The Balinese artist’s paintings subvert old sources to tell new tales

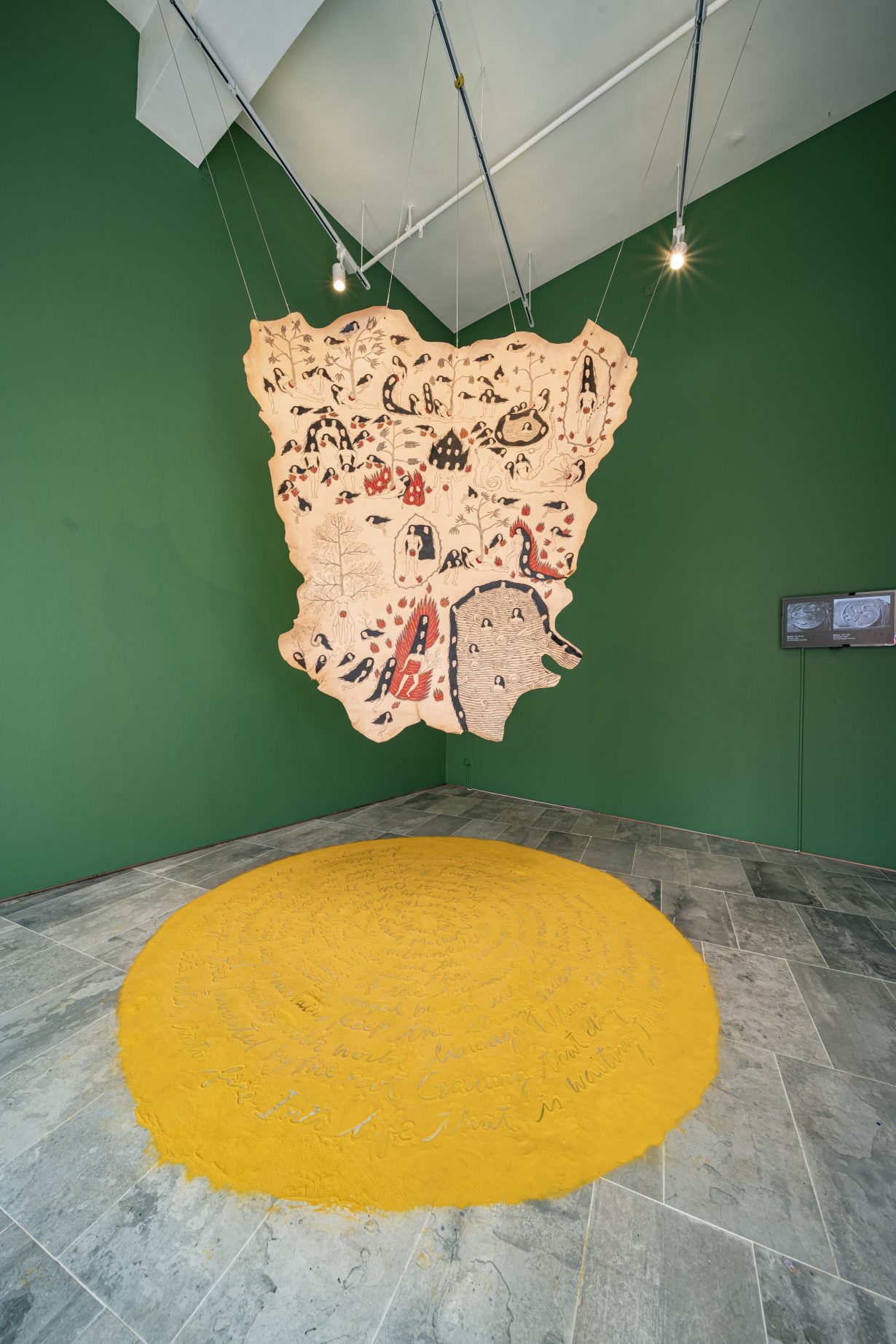

Allegory of Archipelago (2023), currently showing at the Bienal de São Paulo, is a teeming, churning phantasmagoria of heaven and hell and everything in between. Created by Balinese artist Citra Sasmita, the work takes the form of a largescale installation comprising several suspended painted scrolls. Central among these is a nine-metre-long canvas floating horizontally, depicting a tripartite cosmology starting with a harmonious Edenic realm of supersize tree- and snake-women, then descending to an earthly zone of war, before ending in a fiery underworld of heads on stakes and figures in boiling cauldrons.

