In a year dominated by big-name filmmakers making their return, the film festival’s troubled history and questionable ethics were once again laid bare

Thierry Frémaux, délégué général du Festival de Cannes, agent of chaos. His personal triumphs at the helm of this year’s edition include (but are not limited to): selecting French director Maïwenn’s period piece Jeanne du Barry to open the proceedings (thereby orchestrating a rapturous homecoming for its star, Johnny Depp); criticising the press who opposed this as hypocrites; then, separately, starting a fight with a police officer on the Croisette. It was a fraught time across France, too; as labour unions planned demonstrations against pension reforms at a moment of high visibility for the Riviera town, the festival organisers announced a ban on protests in the surrounding areas. ‘Aside from the pension reform, we’re also denouncing the way women are treated in the film world, but they don’t want us to stain the glittery image and standards of the Cannes Film Festival,’ Celine Petit, a union official, told Variety.

The festival’s troubled history and questionable ethics were once again laid bare. Cannes was once the business playground of Harvey Weinstein and the site of many of his abuses, and has played host to the likes of Roman Polanski, Woody Allen and Abdellatif Kechiche long after sexual and behavioural misconduct allegations were raised against all three. Women, meanwhile, have only in recent years been allowed to forgo high heels on the red carpet. And yet, the crowds still come for the movies. Maybe we are hypocrites, maybe we were just doing our jobs — perhaps it’s a little bit of both. Cannes is certainly still the key target for filmmakers, and especially this year for those eager to present their return to the craft after time away. The directorial comeback ruled the main competition: Jonathan Glazer and Catherine Breillat came to the festival with their first films in ten years; Trần Anh Hùng with his first in seven; and Nuri Bilge Ceylan, Alice Rohrwacher and Wang Bing each with their first in five. Out of competition, unfairly so, was Spanish filmmaker Victor Erice whose Close Your Eyes was his first film since 1992.

These all represent something of a safe bet: trusted auteurs making highly anticipated new work likely to reiterate their credentials. Yet this wave of well-known names, along with ticketing nightmares and the fact that many of these directors produced films over three hours long, meant that the time for new discoveries was limited. In the sidebar strands of ‘Un Certain Regard’, ‘Quinzaine des Cinéastes’, and ‘Semaine de la Critique’, fewer newcomer films garnered universal buzz – and certainly nothing to the extent of last year’s British hit Aftersun. Still, Senegalese filmmaker Ramata-Toulaye Sy’s debut Banel & Adama impressed and Argentinian Rodrigo Moreno’s transcendent, quasi-heist film The Delinquents was an ‘Un Certain Regard’ highlight.

Elsewhere, a guy called Martin Scorsese premiered Killers of the Flower Moon, a densely plotted and tightly structured account of the real-life murders of members of the Osage Nation in the 1920s, as told in David Grann’s homonymous 2017 book. It works in a mode of sheer volume, of overwhelming storytelling; at 206 minutes long, it spares no details in its account of the killings and the traumatic love story between Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio) — the mercenary, spineless nephew of Robert De Niro’s irredeemable businessman William Hale — and Mollie (a majestic Lily Gladstone), an Osage woman set to inherit a wealth of oil money headrights. It’s a story that demands its duration to understand the insipid greed and total manipulation of those involved in the Osage murders – and the wider persecution of Indigenous people throughout America’s history. But its duration works equally as a formal device to interrogate, and negate, sensationalism in the artistic retelling of true events.

The question of how history can be told through film is at the centre of Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest, which, through an adventurous and experimental cinematic grammar, imagines the life of Auschwitz commander Rudolf Höss (Christian Friedel) and his family in their home situated on the other side of the camp’s wall. Glazer’s signature eeriness, his deft handling of lurking horror, is maturely handled in this loose adaptation of Martin Amis’s novel. It’s an exemplar of the power of structuring absence, limiting what we see of the camp to foster even greater terror. Höss’s wife Hedwig (Sandra Huller) tends to her bucolic garden and their children host pool parties in the sun. But smoke billows from a tower in the distance; a scream is heard in the night; a gardener comes to spread ashes in the earth to enrich the soil. It’s a film that undulates with a kind of sickness, reinforced by visceral sound design and an anemic palatte for much of the runtime. At times, the frame is abruptly and feverishly taken over by solid block colour, jolting us into a moment of terrifying pause. Glazer’s formal approach is so carefully considered and strict, and these interruptions of sound and image hint at the way the truth of the circumstances begins to chip away at the steely, unconscionable blindness of the film’s milieu. This inventiveness makes The Zone of Interest a valuable piece of Holocaust cinema, and a skillful work that expands the potential of the medium as a whole.

