If the museum is a place both of remembering and repression, its relationship to historical facts is always unstable. How can art make space for those who history left behind?

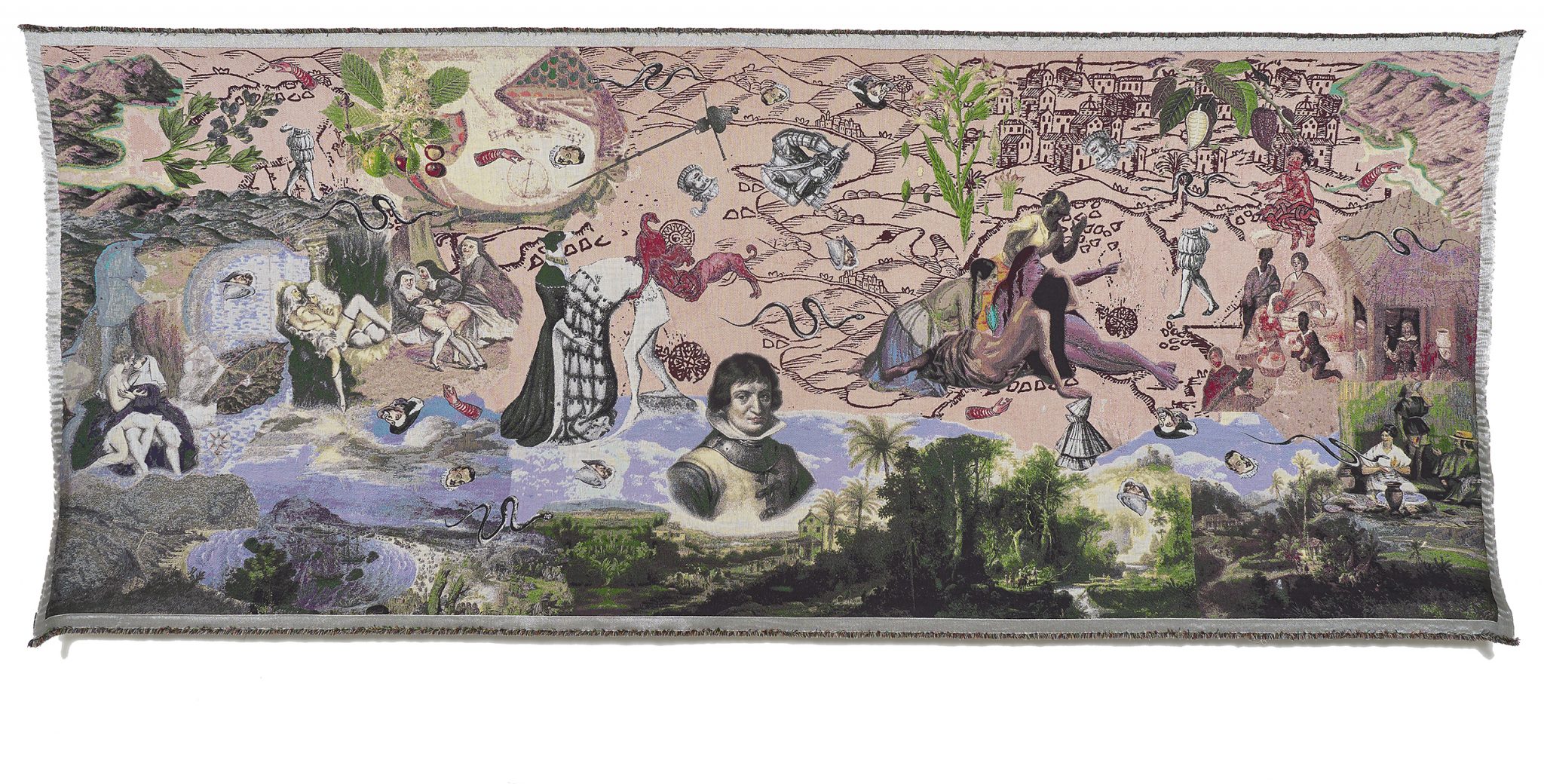

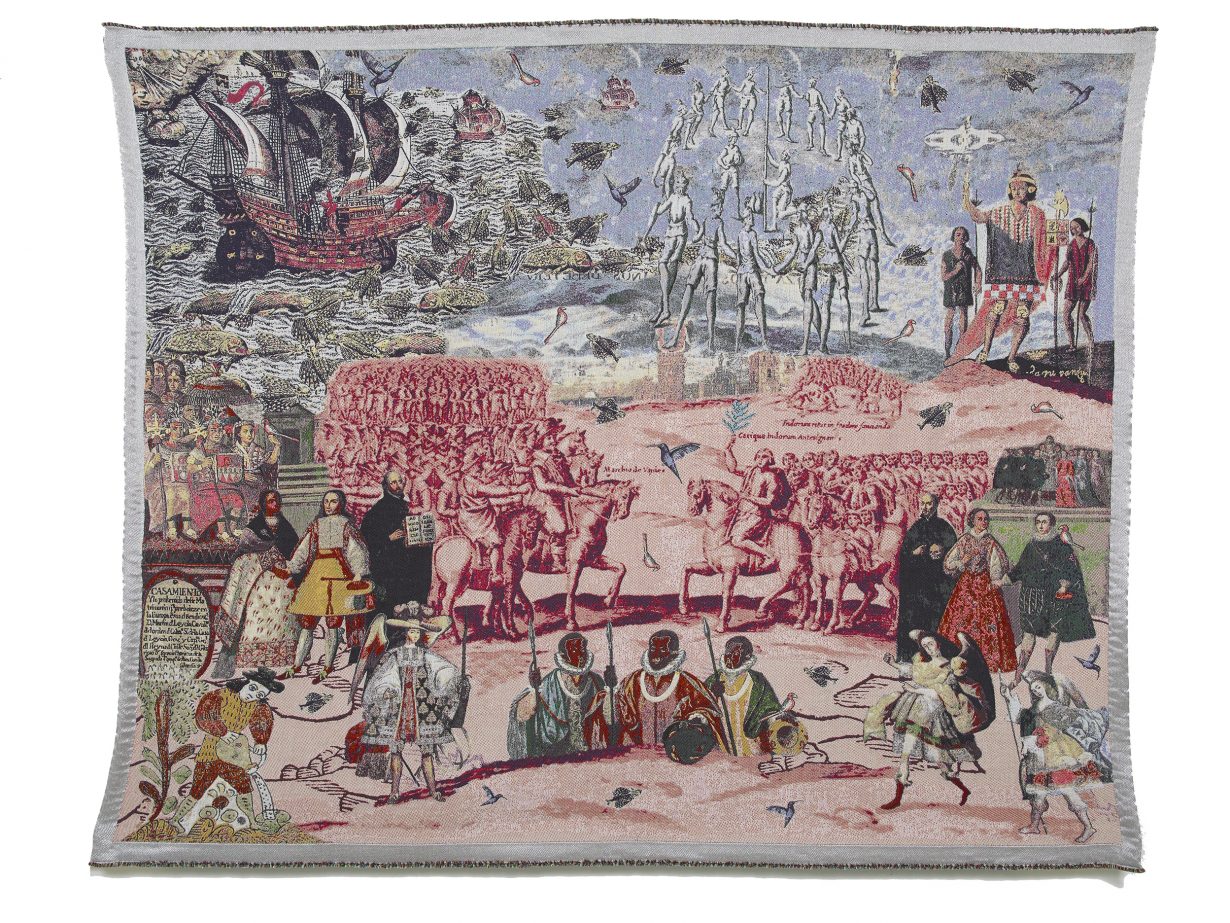

Mercedes Azpilicueta’s jacquard tapestries trace the conquest of the Americas across the sixteenth century: a time of violence, uncertainty and change. The Argentinean artist often focuses on the lives of individuals, such as the legend of Lucía Miranda, a Spanish woman allegedly captured by Indigenous people, and the life of Catalina de Erauso, an ambiguous folk hero, also known as the Lieutenant Nun. The Lieutenant-Nun Is Passing: An Autobiography of Katalina, Antonio, Alonso, and More (2021) is a four-metre-long tapestry exhibited in a sculptural dressing frame, which narrates Erauso’s life in pastel-coloured wool: horny nuns lift up their skirts to fuck each other, dogs are dressed in jewels and gowns, snakes slither, cocoa beans fly and indigo flowers drift by. In 1600, at the age of fifteen, Erauso escaped from