This mythological view of the Indonesian archipelago is combined with a pointed critique of the country’s violent colonial legacy. In front of the scroll, on the ground, is a golden figure of a kneeling Caucasian man holding a money bag. The statue is a replica of an actual figure that was placed in front of the gate at the royal palace in Klungkung, the last Balinese-kingdom holdout against Dutch invaders during the early twentieth century. After razing the palace and destroying its original Hindu statues at the gate in 1908, the Dutch replaced the them with figures of white men to be worshipped by the local population. In the artwork, a rope runs from the bottom of the painted scroll and winds around the figure’s neck in a noose. The gold-plated squatting idol – symbolic not just of colonial greed and conquest, but of cultural brainwashing and perhaps, as recent history has demonstrated, even the overarching power of Western neoliberalism – is gnomish, vulgar, powerful.

For the past decade or so, Sasmita has been revisiting ancient mythologies and reviving traditional artistic techniques to critique patriarchal and colonial legacies in her native country. In her paintings, she replaces origin stories from the Indonesian archipelago with her own visions of a female-centred cosmology, by drawing on various models of strong feminist archetypes from Hinduism (which started to arrive in the archipelago during the first century and the contemporary practice of which, in Indonesia, centres around Bali) and from Indonesian history, and by simply inventing her own goddesses and their magical abilities. In authoring her own mythos of the feminine, she revisits figures of anticolonial resistance, folding their stories into her teeming canvases.

Sasmita’s work is also subversive because of the way she has creatively appropriated Balinese Kamasan painting, a highly detailed traditional artform used to depict myths and romances from Hindu and indigenous sources. Its origins are unclear, but scholars believe that Kamasan painting was influenced by court art from the East Javanese Majapahit Empire. In Bali, this style of painting blossomed from the sixteenth to the twentieth centuries, with the village of Kamasan, which is located between the east coast and the mountain ranges of Gunung Agung, becoming the centre of production.

Kamasan paintings, whether as temple frescoes or on canvas, are typically executed by male artisans. They are painted in a flat, busy composition that is crowded with figures such as deities, princes and noblemen. Empty space is adorned with natural decorative motifs such as flowers and trees. The works depict scenes from Hindu epics such as the Mahabharata or the Ramayana, as well as Javanese classics such as the Panji tales, centring on the adventures and exploits of the titular Javanese prince on a quest to find a beloved princess. Women occupy a peripheral role in these masculine discourses, typically as victims, as ornamental, sexual objects or as villains, like witches.

