The artist’s speculative, research-driven tools challenge received narratives of migration, labour and environmental history

Of the more than 200,000 maps that comprise the David Rumsey Map Collection – an archive of world cartography housed at Stanford University – a large proportion are of North America, made between the sixteenth and twenty-first centuries. Of the roughly 140,000 that have been digitised, about 60 represent the state of California, a search reveals: there’s a pioneering engineer’s pen-and-ink and pencil map, dated c. 1880, of the Los Angeles–San Bernardino Basin; a forestry expert’s lithograph map, dated 1881, plotting the distribution of redwood forests; an illustrator’s jocular pictorial map, dated 1945, ‘hitting a few high spots of California’s history’; and a geologist’s topographic map, dated 1982, of its coastal mountain ranges. And yet, despite the dizzying thematic and stylistic diversity of the David Rumsey Map Collection’s many maps of California – each testament to a legacy of exploration of the American West by white settlers – only one appears to have been drawn up by an Asian American: Connie Zheng’s How To Make a Golden State (2023).

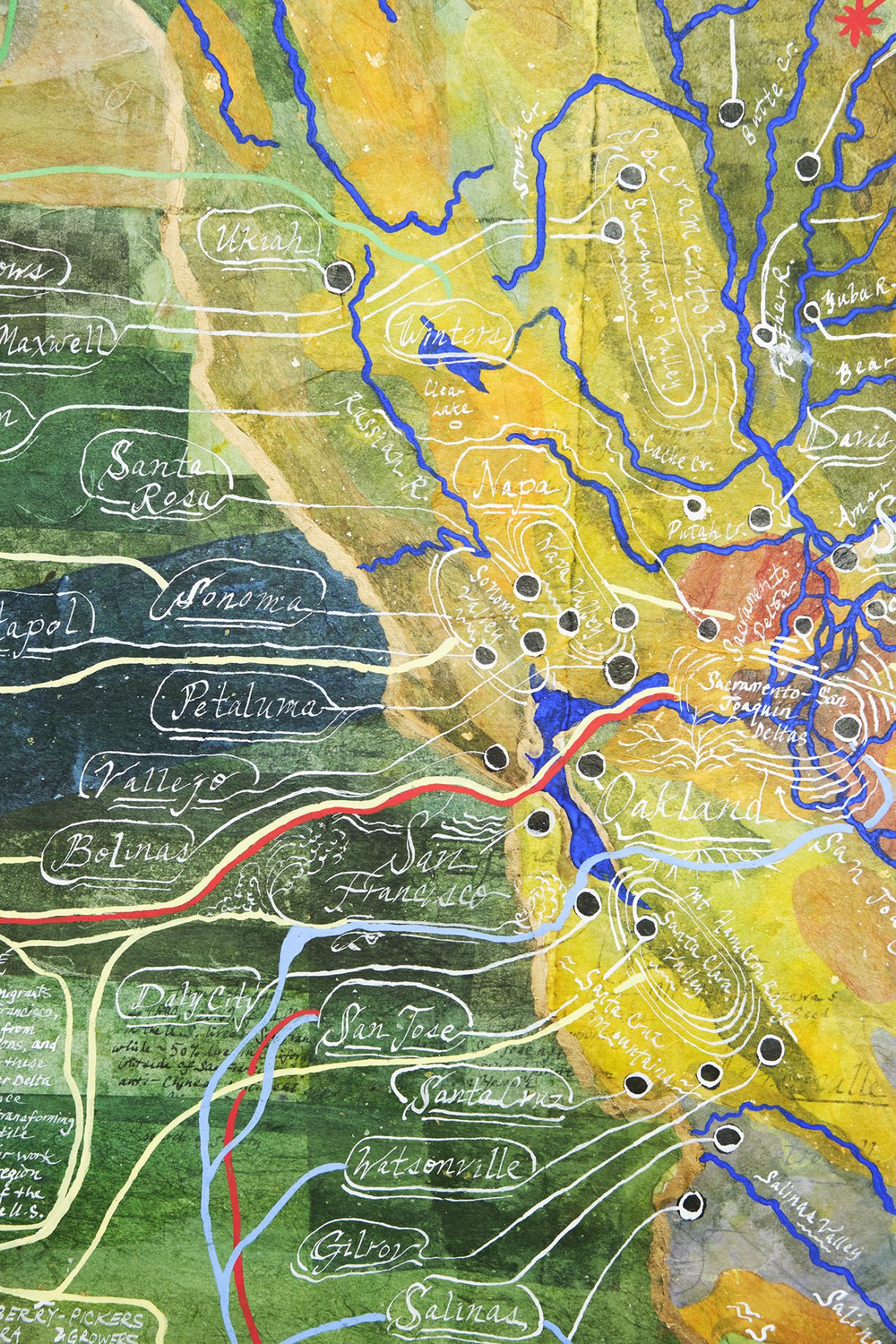

Measuring almost three metres wide, this mixed-media map on rice paper fuses palimpsestic, semiabstract mark-making with a surfeit of handwritten annotations. Across its layered surface, factoids about the contributions of East Asian, South Asian and Southeast Asian farmworkers to California’s agricultural development – each enclosed in a speech bubble and plotted to a location and ethnic group via a colour-coded legend – are joined by the innocent impressionism of the backdrop’s farmland vista and crude clouds, as well as a disclaimer. This map is ‘nowhere near exhaustive’ and ‘admittedly incomplete’, Zheng explains in fine handwriting, nor does she ‘mean to elide or ignore the massive contributions of Latinx- and Chicanx-Americans’, who ‘form the backbone of the farm industry in the Golden State’.

