In her new show, the artist has defaced Gustave Courbets and made Venn diagrams for understanding sexual violence. What is she trying to show us?

A Central London gallery entirely carpeted with issues of The Guardian sounds like satire, or a far-right fever dream; perhaps that is precisely the point. For Claire Fontaine’s exhibition, visitors remove their shoes and tread across headlines, images and ads for the new iPhone, feeling the numbing glut of media underfoot. The installation, Newsfloor (The Guardian) (all works 2025) transforms the exhibition space into a mutable surface of shifting texts and images, with sheets of the newspaper pasted directly on the gallery floor, layering the ground with the detritus of our media and culture. In doing so, it situates Claire Fontaine’s practice within the very conditions it seeks to interrogate: the entanglement of politics, capitalism and representation. The floor, dense with printed matter, sets the tone for a show preoccupied with visibility and complicity, foregrounding a tension central to the collective’s work; namely, how to make critique visible without perpetuating the mechanisms it seeks to oppose. Across two floors, lightboxes, paintings and sculptural works test this problem, with varying degrees of success.

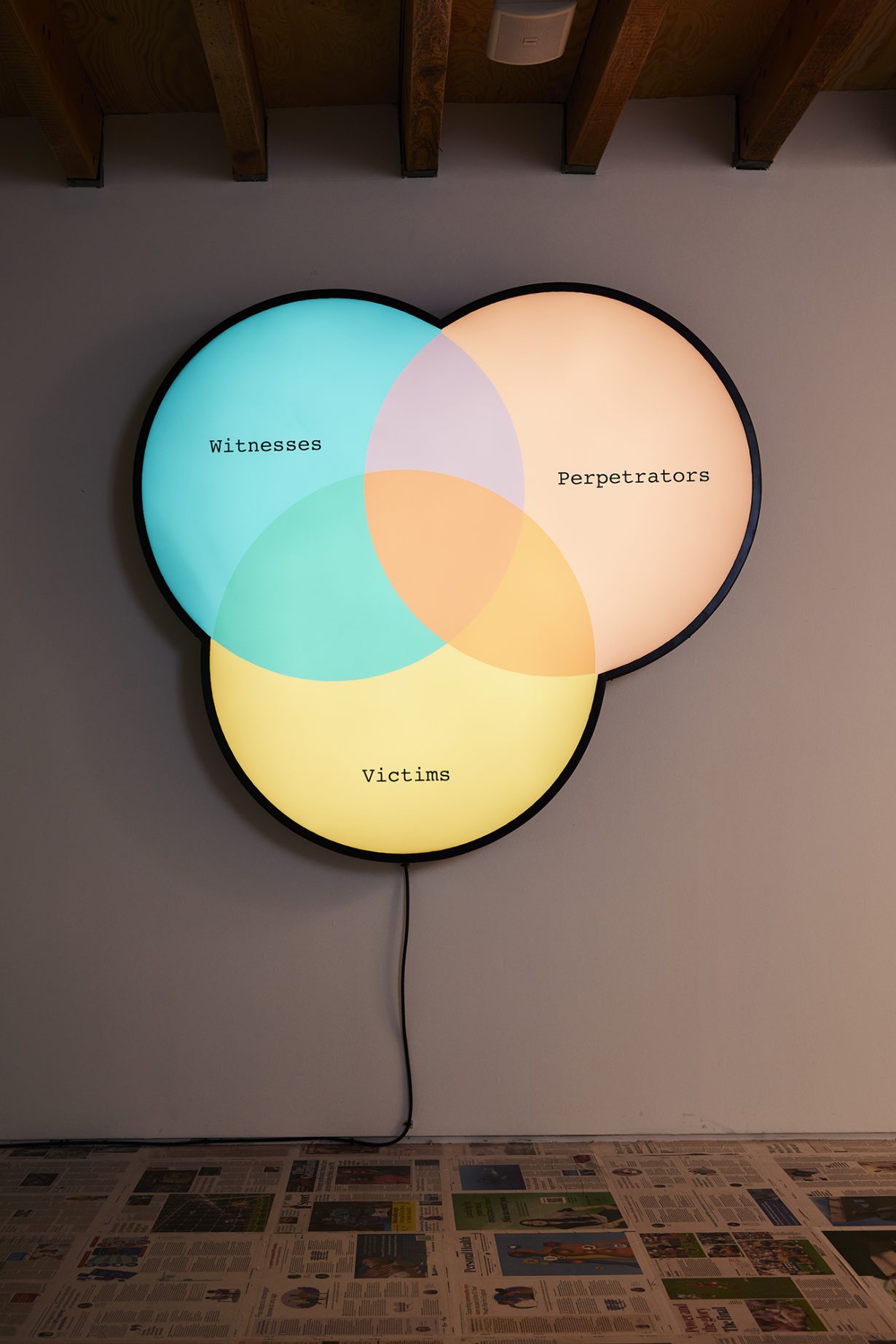

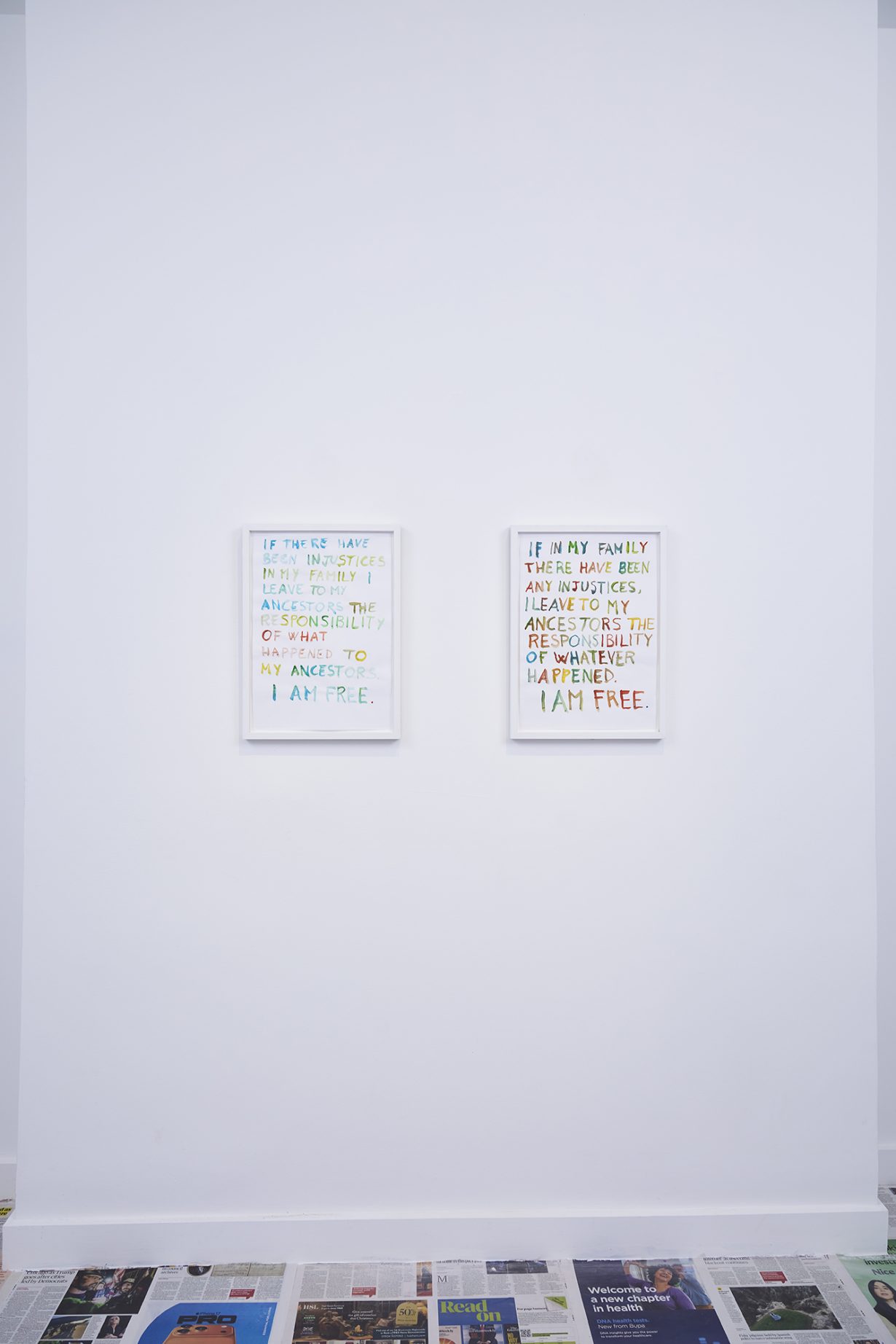

Intersections, a Venn diagram-shaped lightbox inscribed with the words ‘witnesses’, ‘perpetrators’ and ‘victims’ in each of its intersecting planes of blue, pink and yellow, suggests otherwise. The work addresses gendered violence yet feels superficial, its cold, polished aesthetic reducing the complex relations of harm to a neat geometry, tempting viewers to question whether these categories can ever be clearly separated, but its moral provocation is made blunt and unconvincing through its formal precision. By contrast, I am free introduces a confessional register of responsibility within the realm of affect and inheritance. Across 12 framed, crumpled sheets is the repeated phrase ‘If in my family there have been any injustices, I leave to my ancestors the responsibility of what happened. I am free.’ The bleeding colours and creased surfaces proffer a ritual of release that is never complete, the work reframing responsibility not as a moral choice but as a condition that resists resolution, evoking wider debates over whether historical trauma – personal or social – can ever be fully discharged.

But the exhibition hits its stride on the upper floor, where the series L’origine du monde presents 12 reproductions of Gustave Courbet’s infamous eponymous 1866 painting of a woman’s lower torso and genitals, with each reproduction defaced with daubs of spraypaint. The exposed vulva remains, however obscured. The paint, at times diffuse and almost decorative, weakens the violence of its own gesture, turning the defacement into a form of quasi-embellishment. This slippage between aggression and ornament lies at the heart of the work’s effect: the image refuses to vanish beneath the haze of colour, as an unyielding trace of the historical male gaze. Seen in the context of recent protesters’ paint-throwing attacks on canonical artworks, the work invites comparison to those acts of vandalism that blur the line between radical protest and censorious intervention, questioning how those gestures of resistance can reproduce the very dynamics they seek to break, confronting the impossibility of dismantling visual regimes without reanimating them. To this end, Claire Fontaine embraces contradiction as a working principle. Show Less achieves its heft not through reconciliation but through the friction it sustains, allowing tension itself to become the measure of critique. Alexander Harding

Show Less at Mimosa House, London, through 6 December

From the November 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.

Read next: Cosima von Bonin’s works are dumb. That’s the point…