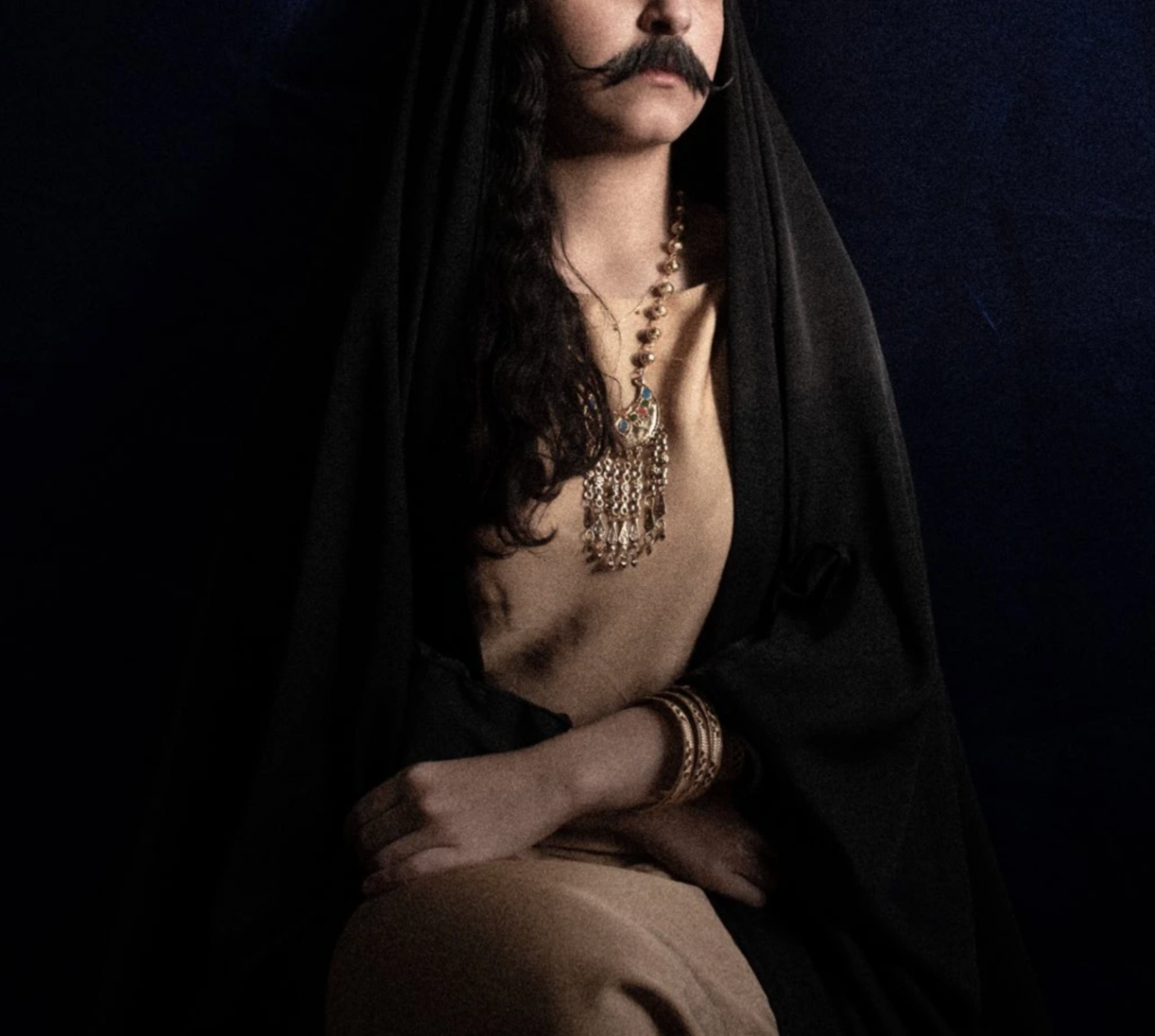

The works installed in this gallery offer a Khaleejiness that feels softer, more gender-fluid and, above all, extremely Gen Z. The better works have a dynamic fashion-photography feel, such as Omani photographer Mahmood Al Zadjali’s portraits of Balooshi culture, or Khaleejis with ancestry from the Balochistan region. In Saudi artist Khaldoun Khelaifi’s The Protector (2021), a man wears a pinstripe jacket and ghutra, whose characteristic red and/or white patterning is cast in a rainbow gradient. His hands cover his eyes, with evil eyes painted onto the nail beds; below the image, a hot pink phonograph crackles with dead air. Khaleeji identity has historically been a richly woven tapestry of language, culture and tribal-familial connections that long predate the establishment of its nations. With time, the state replaced tribal structures as the definers – and regulators – of identity. Each generation had its shared experiences: eking a living from unforgiving land and sea; the 1958 discovery of oil and breakneck, if asymmetric paces of development in the following decades; the Gulf War and the endless mediation of the 1990s that resulted in Gulf Futurism; and now, especially in the UAE, Qatar and Kuwait, how to negotiate being a demographic minority (albeit a powerful and privileged one) in countries primarily populated by people who hold other passports.

The book, to be fair, does include contributions from other Arabs and South Asians alongside earnest, if lightly edited pieces of personal writing. On view here however in the nation’s capital is a smaller selection that is limited to bona fide citizens of the Gulf. The show’s overproduction, all blown-up images, italicised quotes and awkward experiential add-ons, does these very young artists a disservice. QR codes that link to each artist’s Instagram make plain that this is not a collection of work so much as of people. I wonder how much better the show might fare in a pared-back project-space setting or just installed at a more human scale. But perhaps that’s forcing an exhibition-reading on what is first and foremost a branding exercise.

To be a Khaleeji artist today is to be conscripted into a chimeric, too-big-to-fail machine where soft power meets cultural tourism and national identity. Some artists navigate it admirably, making work with the same rigour that they did in the decades before the consultants flew in and assured leaders that, yes, these new institutions and mammoth international art events absolutely would scale. Many others fall victim to the arrested development that’s the result of artists being materially – but rarely discursively, critically – supported and pushed onto large institutional and international stages in what feels like a fundamental misapplication of scale. I want to believe that the same won’t befall this younger generation. But this show, despite an enticing premise, is deeply discouraging.

Khaleejiness at Manarat Al Saadiyat, Abu Dhabi, 31 August – 10 February