a convent in San Sebastián, in northern Spain, and hid in a chestnut grove. There she took off her veil, cut her hair and transformed her bodice into breeches. Later, Erauso boarded a ship disguised as a boy and travelled to the Americas, taking on new identities, including Antonio de Erasco and Alonso Díaz. Erauso would spend 19 years living in the ‘New World’, his life eventually recorded in an autobiographical memoir published centuries after it was written.

Erauso is a dazzling, multifarious figure; a rebel who escaped the confines of a convent and lived as a man. The swashbuckling memoir (itself a slippery source that blends biography with fiction) relays Erauso’s escapades, as he became a famous conquistador – a bloodthirsty, ruthless soldier of the Spanish empire, who relished in killing Indigenous Mapuche Chileans. Indeed, Erauso’s exploits as Antonio were so legendary that, on return to Spain, he obtained the Pope’s blessing to pursue life as a man – the ultimate validation. This immersion into colonial patriarchy means that Erauso is perhaps not quite the hero that queer artists and historians tend to desire in subversive historical figures. Rather, Erauso qualifies as a ‘bad gay’: a humorous moniker devised by podcasters Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller to describe ‘complicated queer people in history’ who are often left out of contemporary narratives today.

Azpilicueta is one of many South American artists, including Gê Viana and Laíza Ferreira, employing engravings, maps and other archival imagery as source materials to consider the way history is constructed in the present. ‘But how do historians discover… things about anyone in the past?’ asks the historian Natalie Zemon Davis in The Return of Martin Guerre, her 1982 book on the lives of sixteenth-century peasants. ‘We look at letters and diaries, autobiographies, memoirs’, she explains, before highlighting a central problem: these documents are penned by a literate minority. Those unable to write ‘have left us few documents of self-revelation’, Davis continues, pointing out that the peasants she attends to have bequeathed little in their own words.

