All Day All Night at the Whitney offers a recalibration of our relationship with sound and language, and fights for those it excludes

At first blush, Christine Sun Kim’s fascination with language centres less on its poetics than on its conventions. Across the videos, site-specific murals and the myriad series of charcoal line drawings that make up her retrospective at the Whitney, Kim charts an erudite understanding of language-as-system – an interlocking set of symbols, signs and echoed meanings best made visible through the economical lines and blunt phrasing of her works on paper. Taken in concert, the totality of Kim’s work – and the overall effect of the exhibition – offers a recalibration of our relationship with sound and language.

Arranged loosely chronologically, the exhibition starts with Kim’s early experiments recasting sound as visuals: in pieces like Selby Circle and Selby Square (both 2011), she used vibration to splatter blue ink across wooden boards, effectively ‘mapping’ the noise, illustrating it as something to be witnessed as much as heard. Born deaf, Kim’s fascination with sound blossomed after recognising that despite not hearing, she moved through the world with a conscious deference to it. Cataloguing its impact visually, she grew fluent in its obvious effects on others. Situated in glass vitrines, the two ink-splattered, Jackson Pollock-like boards are surrounded by a series of drawings riffing on the conventions of musical notation, and specifically the sign ‘p’, which is used to signal softening in a score. Kim takes the concept and expands it into patterns: grids and triangles formed by the symbol ‘p’ are paired with musings about how one might illustrate and capture quietness, and further still, how silence can become idiomatic (as in ‘the silent treatment’), a saying that holds no meaning if the words are not spoken to begin with.