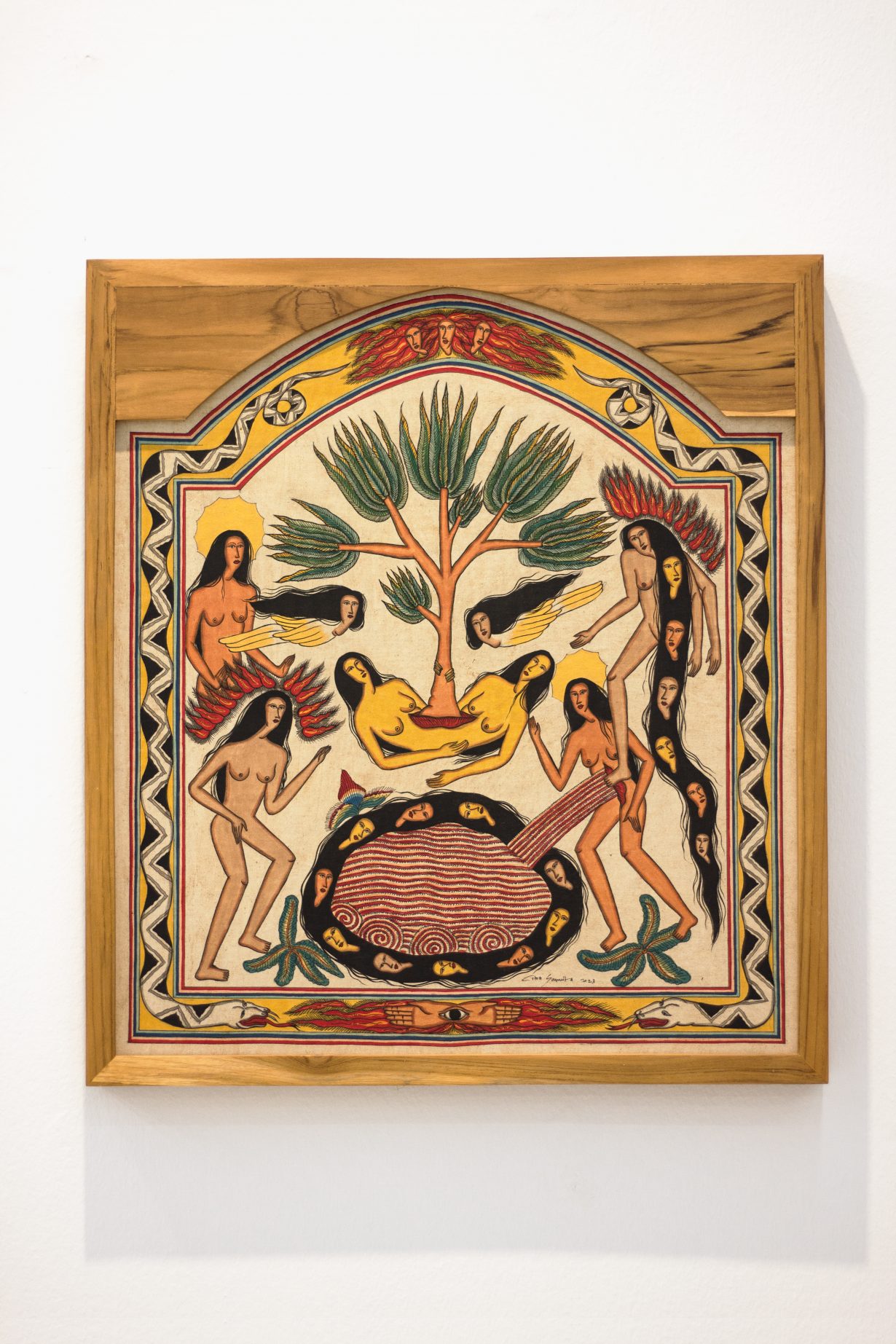

From 2019, as part of her ongoing Timur Merah (The East is Red) series, Sasmita flipped the script on these traditional tales. She retains elements of original Kamasan iconography, such as the flat figuration, crowded composition and recurring decorative motifs, and she uses traditional Kamasan canvas, which has a distinctive pale-ochre colour (it is usually prepared by artisans in a painstaking process that involves dipping the canvas into rice porridge, drying it in the sun and scraping the surface repeatedly with a shell to smooth it out).

Where she parts ways with tradition is in her content. In Theatre of The Doom (2023), a representation of the Day of Judgment, the line dividing sinners from saints, and suffering from ecstasy, is unclear. The work is split diagonally into four main zones; each is crowded with nude female figures in states of violent, radical change. Some of their heads and bodies are combusting. Others have trees bursting out of their torsos, necks and legs. Some have blood – enough blood to fill a pond – shooting out of a gash in their bellies. Severed heads are everywhere: some are skewered, others are stacked up like totem poles. Others still are split open to reveal heads within heads, like Russian dolls.