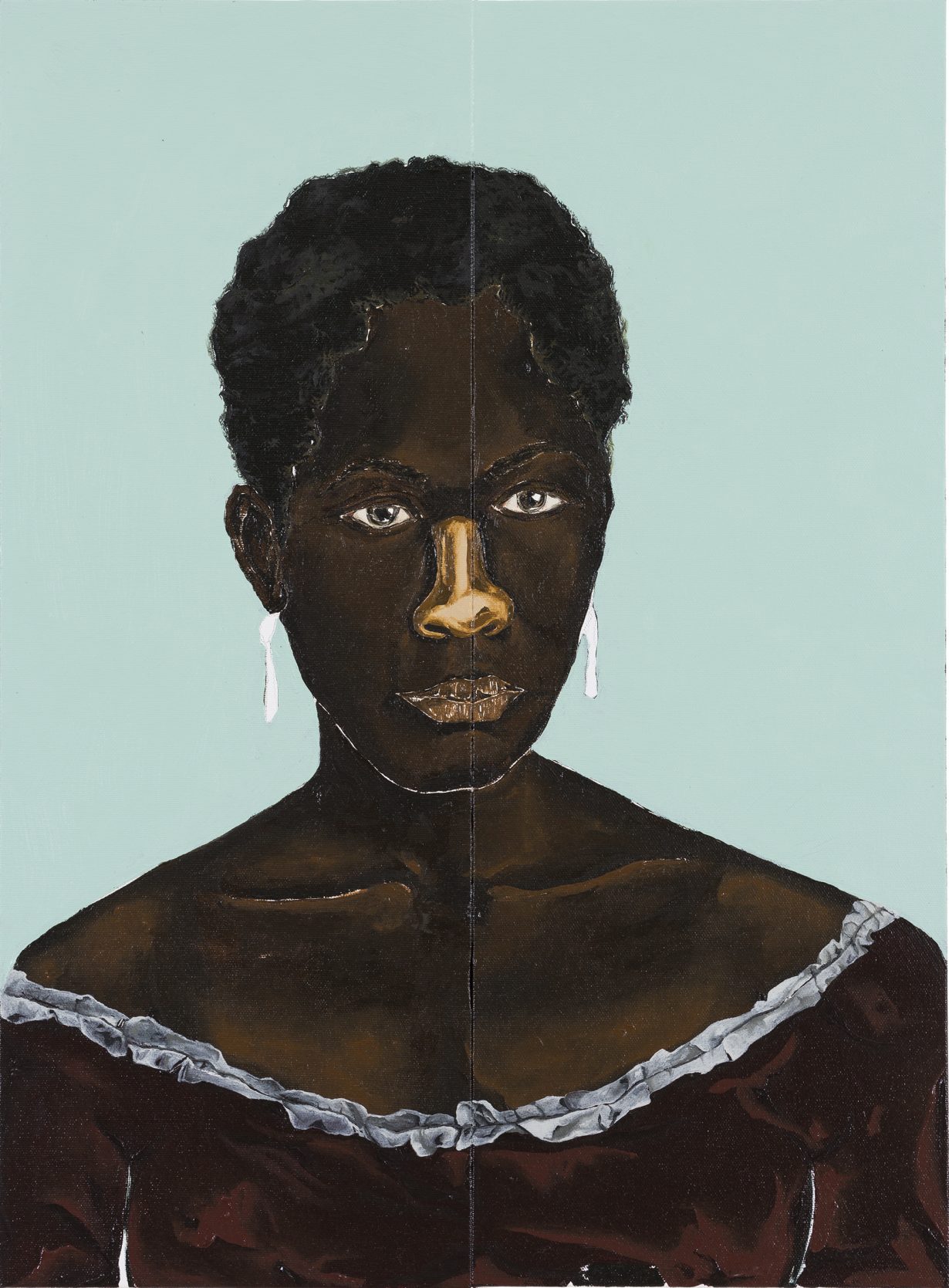

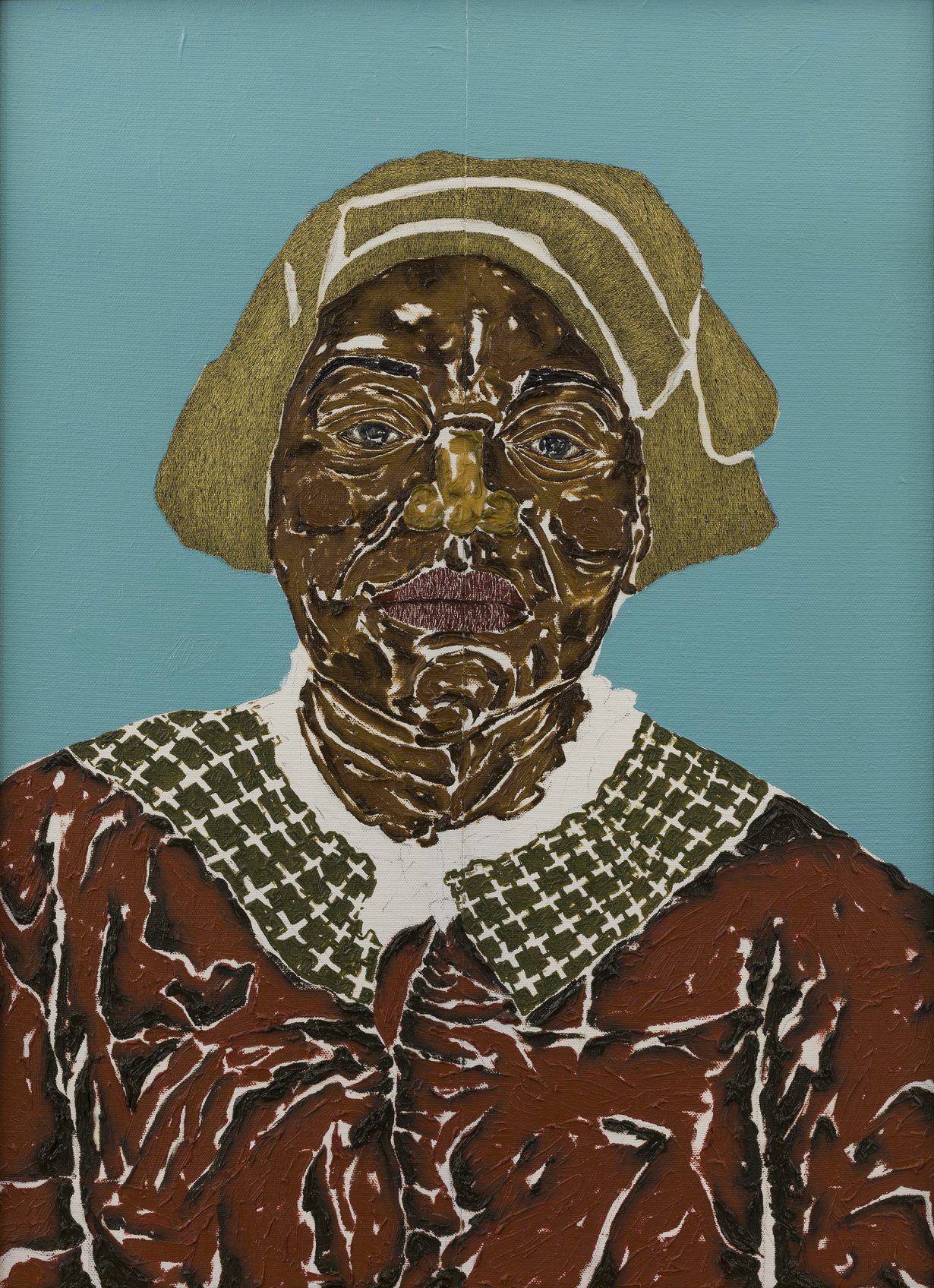

This historical bind can pose a conundrum for historians, but also opens the door for other creative methods. The US scholar Saidiya Hartman has developed an especially inventive approach. In her writing, she considers the role that our imagination can play when it comes to narrating the lives of Black women living in the United States after emancipation; women who have rarely left behind any such ‘documents of self-revelation’. Rather, Hartman discovers her subjects in a very different order of document: the trial transcript, the prison case file and the vice investigator’s report, in which Black women are considered a problem that requires discipline and correction. In response to the violence that marks these sources, Hartman crafts what she describes as ‘counternarratives’, at times using fiction to give her subjects an interior life. In an essay from 2008, she described this method as ‘critical fabulation’, initiating a genre of writing. ‘I have pressed at the limits of the case file and the document, speculated about what might have been, imagined the things whispered in dark bedrooms’, Hartman explains in her book Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments (2020). Her method has inspired artists, from the Brazilian painter Dalton Paula, who portrays Black Brazilians who have never been visually represented, to the Trinidad and Tobago sculptor Shannon Alonzo, who describes archive photographs as ‘portals’ through which she communes with anonymous women of the past.