But while the tone of her notes for reading this map is circumspect, even apologetic, her anecdotes are forthright. These serve to trace both the trajectory of Asian immigrants in California’s farming industry since the late 1800s – their ascent ‘from being field hands into the landowner class’, their travails in the face of ‘intensifying white resentment’ and more general suspicion of Asian others during the Second World War, their alchemical transformation of barren land into success stories – and this trajectory’s overlap with us labour history. While researching the piece, Zheng tells me, she found that “many of the biggest organised labour actions and farm strikes in California were actually led by Asian workers” – a discovery that complicates the “mainstream normalised narrative of Asian workers as invisible, as silent, as deeply marginalised”. Her map of California plots this secondary narrative with the same alacrity as it does the first. ‘Starting in the 1930s, white growers began to fear Filipino workers,’ begins one caption.

Based in Berkeley, Zheng is a multidisciplinary artist who has recently found her calling in the research-driven making of maps, some of which centre the experiences of Asian Americans. Yet her biography, practice and interests defy neat labels such as ‘Asian American’ or ‘mapmaker’. Between 2017 and 2019, while doing an MFA in art practice at the University of California, she began making work that “dealt with the ways in which the rhetoric around environmental catastrophe is heavily racialised and classed, especially in the United States”.

Notes on fluorescence (2018), a video essay from this period, situates this interest within the context of her childhood – a childhood that saw her moving to the US in 1993, at the age of five, then spending summers visit-ing family in the heavily industrialised Chinese city in which she was born, Luoyang. Ruminatively, the film explores the “emotional and psychological whiplash” that ensued, her seesawing between opposing political systems and national narratives, by contrasting footage documenting one such trip with reflections on the US media’s portrayal of China as a toxic place. But while Notes on fluorescence conveys something of Zheng’s whiplash – her solemn voiceover toggles between ponderings on her “slow acculturation into this narrative” and the US’s “own psychologically and materially toxic activities abroad” – she now considers it anxious and didactic. “I was angry and grumpy when I made it, and I think that came through in the work,” she says.

