Artists and unethical money have been implicitly linked for centuries. Whose role should it be to police it?

At first it looked legit. The unsolicited email wasn’t spam. Written by humans from a traceable organisation, its senders talked about their goal of facilitating global citizenship. They said they had an affinity for my work. They offered me $4,500 to make a digital artwork. I googled their website, so bland it might have been written by AI: positive buzzwords – ‘empower’, ‘collective’, ‘rights’ – pinged off each other with no final referent.

I searched again and found an interview with its founder. The ‘global citizenship’ they proposed would be subscription-only and ‘somewhat selective’, designed to mobilise a paying professional elite without facilitating equal freedom of movement for the cleaners, nannies or sans-papiers who constitute so much global mobility. Local social-security contributions would be opt-in. Like any international Bond villain, the organisation hoped soon to be ‘headquartered in a European castle’. This wasn’t a transparent commission. Was it artwashing?

Have you been asked to artwash? I put out a call on social media and what struck me was the variety of requests practitioners had experienced.

Artwashing isn’t a bug; it’s a feature of art, and it has a history: since before the Medicis, art has been commissioned to make power look good. The term was popularised around 2016 in response to art’s involvement in the gentrification of the Boyle Heights district of Los Angeles. Making work with communities is superficially feelgood, but art that makes an area look more desirable can feed into – and is often commissioned by those with a stake in profiting from – higher property values, eventually displacing the communities involved.

Artwashing is a thing for exactly the reasons art is difficult to value and often badly paid: art has a reputation for operating beyond capital, allied to community, personal expression, social justice and fun. “The flip side” of artwashing, as Irish artist Suzanne Walsh told me, “is artists being asked to ‘give back to the community’, donate works, fundraisers, for free. But of course,” they added, “we do it because we want to, too.”

This confusion makes the fallout from artwashing not only financially but emotionally exhausting. What look like publicly funded commissions sometimes hide public-private-third sector ‘partnerships’ whose aims are more questionable. The creative workers who are at the sharp end of researching funders, and who have to take these ethical decisions in the absence of structured professional guidance or support, experience psychological as well as financial effects, ending up feeling compromised and finding it difficult to call the funders out. A writer who asked to remain anon still feels shame over nearly accepting a tainted project, and told me that living in the US “affected my experience of the project in ways that are very hard to articulate – the forcefield of manufactured ignorance in the US requires incredible will to expose oneself to truth”.

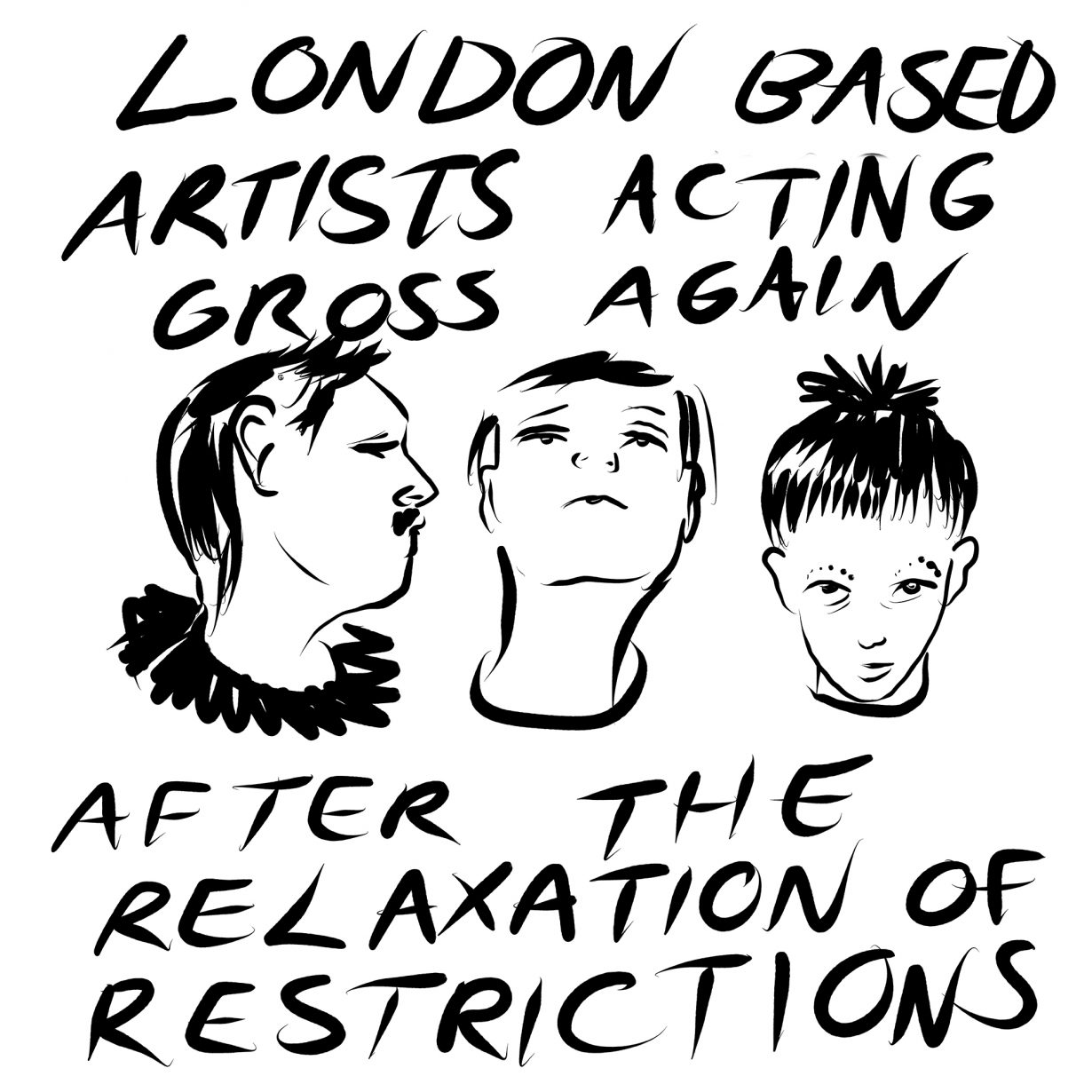

A freelancer working from gig to gig, I’m only too aware that artwashing is a form of censorship that silences the creative voices of artists living precariously. State arts defunding, especially in the UK and US, means that increasingly it’s the work of financially secure artists, or of those willing to accept a gift horse without taking it for a dental checkup, that gets made, distributed and promoted.

The good news is many artists, and some funding bodies, are rejecting this paradigm. One approach is initiatives that, instead of offering competitive one-off grants, address the problems created by such funding structures. For example Ireland’s state-funded Basic Income for the Arts scheme launched in 2022, which, if extended beyond the three-year pilot, will provide creative practitioners with an income of around €17,000 a year. Another is solidarity-based practitioner-driven activist movements like the UK’s Fossil Free Books, which last year persuaded Edinburgh Book Festival to divest from investment company Baillie Gifford.

Art is not an alternative to capitalism: it’s embedded in it, especially in its capacity to seem to offer an alternative. Artists’ positions as creative and financial sole traders – literal freelancers whose liquid labour can be made to serve a variety of causes – means that responding effectively to the problem of artwashing involves a reevaluation not only of funding structures, but of what ‘being an artist’ is.

Joanna Walsh’s Amateurs!: How We Built Internet Culture and Why it Matters (Verso) will be published in September

From the September 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.