These artists create a missing ancestry by recovering forgotten lives. Other artists have gleaned traces of queer lives in literary sources. Jamie Crewe’s videowork Adulteress (2017) is one such example. Its subject is a pornographic novel by the French writer Rachilde, titled Monsieur Vénus (1884). The novel tells the story of a masculine noblewoman who subverted her gender in the pursuit of sexual pleasure – and is, along with her lover, eventually punished. In the video, Crewe presents a chapter of the novel through subtitles, juxtaposing the text – an episode of sexual jealousy and suspicion – with a visual adaptation. Onscreen, the artist imagines a new scenario, in which the noblewoman’s lover escapes punishment to freely explore their gender; the resulting scene shows Crewe and their friends putting on makeup, laughing and chatting. The gap between text and image is thrilling, an irreverent interpretation that dramatises a deliberate misreading of the text, drawing out what is dormant or hidden; to adapt, after all, is to adjust to fit the present.

In his lush historical novel about the life of an eighteenth-century folk hero, Confessions of the Fox (2018), Jordy Rosenberg posits another, more extreme method of utilising history. The novel imagines a group of ‘radical’ librarians who break into libraries by night and alter historical manuscripts. ‘Late at night, during school holidays, a number of stacks nationwide had been infiltrated and – how to put this? – edited,’ the narrator reveals. These librarians ‘improve’ historical sources by ‘correcting’ ahistorical tendencies, such as the representation of seventeenth-century London as a uniformly white city, or the absence of queer lives. Confessions of the Fox poses as the lost manuscript of a legendary thief, modified for the present: the hero reimagined as a trans man, his lover Bess as a rebel of Indian descent.

Revising historical manuscripts is a fascinating and provocative proposition. On the one hand, editing the past can activate history’s gaps in representation, as Rosenberg’s novel powerfully demonstrates; but, at the same time, there’s a danger of overwriting documents that might serve to demonstrate the mechanisms of oppression, and the reasons why some stories prevail over others.

Azpilicueta does not seek to simplify Erauso’s life, to correct or improve the records left behind. Rather, she seems to revel in epistemological uncertainty, presenting a figure who is something more than a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ gay. Fabricated in stitches of violet yarn, The Lieutenant-Nun Is Passing presents a tropical landscape engulfed by a storm of images. The heads of white colonisers, Indigenous people and Black slaves fly across the land, at once decapitated and freed. The composition speaks to violence and displacement, as well as shifts in knowledge and scale. It can also be read as a dreamscape of Erauso’s life, inspired by magical realist traditions, giving form to a shapeshifting body, a life of many identities.

Another peril of overediting the past can be the blotting out of the unfamiliar and the strange. In their book, Before We Were Trans (2022), Kit Heyam considers the limits of current frames of interpretation when it comes to discovering queer lives. ‘[O]ur existing criteria for inclusion in “trans history”… privilege an incredibly narrow version of what it means to be trans,’ Heyam writes. This narrow criteria, created by a medical and legal paradigm, determines whose stories get circulated by the media, and whose are left to ‘languish in the dusty corners of second-hand bookshops’. Heyam’s book is a call to make space for messy and ambiguous histories, which can better reflect the variety of trans lives today.

The fictions of the present might be inescapable; Azpilicueta’s use of a jacquard loom – a machine that revolutionised the textile industry – points to the way that all history is in some sense manufactured. This insight, in turn, allows for possibility, because a tapestry of threads is ripe for unpicking and reweaving. There are two sides to Azpilicueta’s tapestries. The backs are a feverish mess of knots, while the same images are mirrored back in a wild cacophony of tangles. There is a baroque sense of excess, with its architecture of infinite folds, which allows room for convolution, accident and mess, and perhaps a widening of the window of insight – conditions that allow for revelation.

Izabella Scott is a writer based in London