Both artists, posthumously united in a group show at ICA Milano, sought to identify and escape the burden of culturally instituted gender roles

There are so many affinities between the creative universes of Cinzia Ruggeri and Birgit Jürgenssen that, looking at this juxtaposition of their practices by artist Maurizio Cattelan and curator Marta Papini, it’s surprising that they apparently never met. Born seven years apart – artist/designer Ruggeri (1942–2019) in Milan, artist/educator/curator Jürgenssen (1949–2003) in Vienna – they moved freely between disciplines, making themselves – in the title’s poetic argot – ‘bridges’. Ruggeri’s eclectic Fluxus-influenced oeuvre merged fashion, design, art, music, architecture and performance; Jürgenssen moved between photography, drawing, painting, sculpture and clothing, infusing everything with an ironic tone harkening back to Dadaism and Surrealism (Meret Oppenheim seems to have been a signal influence). As the exhibition text points out, both artists used their diverse languages to investigate, among other things, the female body, its transformation, clothing as an expression of identity and ways to escape the burden of culturally instituted gender roles.

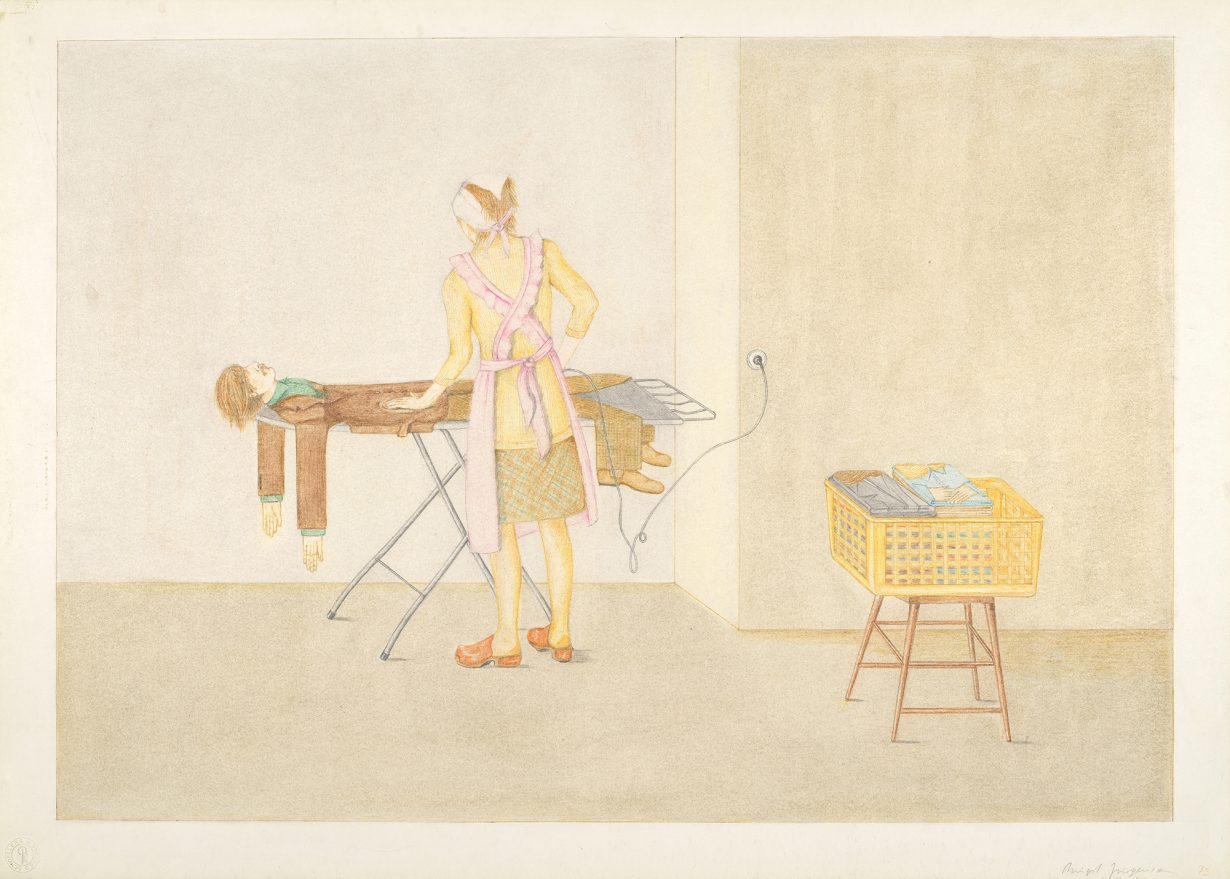

Specifically, both artists fetishised inanimate objects and dealt wittily with ornaments and accessories intended as extensions of the body, particularly shoes and gloves. In Jürgenssen’s Bed Shoes (1974), Nice Bird of Prey Shoe (1974–75) and Porcelain Shoe (1976), footwear turns respectively into a double bed, a bird, a foot-shaped porcelain vase. High heels are elsewhere transformed into metaphors for oppression: Ruggeri’s Shoe Stairs (1976) is a pair of heels installed on the wall by a door, as if about to climb ceilingward or make an exit. Her Oops, the Lost Glove (2004) is a glove conceived for the left hand only. Within the exhibition’s framework, this reinterpretation of accessories is also associated with a critical and satirical reading of the role and labour of women in the domestic and social spheres during the 1970s–80s: see, notably, Jürgenssen’s drawing of a woman intently ironing the silhouette of a man in Housewives’ Work (1973).

Favouring humour and acuity over a chronological or philological approach, the exhibition emphasises formal and visual connections between sculptures, photographs and drawings, which mingle here like characters. Recurring themes such as staircases, shadows and doubles serve as handholds for navigating the show, and works can operate as background or foreground: hanging against Jürgenssen’s wallpaper Aesculapian Snake (1978), an enlarged drawing in which the hair of a naked woman descending a set of spiralling stairs becomes a snake’s long tail, is Ruggeri’s green, staircase-inspired Dress (1985). Shadows are placed in visual dialogue between Ruggeri’s Colombra (1990), a black textile sofa sculpture representing a figure simulating a dove with hands (as in shadow puppetry), and Jürgenssen’s Untitled (finger cots) (1988), colour photographs in which the artist presents alienlike shadows of her hands, the tip of each finger warped by what appears to be an air bubble blown into the medical wear. Doubling, meanwhile, is explored in a room featuring iconic works such as Ruggeri’s Italy Boots (1986), a pair of boots, each boot the shape of the Italian peninsula, climbing a small step ladder, and Jürgenssen’s I’ll Play the Match with Myself (1973), a self-portrait in pencil, in which the artist plays tennis against herself, head transformed into a racquet.

Lonely Are All Bridges might be valuable enough for its innovative curatorial intermingling. More than that, though, it showcases twin practices whose legacy and example feel relevant today: Ruggeri and Jürgenssen, it’s clear, were masters of hybrid fields of research, bold and devoted experimenters towards fertile contaminations, and operated without fear of social and cultural stigmas.

Lonely Are All Bridges at ICA Milano, through 15 March

From the March 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.