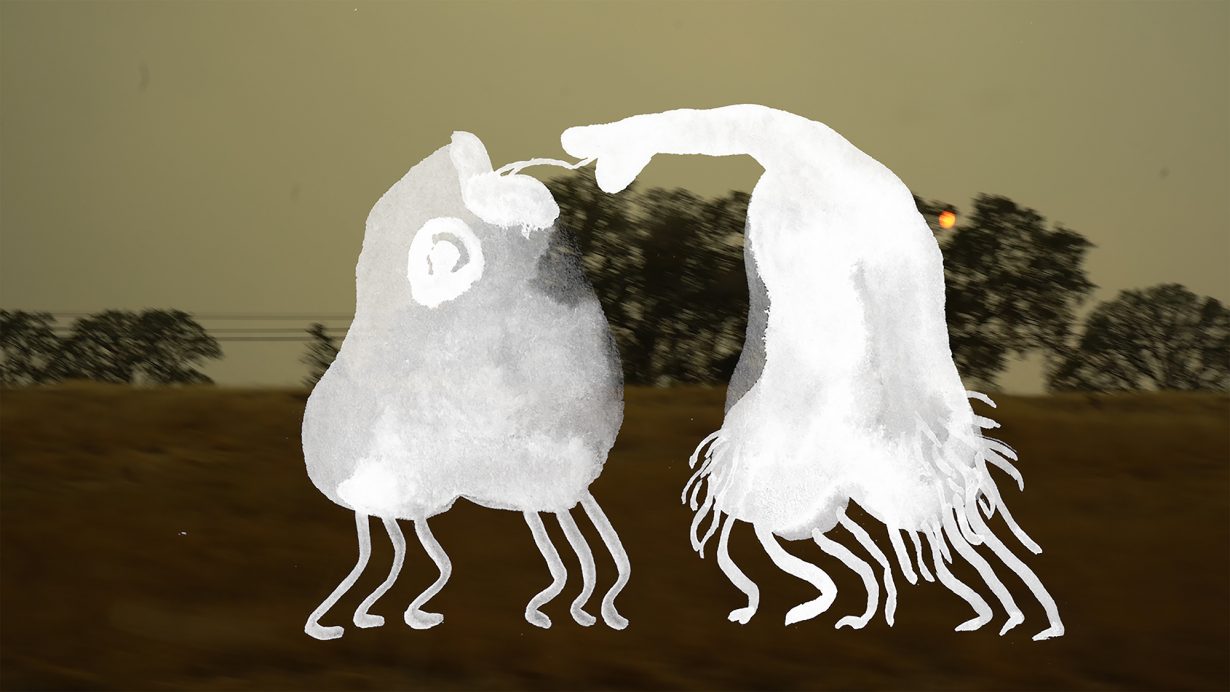

A year later came The Lonely Age (2019), a speculative disaster short that broaches the spectre of ecological catastrophe via improvisation, not a scripted narrative. Joining its cinematic footage of masked figures stumbling through a ravaged landscape, looking for seeds with supposedly curative properties, is a polyvocal voiceover made up of the extemporised responses of 40 collaborators (“Maybe the seeds are invented by the bio-corporations to prevent the total annihilation of hope,” remarks one; “I think that they’re made real by the belief that people have in them,” proffers another). The script Zheng handed them as a means of triggering these responses was part seed catalogue, part survival manual – it comprised her watercolour sketches of imagined seeds, alongside fables and snippets of speculative fiction she herself wrote. The result is a film that circles certain themes – not least the notion of invasive species prevalent within American environmental and racialised immigration discourse (one rumour spoken of is that the seeds came from a Chinese GMO factory) – without editorialising on them.

