A retrospective at Philadelphia Museum of Art celebrates Ramberg’s playful focus on the fetishistic rituals of femininity

About but not always of the body, Christina Ramberg’s paintings hold in tension its visceral realities and reductive representations, its strengths and vulnerabilities, its allure and repulsiveness. The earliest paintings in this retrospective are small square panels depicting fragmented body parts; mostly heads of hair seen from behind, as in the 16-part Hair (1968). Though some are slotted into tabletop mirror stands, there are no faces to be found here or elsewhere in Ramberg’s imagery. That her typically female subjects – often shown bound, cloaked or in compromising positions – do not look back at us implicates our gaze in the power dynamics of her pictures. Part of Ramberg’s self-described strategy of ‘withholding information’, the absence of faces also produces an objectifying anonymity that became literalised as her increasingly abstract figures merged with their adornments.

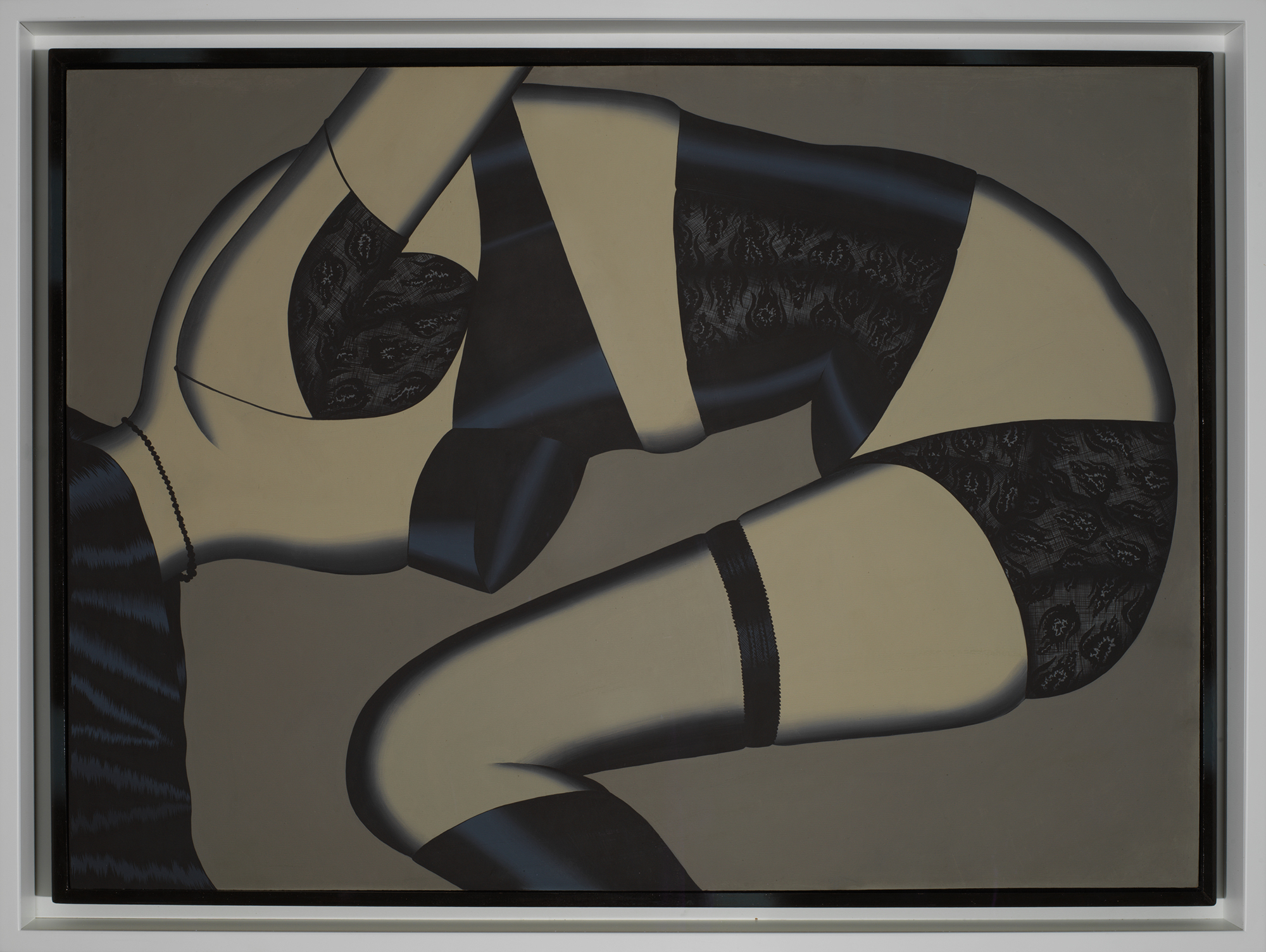

Ramberg studied at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where she worked among artists who became, like her, associated with Imagism, an informal movement advancing a graphic figuration that fused Pop and Surrealism. From the beginning she painted almost exclusively with acrylics on Masonite panels, meticulously sanding the surface to remove evidence of brushstrokes and achieve the airbrushed mattness of commercially printed material. The squeaky-clean fetishism of Ramberg’s process undercuts the sexual fetish- ism of her imagery, which she derived, in part, from comic books, lingerie advertisements and erotica. If, for example, there is any eroticism in Black Widow (1971), a painting of a woman undressing to reveal a lustrous corset, Ramberg undercuts it with her wan palette, mannequin-like rendering and a detached profile view. These early paintings of idealised women in constraining lingerie suggest Ramberg’s ambivalence towards such imagery. Seemingly uncertain whether they should appeal or critique, and probably wanting them to do both, she put the images in conflict with themselves.

The eight-panel acrylic painting Corset / Urns (1970) opens the artist’s extended consideration of the torso, as woven and braided hair morphs between vessel and body-shaping undergarment. Ramberg also conflated human midsections with armour, chairbacks and origami, a process she referred to, in the margins of a nearby drawing, as ‘a cross breeding’. Through the 1970s her figures become increasingly abstract, challenging and deforming the archetype of her earlier subjects. Hair develops a mind of its own: rogue locks snake and coil like tails, burrowing into and sprouting from unexpected places on the body. Sinewy bands of hair have fully replaced apparel in Wired (1974–75) and Broken (1975), wrapping the gangly arms and cinched waists of headless humanoids. Later in the decade, while Ramberg was raising her young son, the ‘bodies’ she envisions are hollow and fractured, like the disintegrating armature of Schizophrenic Discovery (1977), and then, as with Hearing (1981), heterogeneous assemblages of spare parts – containers or wombs nesting smaller figures within. Ramberg had effectively taken objectification to its end point: only a cursory human resemblance remained.

The exhibition closes with two lesser-known aspects of the artist’s practice. Made throughout the 1980s and exhibited as art during her lifetime, Ramberg’s quilts reinforce her interest in pattern and serial repetition. A final series of abstract black-and-white paintings from 1986 evoke the skeletal scaffolding of satellites and radio towers, both communication technologies; sketchy, diagrammatic canvases that have a searching, indeterminate quality more akin to Hilma af Klint’s mystical abstractions. If Ramberg’s later works seem like dramatic departures, it’s mostly because her development had previously been so linear. It’s as if the artist – in the period just before she was diagnosed with a debilitating neurodegenerative disease that would force her to stop making art – was finally relieved of the body’s burden.

Christina Ramberg: A Retrospective at Philadelphia Museum of Art, through 1 June

From the April 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.