The artist’s Serpentine Pavilion calls to mind another fire-blackened building in London

In the throes of a recession, a cost-of-living crisis, reeling from Brexit and with a government refusing to add £20 a week to an already stringent welfare package, Britain is a notable site for an offering of public art by the artist Theaster Gates, who has made his name through his work in the South Side of Chicago. Gates – who began his career as a potter, acquired a degree in urban planning and gained the eye of the artworld as a conceptual artist – runs a number of projects that aim to bring arts and economic opportunity to working-class and poor Black Chicagoans. For years, he has purchased dilapidated buildings and repurposed them as cultural centres as part of his preoccupation with economic regeneration and creating “spaces where ecstasy might happen” – sometimes funding his renovations by selling work on an art market that by turns fetishises and makes charity of poverty. At other times, Gates has castigated art fairs and other artworld institutions that both claim to ‘bring people together’ while chasing profits and greater influence.

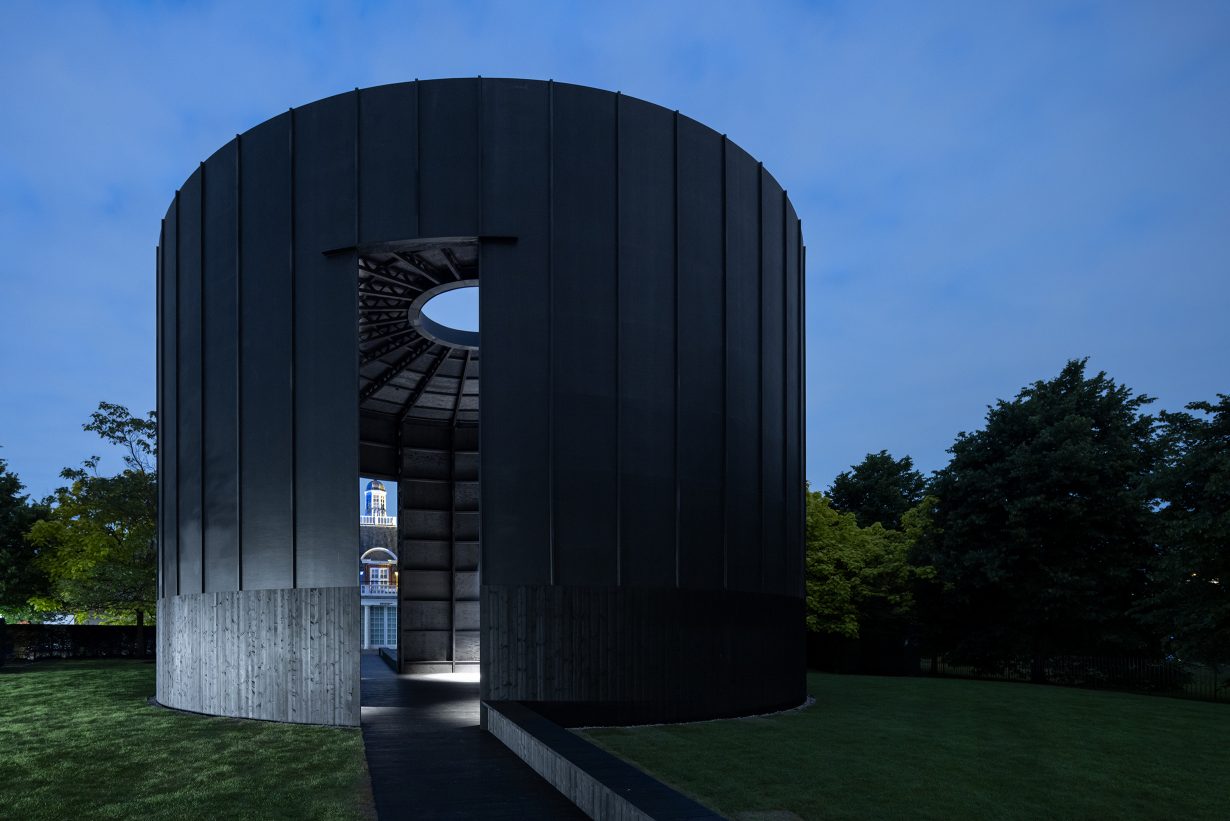

Last week in London, Gates presented his Serpentine Pavilion commission, a 10.7-metre-tall, 16-metre-wide cylindrical edifice erected with the support of the ubiquitous architectural firm Adjaye Associates. Made of blackened timber and supported by visible steel trusses, Black Chapel’s conical roof opens to sky, sunstream and drizzle by way of an oculus, so that the roof offers shelter and exposure, a point of focus for those seated on any of the wraparound benches that line the wall. Furthest from the doorways hang seven of Gates’s tar paintings, here in homage to the artist’s late father, a professional roofer. Opposite the paintings is a walled-off cafe and bar. Outside, on the freshly laid, vivid lawn, sits a large, worn bell salvaged from the now demolished St Laurence church on Chicago’s South Side and transported here to summon audiences together for performances.

One reading of Black Chapel is as a vessel – in keeping with Gates’s practice as a potter and builder of structures that hope to support others. The ‘Chapel’ suggests reflection and contemplation in the style of a religious sanctuary but without the ecclesiastical trappings. Much of Black Chapel’s possibility will likely emerge as the public and those slated to perform as part of Serpentine’s Park Nights programme move through it. These include Black British artists Corinne Bailey Rae and Moses Boyd. But Black Chapel also lives within the context of the Serpentine, and it bears saying that despite its size, and despite its blackness in the verdant park, Black Chapel is unobtrusive, nestled within Serpentine’s black fence, and with some of its sight lines oriented towards the Serpentine South Gallery – one of its sharpest views is on the building’s iconic weather vane, perhaps a quaint remnant from when Serpentine South was a tea house.

The work, too, feels oriented more towards the existing audience of the commission, which is a highlight in London’s architectural and artworld calendar. This is merely a function of a commissioning structure that invites an architect who has never built in the UK to design and realise a structure; the community that is invoked is highly specialised; more local interaction is not what it intends to support.

Black Chapel pays tribute to industrial and domestic structures: Gates’s named references include English bottle kilns, US beehive kilns, and Musgum adobe homes of Cameroon, structures that have aided humans in shaping the earth. It also resembles the defunct gasholders dotted around London that developers are increasingly converting into expensive apartments. This particular structural resonance speaks to a larger context: the Serpentine is situated in Kensington Gardens, formerly the private gardens of Kensington Palace, and one of London’s royal parks. The park – which straddles the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea and the City of Westminster – is fastidiously maintained and displays a version of public space that conspicuously depends on who is excluded.

At least from the vantage point of the Serpentine Gallery, the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea might at first appear enriched, not ravaged by the government’s austerity policies. Elsewhere in the borough, however, stands a fire-blackened building; Kensington and Chelsea is currently at the centre of a public inquiry into the malignant negligence that culminated in the 2017 Grenfell Tower Fire – and that continues to fail its survivors. Black Chapel opened to the public within days of the Fire’s fifth anniversary. Inside, sleek lengths of blackened timber stretch with barely a visible join; even the tar paintings illuminating the interior seem an elegant design flourish rather than integral to the structure. Gates said at the press view that Black Chapel is “about Blackness,” which he names as “the ability to remain open, to remain optimistic, to remain active in one’s cultural and spiritual life even though the truth of subjugation is all the fuck around you.” In this moment, he seemed to gesture beyond the Serpentine in ways that the work does not quite manage to, despite its global references. In this dense context, of carefully obscured poverty, scandal, and manicured colonial beauty, it is unclear what Gates’s Black Chapel itself has to say.