Yet these women seem at peace. Their faces have blithe, serene expressions, even as their bodies undergo ferocious transformations. In a sense, it’s a Day of Judgment without a sense of judgment, in which categories of good and bad, animal and human, become eroded or irrelevant. The women depicted here create and destroy with impunity and freedom.

Hindus, especially the goddess worshippers, might call the energy that they are channelling Shakti, the primordial force that is responsible for the creation, maintenance and destruction of the universe – and which is associated with the feminine divine. But Sasmita’s iconography is eclectic and personal. Her work celebrates a universal, unending and revelatory cycle of change that flows through living beings, rending them and stitching them together again, in which bodies become continuous with other bodies and beings, in an eternal process of becoming and unbecoming.

A key inspiration, says Sasmita, is Dewa Agung Istri Kanya, a warrior-poet queen from the Klungkung kingdom who ruled Bali from 1814 to 1850 and led native troops to repel Dutch forces during the battle of Kusamba (1849). While she has appeared as a heroic leader in several works, the queen’s life and times were given the fullest treatment in the eight-panel installation Timur Merah Project VIII: Pilgrim, How You Journey (2022). In the first few scrolls, we see a Dutch warship rigged with batik sails, suggesting that it might come in peace. Inhumane Hindu rituals such as sati, the widow’s sacrifice on the husband’s funeral pyre, are shown side by side with colonial violence. When the queen makes her appearance, she is leading armed resistance against the Dutch. In other paintings, we see elaborate scenes of paradise and the underworld drawn from the Bhima Swarga, an episode from the Mahabharata in which a soul descends from heaven to hell, a story depicted in a famous painting on the ceiling of Kerta Gosa, a temple in Klungkung. (The Bhima Swarga was also evoked by the queen in her anti-Dutch propaganda.) The last painting depicts women on boats, referencing the slave trade during the Dutch occupation, which trafficked thousands of Balinese people yearly, including a great number of women, to other Dutch colonies.

Sasmita comes from a limited but impactful lineage of female artists who explore issues around female bodies and experience. She cites as a key influence the late Bali-born painter I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih, who was active during the 1990s and early 2000s and was well known for her depictions of the female body and female sensuality. Recurrent in her work are warped and amorphous bodies of humans, animals and vegetation, rendered in a simple graphic style in black outline. Erotic content is often explicit and exaggerated, with phalluses, vaginas, breasts and sexual penetration rendered unsparingly.

Sasmita’s work is contemporary in that it takes a posthuman feminist stance; besides fighting for gender equality, she goes deeper to destabilise the assumptions underlying other binary structures, such as anthropocentric biases, and hierarchical categories of nature and culture, the human and the nonhuman. One nonhuman archetype that Sasmita often taps is that of the snake, which holds great symbolic meaning in Balinese lore and Indonesian culture. Her protagonists are often depicted with snakes encircling them or hybridised into half snake, half-women. In Hinduism and Buddhism, nagas are a powerful semidivine race that can appear as human, a partial human-serpent or a whole serpent. In kundalini yoga practice, the snake is the image of vital energy in the cosmos, and is coiled up at the base of the spine.

Snakes will play a huge part in her upcoming work in the Thailand Biennale in Chiang Rai. It will be a quasi- shrine to feminine energies – a circular structure with 900 braids of red ‘hair’ (made from rope) hanging from the ceiling. The red hair is inspired by the story of Draupadi, the main female protagonist in the Mahabharata. In certain adaptations of the story, she washes her hair with her brother-in-law Dushasana’s blood in revenge, after he had molested and tried to disrobe her in public. Referring to the purifying nature of righteous anger, the end of every sinuous blood-red braid in Sasmita’s work culminates in a snake head made of brass, connecting justice-seeking vengeance with a symbol of divine energy.

Citra Sasmita’s work can be seen in the Bienal de São Paulo through 10 December, the Thailand Biennale from 9 December to 30 April, and the Biennale of Sydney starting 9 March through 10 June