Since this film was acquired by the Kadist collection, a large number of her projects have centred seeds. Alongside a mid-COVID followup, Seedtime (2020) – a short film that features a similar cast of ‘seed-searchers’ but adds kinetic animations of hand-drawn seeds into the mix – these works include seed-making workshops; a speculative seed catalogue; and Routes/Roots (2021): a world map plotting the migration of food plants over the past few millennia. This output has made its way into installations, such as Seed Almanac (2019–), which featured tables laid with small glass basins containing a primordial soup of live cyanobacteria colonies and clay seeds made by the public: ‘spaghetti-and-meatball seeds’, ‘flare gun seeds’, even ‘heart-seeds for building community’. Another exhibition, new yamfish seed exchange (nyse) (2021), paired Routes/Roots with mixed-media prints of speculative germination sequences. It also proposed a prototype for a different investment ecosystem to that offered by the New York Stock Exchange, one ‘rooted in collaborative imagining and play’ and wherein ‘seeds for the future’, such as ‘cinnamonbird’ and ‘debt cancellation berries’, made up the portfolio.

Asked how she alighted on seeds as a thematic container, Zheng gives a two-pronged answer: a personal reason and a conceptual one. The first has to do with her paternal grandfather, who lives in Fuzhou city in subtropical, southeastern China. While visiting him in 2016, she was shocked to learn that he had been cultivating a rooftop garden since the 1980s. “He had always disappeared for hours at a time,” she says, “and I thought he was playing Mahjong with friends, or out for a smoke break, but then I found out, no, he actually crawls through this little cupboard in the kitchen, up a shaft into his garden.” This discovery of “a space of interiority within someone I thought I knew” (as well as a lush urban oasis in which pomegranates and papaya flourish) created an affective link with plants and led her to start growing – and working with – them.

The conceptual reason can be summed up in the form of the questions she asked herself after receiving some negative feedback to Notes on fluorescence: “How can I open up conversations with both myself and viewers of my work around environmental and ecological catastrophe? How do I start these conversations and open space for that dialogue in a way that feels hopeful?” Seeds are, she explains, the perfect conversation starter because they “do a lot of symbolic heavy lifting without you having to explain a whole lot”.

This statement gets at a self-reflexive tension in her work. A tension that could be glibly described as resting upon Zheng’s past inclination to explain “a whole lot”, but would be more accurately, and fairly, described as consisting of an ongoing negotiation between competing wings, or facets, of her practice: the rigorously erudite on the one side, and the avowedly self-expressive and dreamy on the other. In aesthetic terms, the latter wing seems to be winning. While early works often flagged up research and namechecked thinkers, her imbrication of seeds with notions of co-creation and survival has tempered these excesses and, simultaneously, placed her among a long lineage of contemporary artists who have seen seeds as receptacles of meaning and potential.

One can see a similar dynamic playing out in the evolution of her maps, the creation of which has recently superseded other facets of her work and forms another oblique answer to those questions about how best to open up conversations within herself and others. In these maps, we find a steady, incremental move away from aerial maps with heavy text elements towards more experiential and mental mappings. Maps that are guided by stories, sense data and an urge to steer the viewer towards a new understanding of, or perspective on, a local community or ideological issue – a sort of speculative wayfinding – rather than geospatial data or careful citations. Maps that “infuse familiar spaces with a sense of alienness”, as Zheng puts it, but remain legible.

Strawberry Fields Forever (2024) is another community-based representation of the experiences of Asian farmworkers, but one that deploys an alternative semiotic language to that found in How to Make a Golden State. Instead of a legend not found on orthodox maps of California – a detailed caption about the Hmong farmers of Fresno, the pinpointing of a Chinese hop-picker strike, etc – the viewer finds a painting with subtle cartographic elements. A street grid of the small city of Watsonville can be made out, just, but its dreamy terrain also includes the faces of farmworkers and relief prints of fruits and vegetables. For Zheng, this mapping of her interaction with the heritage of the Filipino immigrants, or ‘Manong generation’, who settled in the Pajaro Valley is a topography of personal anecdotes and oral histories – and a directional signpost. “I see myself continuing to experiment with a cartographic language that is more embodied,” she says, “and much more in conversation with the feeling of places that are so thick with change.” Recent largescale works pair this sense of experimentation with a certain prismatic quality: each reflects something of the multitudes that, to paraphrase Walt Whitman’s line, Zheng contains as an artist. While some of her maps, as well as rolling projects such as Decomposition Notes (2021–) – a daily stop-motion record of plants in her garden – represent ways of thinking about the diasporic relationship to home, she emphasises, during our conversation, that her relationship to identity politics is ambivalent. This is particularly the case when it comes to the “Asian-American performance of identity” driving a lot of artistic production in the United States, especially in the Bay Area, where she lives. Partly because she has “never really felt Asian American” (her “whiplash” included being homeschooled in Chinese using textbooks featuring Mao and Lenin while being taught that “China is the eternal enemy of the United States”). And partly because she sees a danger of artists being pigeonholed, or “self-Orientalising”.