Both Todd Haynes and Catherine Breillat returned to the main competition with compelling takes on transgressive age-gap romances. Haynes’s May December (an idiom referring to relationships in which one person is significantly older than the other) was a perfect showcase of the director’s skill for camp melodrama. By turns bitterly funny, sincere and absurd, the film follows Gracie (Julianne Moore) and Joe (Charles Melton) whose relationship began when the latter was only 13 years old. Gracie’s prison sentence and the tabloid hysteria weren’t enough to separate them and 20 years later, actress Elizabeth (Natalie Portman) shows up to research Gracie ahead of a film adaptation of their story. Haynes is clearly fascinated by methods of fabrication and performance in daily life — how people embody archetypes (like the housewife, a recurring cipher in his work) to externalise a desired persona, or a longed-for happiness.

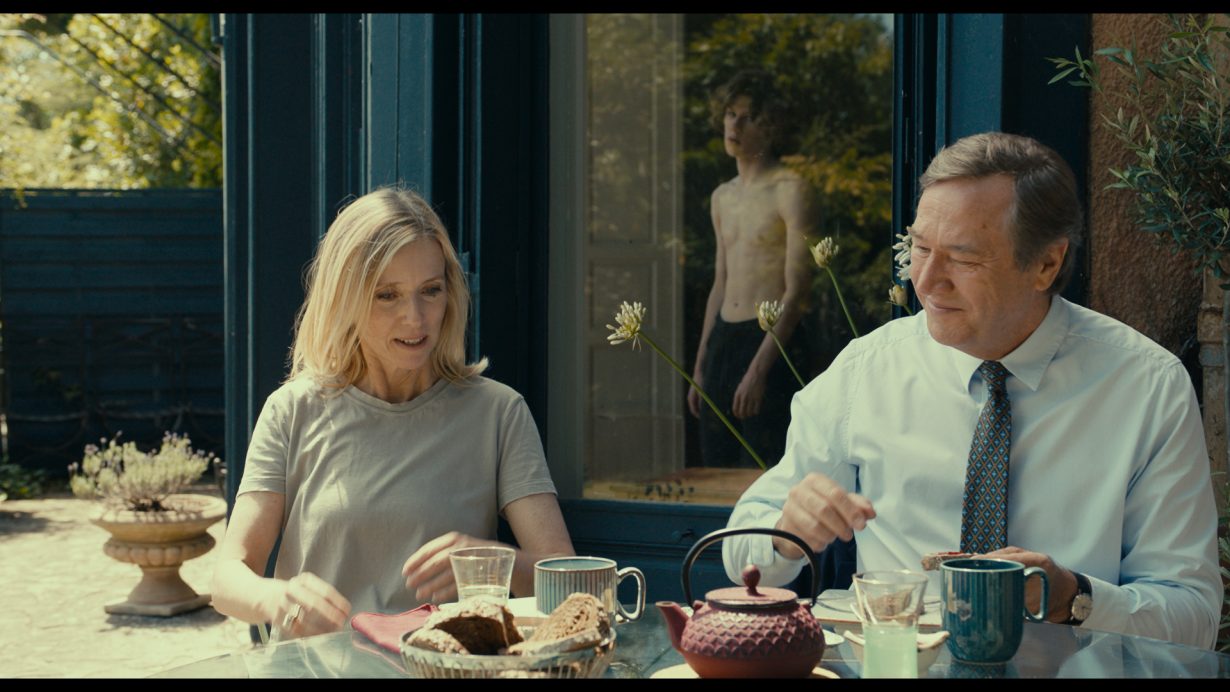

Breillat finds more romance in her provocative Last Summer, about a lawyer who starts a sexual relationship with her just-about-legal stepson. Breillat’s career-spanning interest in the illicit, erotic, often honest desires of women continues here but is tamed slightly; the broad subject of the film itself is controversial, of course, but her images and characterisations are not explicit in the way those familiar with her previous Romance (1999) or Anatomy of Hell (2004) might expect. Haynes and Breillat toy with these thorny, uncomfortable narratives in different tones. Both, however, fixate on desire and the role of denial in self-preservation.

A different kind of denial pervades both the festival and the broader film industry that descends on it each year. It’s too easy to enjoy the sunshine and oysters, to be grateful that Justine Triet won the Palme d’Or (just the third woman director to do so, for Anatomy of a Fall) and to overlook what happened at the start. Plus ça change. The discordance between the subject matter of some of the biggest films on display — explorations of class struggle, personal trauma, history’s atrocities — and the present political concerns of the festival, which slip by unnoticed, only grows more frustrating. Cannes still feels like the cinephile pinnacle, one that critics remain reluctant to give up on, but it’s a festival that seems happy to politically posture, associating its image with the work it programs rather than take any clear progressive stance. We can bask in the artistic merit of many of the films mentioned here – and that has always been the festival’s overriding power – but it’s becoming increasingly difficult to reckon with the towering brute that lays claim to it all.