As the country stirs to life, galleries are staging a mix of shows that range from the politically engaged and critical to the don’t-worry-be-happy

At 12:19pm on Wednesday 22 April, Plaifon Amsarika, an aspiring nineteen-year-old artist making ends meet as a Bangkok security guard, posted a pencil drawing of Thailand’s prime minister, Prayut Chan-o-cha, along with an aggrieved message, on Facebook. ‘I drew it in a fit of depression, having no money to buy milk for my child,’ she wrote. ‘I drew it in a fit of depression that I worked 12 hours a day and yet I have nothing left. I drew it with tears…..’ It was a quiet expression of trauma amid the financial devastation of the COVID-19 pandemic. Too quiet, it transpired – seven days later she killed herself.

While the lights were off at Bangkok galleries over the last three months, most oddly laconic even in the online realm, it was emotive, politically vexed imagery like hers – not official artworks – that circulated and stimulated dialogue and debate, both within the city’s somewhat cloistered art scene and out of it. And understandably so. The collective socioeconomic trauma being felt in Thailand – which, in epidemiological terms, is a success story, with 58 deaths, 3,162 confirmed cases and a compliant, mask-wearing populace – is painfully real. The country, which lacks a strong welfare system and relies on tourism for 20 percent of its GDP, is tumbling into a recession that may see the worst unemployment since the end of the Second World War. Meanwhile, since the lockdown began here in late March, the Samaritans of Thailand have been receiving between three and five times the normal number of calls to its suicide helpline.

Further raising the already torrid temperature have been some commemorative, performance art-style protests that are arguably prismatic manifestations of mounting economic, as well as long-standing political, discontent. In early May, photos of the message ตามหาความจริง (‘search for the truth’) being laser-beamed onto buildings around town at night appeared on social media. It quickly emerged that the Progressive Movement – a civic organisation formed by the disbanded Future Forward Party – had staged this public intervention to mark the tenth anniversary of the Thai army’s May 2010 crackdown on Red Shirt protests, during which 94 people were killed. And two days ago, activist groups marked the 88th anniversary of the end of absolute monarchy by reenacting the momentous occasion in front of the city’s Democracy Monument. They also reconstructed the memorial plaque marking the revolt, which had disappeared – part of a trend of vanishing Thai monuments.

One could fairly ask why an exhibition roundup is being prefaced by a crudely abridged sketch of betrayal and erasure, both in terms of democracy and social justice, but the rationale is simple: as Bangkok’s galleries rub the sleep from their eyes, there is a conspicuous split between exhibitions that feel vitally invested in, and those that feel breezily disengaged from Thailand’s overflowing wellspring of sociopolitical trauma.