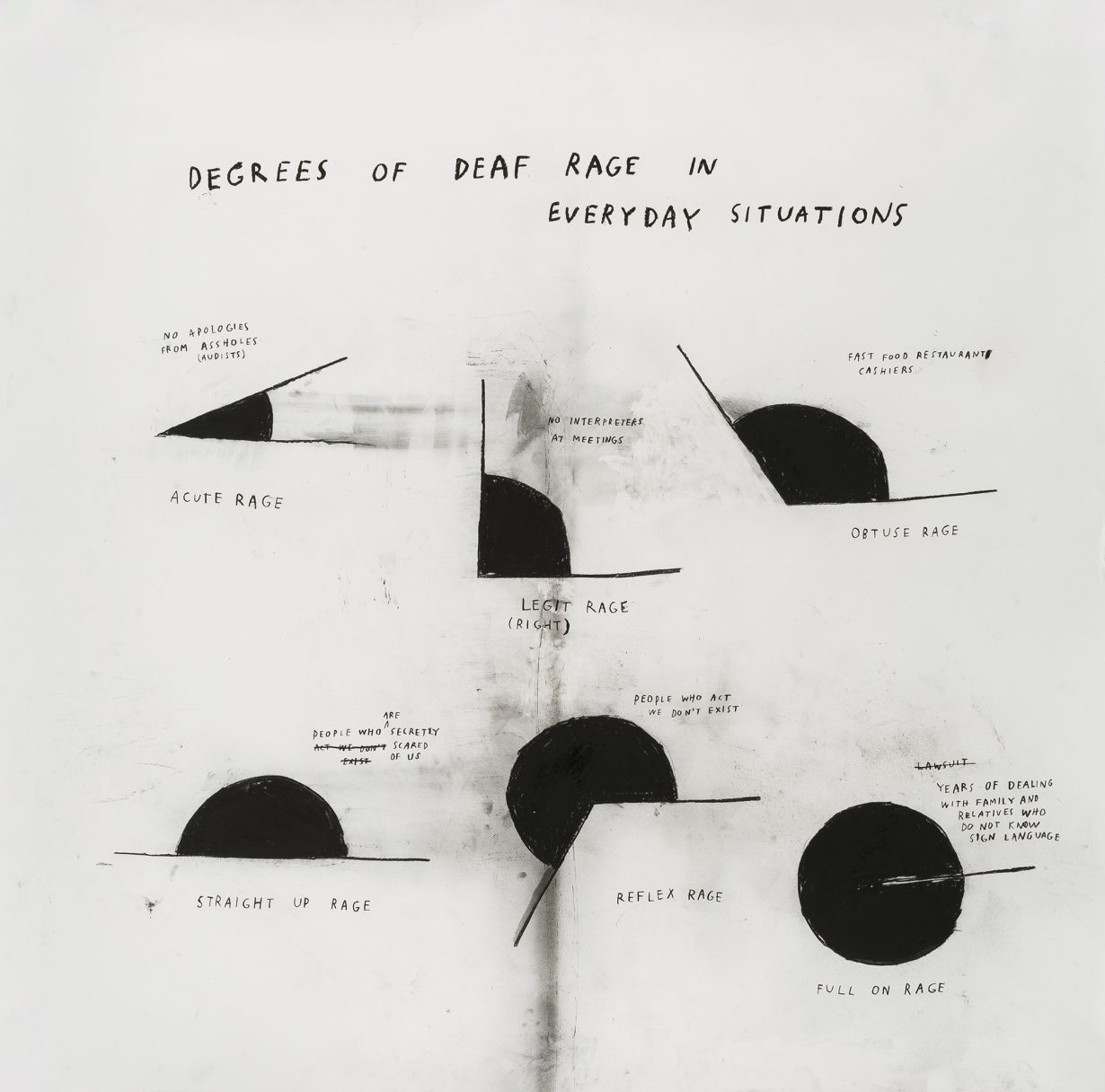

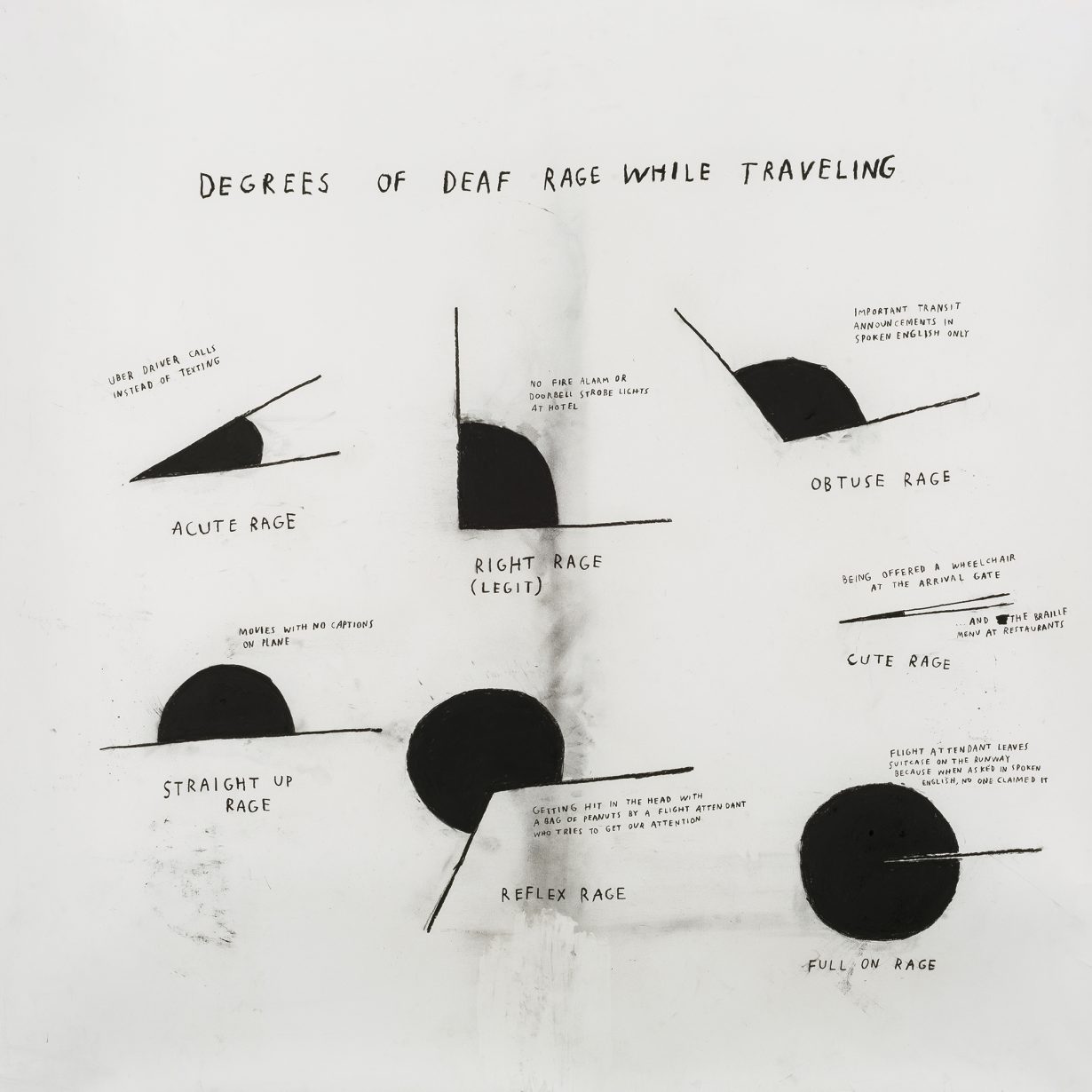

As Kim incorporates ever more text into her charcoal drawings, her fascination with sound yields to questions around language itself. Here, there is a clear and welcome activist edge to Kim’s practice. Determined that social currency find other, soundless vectors to travel across, Kim sketches out angles and pie charts, captioning each geometric sliver with a different feeling, diagramming her experiences. Evocative of infographics, the series Degrees of My Deaf Rage (2018) details her repeated frustrations with the assumed neutrality of spoken language, charting her anger with everything from the Guggenheim accessibility manager (acute rage, illustrated with a charcoal-smudged corresponding angle) to ‘curators who think it’s fair to split my salary fee with interpreters’, which sparks a reflex rage, the angle of which is coloured in a solid, inky black.

Given Kim’s attention to language’s role in constructing our understanding of the world, it’s no surprise that the theme of translation surfaces continually across her work. From her early performance piece Face Opera II (2013), captured on video and on view in the first gallery, to her later series of drawings ‘Terp Voices’ (2015), Kim often references the pains of working with an interpreter, and the ultimate resignation of having her language – and by extension, herself – mediated through others. Her series ‘English vs Deaf English’ offers an explicit visualisation of just how clumsy one-to-one translations between the signed and the spoken can be: the pages are divided into two columns with phrases scratched out in all-caps showing how ‘ate’, becomes ‘eat finish’, or ‘can’t see a thing’, gets signed as ‘see zero’. The drawings remind viewers of language’s structural edge: that the conventions of American Sign Language (ASL), its very syntax and grammar, avail it of a multitude of meaning that cannot be reduced to fit spoken words.

Kim’s work proposes we might instead expand on the authority given to languages beyond spoken English; that in translating an idea that operates spatially into sound and vice versa, there is an opportunity to broaden the bounds of meaning itself. There is an enormity of expression available exclusively in ASL, a language in which time is marked by distance, grammar is marked by motion and concepts are distilled not into letters but physical space. So long as both languages are given equal respect, the rub of mistranslation, propelled by the necessity of communication, offers a chance to pressure-test any given thought. And it is here that Kim’s practice starts to generate its own poetry.

All Day All Night at Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, through 6 July

From the April 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.