Johanna Hedva’s Your Love Is Not Good takes aim at creative ambivalence, flimsy niceties and facile attempts to be political

Your Love Is Not Good is three books in one. On the surface it’s an emotional and artistic bildungsroman: a journey of an ambivalently obedient artworld adept who has the MFA, a gallery who supports her, a series of shows in LA and Berlin to work towards, and the hand-wringing journey out of that, towards some kind of self-acceptance. But in its intimate mapping of the vicissitudes and dealings of her art professional arc, it’s also a handy guidebook of sorts, filled with apt perceptions and accurate barbs. Through which it also functions as a pretty accurate artworld satire and morality play, warning those who might wish to walk a similar path.

This is fiction, but it hews close to life: the eager gallerists, flippant curators and vapid artists who slip in and out of its pages feel like transcriptions from actual encounters rather than fabrications. The unnamed narrator (we’re told once only that her name sounds ‘almost’ like Hanne) is, like the author, mixed-race Korean-American and identifies as queer. But while Hedva is a writer, musician and artist, our first-person narrator is a self- conscious, self-effacing painter who seems to mostly deal in portraiture. As if immersed in her canvas-soaked mind, the staccato chapters of the book each are titled after various painterly techniques, with an accompanying short definition: pentimento, trompe l’oeil, impasto, craquelure. We jump from her past (growing up with a mercurial, abusive artist mother) through the arc of her art career. The writing is immersed in small details, skipping and impatient, filled with asides that feel like pointed commentary on artworld hierarchies: the awkward ‘courtship’ of professional relationships, ‘like a painting, is a trick of surfaces’; one character quips, ‘Since gallerists never have a life of their own, some of them actually think their artists are their friends… It’s like a queen who calls her maid her best friend.’ The text is imbued with a sense of psychological slippage and dread, the protagonist constantly finding lookalikes and twins onto whom she might attach a sense of self; while throughout the book, such as in the middle of a passage relating to a gallerist, will be an ominous non sequitur of a factual paragraph on an artist who died by suicide, for example Sonja Sekula, Arshile Gorky and Constance Mayer.

We follow as the painter takes on a model for a new body of work: a white trust-fund dilettante who possesses the ‘trust in herself that I’d never had. It was trusting gravity to never fail.’ The resulting paintings are a hit. Aiming to ride the wave to gain the artworld recognition she’s always been taught to want, she is waylaid by a performance artist who calls for nonwhite artists to boycott commercial galleries, fairs and museums. The painterly chapter-titles start to repeat and their definitions start to get mixed up – signposts for the painter’s spiralling state of mind – as she questions her work and where she stands in relation to the unambiguous ‘we’ that the boycott demands. While at times the book is overindulgent in its trite artworld bitchiness, its movements through the perceptions and impositions of race, from attempts at various forms of strategic withdrawal to the book’s anticlimax of (no spoilers) a ‘white girl being a white girl’, give the book a humming currency.

The ‘your’ of the book’s title levels an accusation that keeps us guessing: it might refer to one of the series of artist-dude hookups; or the self-possessed female artists with which the protagonist becomes hopelessly obsessed; or the mother who haunts her memories at every turn; or the diffident, self-destructive protagonist herself. Among its archetypes and excesses, and its portrayal of the artworld’s flimsy niceties and facile attempts to be political, it feels like it’s the artworld (and perhaps the reader, depending on where you sit within that) that might ultimately be the ‘you’. How, Hedva wryly asks, do you set about trying to make it better?

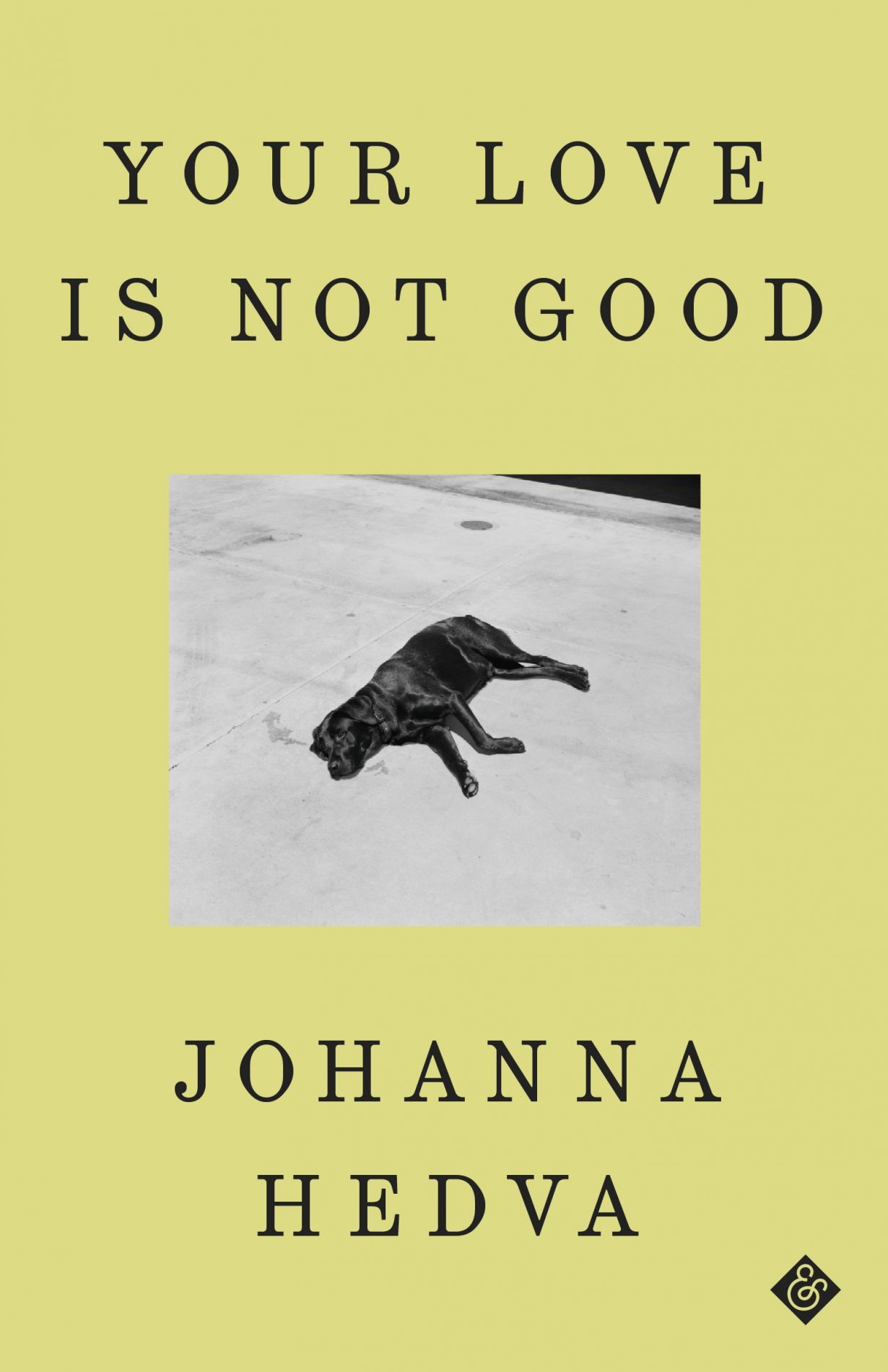

Your Love Is Not Good by Johanna Hedva. And Other Stories, £16.99 (hardcover)