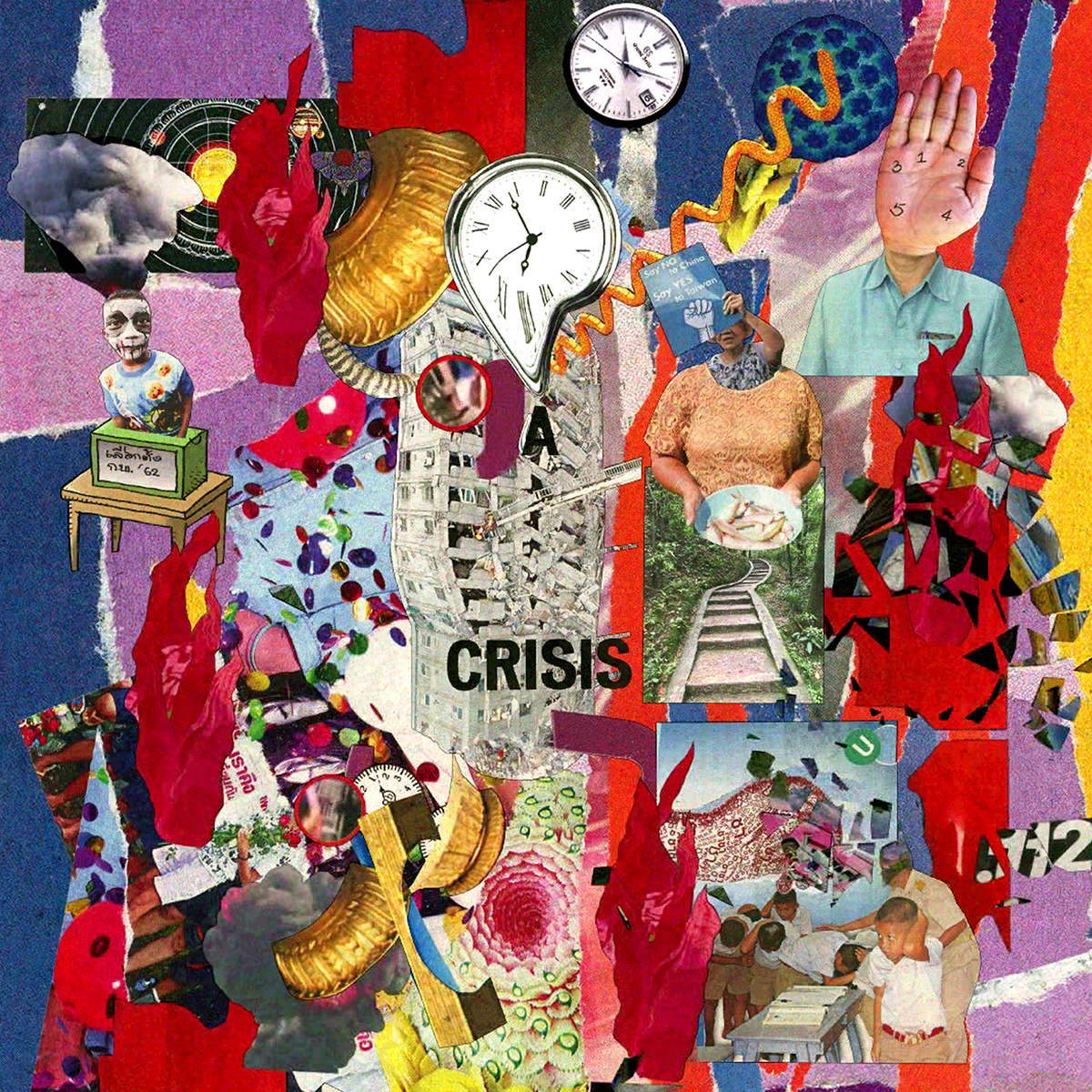

Now on at Bangkok City City Gallery, Chulayarnnon Siriphol’s Give Us a Little More Time is the most vociferous of the former group. Ensconced in a wall of industrial sound and spoken word, his rabble-rousing 12-minute animation manically catalogues the depredations and absurdities of autocratic rule and media control. Symbols of bureaucratic inertia, hypocrisy and doublespeak, drawn from years of newspaper cuttings, which he started collecting on the first day of the latest military coup, create a pulsing, Monty Python-esque parade of belligerent text and retina-scorching imagery. Flowing across four channels, its sarcastic messaging and deranged atmosphere of mounting menace bludgeons you into a sort of enjoyable submission.

More tongue-in-cheek effrontery can also be expected from Conflicted Visions Again, WTF Gallery’s forthcoming followup to a 2014 exhibition that brought together Thai artists of seemingly irreconcilable political persuasions. Marking the tenth year of the mercurial bar and gallery space, this timely restaging will chart the ‘evolving political attitudes of a polarized society’ through works by Sutee Kunavichayanont, Manit Sriwanichpoom, Pisitakun Kuantalaeng and Miti Ruangkritya, among others.

Courtesy the artist and WTF Gallery, Bangkok

At VS Gallery, a new addition to the N22 art complex, Across Eras draws pointed sociopolitical comparisons between now and the late 1970s and 80s through a display of Paisal Theerapongvisanuporn’s surreal and disturbing paintings. And at Chiang Mai’s MAIIAM Contemporary Art Museum, British photographer Luke Duggleby’s all too timely conceptual documentary series, For Those Who Died Trying – a prepandemic leftover also showing online – continues. Why ‘all too timely’? Three weeks ago, a dissident critical of the Thai government and monarchy, Wanchalearm Satsaksit, was snatched off a street in Phnom Penh. Because of this, the insidious issue of extrajudicial killings and forced disappearances – the subject of Duggleby’s elegiac series – has again bubbled to the surface. In each low-slung image, framed portraits of murdered or missing human rights defenders appear in the exact location where they were killed or last seen alive – presence is searingly juxtaposed with absence.

Completing the current roster of exhibitions are some that, instead of being shaped by partisan beliefs, or circumscribed by national borders, are more universal, more hopeful, although their quality varies widely. In recent days, I’ve wandered into a couple that felt so far removed from our current reality as to seem sneering (although perhaps through no fault of their own), including the Bangkok Art & Culture Centre’s 9th White Elephant Award painting and sculpture exhibition, The Land of Smiles – all neotraditional agrarian fantasias, beatific smiles and mystical venerations of Thailand’s three pillars (nation, religion, monarchy).

Others have felt fortifying. Notable in this regard was Elvire Bonduelle’s Vacances Mécaniques (Gallery Ver), where her assisted readymades – garden chairs, sunloungers and trickling water features – fashioned out of Thailand’s ubiquitous blue PVC piping created a playful microcosm of domesticity and holiday time, replete with game time. And Kamin Lertchaiprasert’s ongoing “ ” (Nova Contemporary; appointment only) strives for a weightlessness of consciousness through a spare mix of Daoist poetry, ink and landscape paintings and sculpture, to soothing effect.

Meanwhile, the big news is that the Bangkok Art Biennale will, surprisingly given the dire prospects for international tourism for the foreseeable future, go ahead in late October. Tasked with articulating the accommodating premise Escape Routes is a list of Thai and international artists that now includes Yoko Ono and Thai indie filmmaker Pen-Ek Ratanaruang, among other big names, as well as rookies. During the inaugural edition, CEO and artistic director Apinan Poshyananda was, despite the backing of a corporate sponsor that has benefited enormously from its coziness with the then-military government, keen to stress the social or political nature of many works. So it was surprising to hear him, during the live press conference on June 15, hinting that things might be different this time. “Healing is what we need and desire right now,” he said. “Isolation has made people want to have warmth, and I think coming to see art together with friends, family and loved ones is going to be a phenomenon. We want people to come and appreciate art in terms of giving, compassion, empathy and hope.” We can only wait and see, but given that the anti-establishment Bangkok Biennial –budget-less, curator-less and theme-less – is set to fall at the same time, and that the economic situation here looks likely to worsen before it improves, it seems safe to assume that an almighty clash of artistic missions and messaging, political strategies and sensibilities, is in the offing.