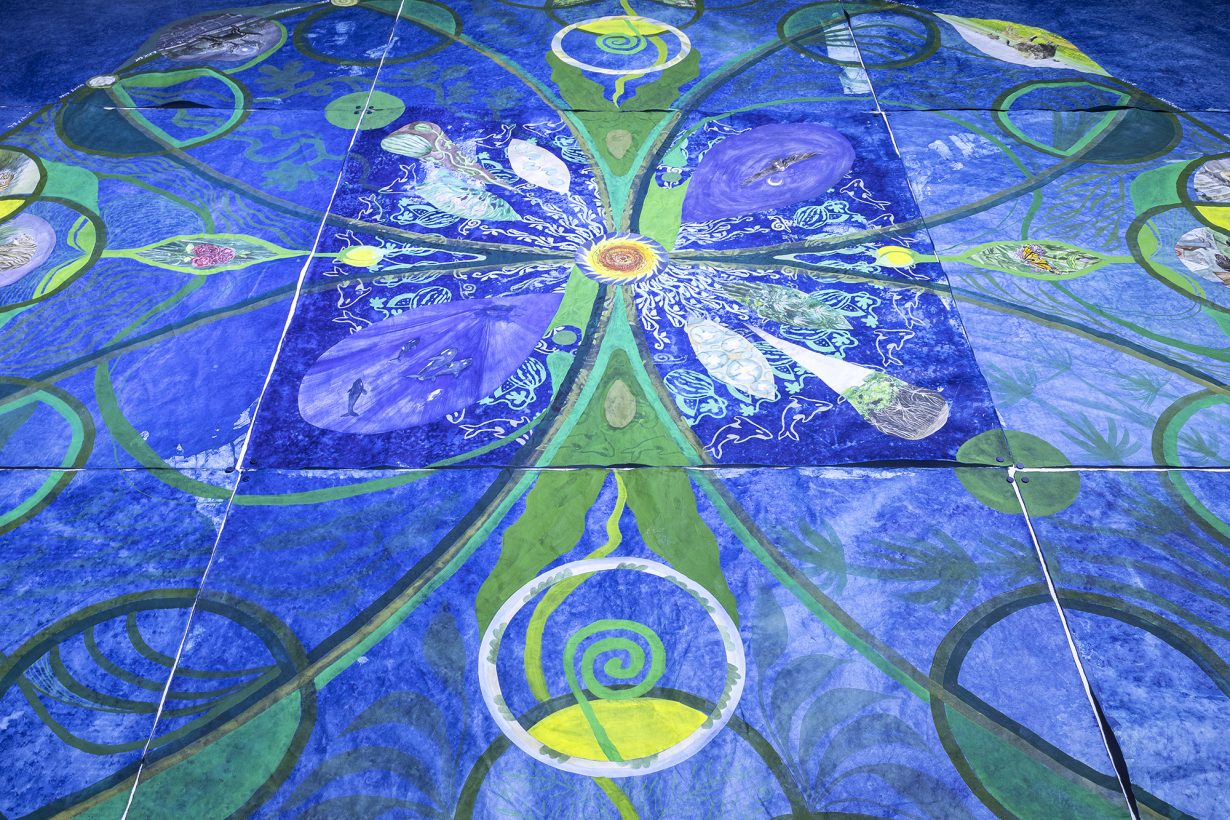

Two works currently on show seem to ward off these dangers, as they stake out a broader range of concerns and sympathies. As It Is: Nothing Lasts Forever (2025) is a collage of intaglio and cyanotype prints, measuring four-and-a-half metres in length, that evokes and comments indirectly upon the awe of the unfathomable. From a distance, we see a deep blue, heliocentric solar system wherein geometric shapes excitedly orbit a many-pointed sun. But on closer inspection it is a cartographic representation of market forces – its dots denote corporations as well as ‘living beings’ and ‘minerals/ natural resources’ traded ‘as commodities in the open market since the sixteenth century’, the succinct legend states, while its lines (which create a web of connections between entities) signify a ‘clearly documented extractive relationship’. Created for a group show about the persisting global legacy of the plantation system (The Plantation Plot at Ilham Gallery, Kuala Lumpur), it is a piece that induces dual sensations: disorientation and wonder. It gains its air of mystique and infinitude through an esoteric visual language grounded in Zheng’s expansive realm of interests: theosophic abstract art, Ancient Chinese star maps, a fascination with the rhetoric of capital that was triggered by a shortlived job in financial services. “I wanted this map of capitalism to feel astronomic and almost spiritual,” she says, “because that is the way finance and the market is spoken of in neoliberal countries. I strongly believe that the United States is a theocracy and its god is capital.”

Another large work on paper with a cyanotype backdrop, Revolutionary Planting Calendar (2025) is a seasonal planting calendar of the mildly mystical, post-Haight-Ashbury type you might find in, say, a homespun health-food shop in the Bay Area. Although fresh produce is not the subject matter at hand – it charts what Zheng calls an “efflorescence of revolutionary and liberatory multispecies symbolism”. Each plant or animal depicted is associated with an emancipatory movement: the watermelon to Palestine, the monarch butterfly to the US-Mexico border issue, the snail to the Zapatista uprising of 1994, etc. Together, these vignettes form an elaborate circle of kinship, or a florid cartography of hope – one that serves as a fey response to creeping authoritarianism around the world, and ties into the theme of Manifesto of Spring, a group exhibition at the National Asian Culture Center in Gwangju that seeks to ‘present future-oriented agendas for democracy’.

Numinous works like Revolutionary Planting Calendar augur a more distilled approach, one that speaks, it seems, to a growing confidence. Zheng’s process of making each of her maps always “starts with a question” and always entails finding “the affective space of this question”. But whereas previous works found their answer in dense overlays of text – elements that betrayed the vast amount of research she gathers and metabolises – her latest lean into abstract form and the tactile aspect of her practice. Currently doing a PhD in visual studies, she is acutely aware of the dangers of being too situated within the academy. “I want my practice to be in a constellation with theory, not to illustrate it,” she says. Her habit of drawing doodles and handmaking everything herself forms an “anchor point” that serves to mitigate this risk. “I process my own film. I process my stills. I hand-draw animations,” she says. “It’s very slow and laborious, but I think I need to be in that daily practice. The ritual aspect of being in contact with material every day is, I think, what gives a lot of work, not just mine, life and poetry.”

Her handcrafted surfaces also communicate, nonverbally, her attunement to the state of the world – a sensitivity that is nourished by the musings of others (cultural and academic terminology, from ‘survivance’ to ‘slow violence’, and invocations of lineage still litter her own essays), but grounded in time and space by residencies, during which she conducts preparatory sketches and takes walks “to get a sense of the chromatic language of a place”. And their material imperfections and subliminal vibrations also serve to communicate, subtly, her thoughts on maps writ large. Echoing Polish-American philosopher Alfred Korzybski, who pointed out that we should not mistake maps for the territory or thing they claim to represent, Zheng says she wants to foreground how “subjective my maps are, and how biased I am as the maker in order to reference the fact that most maps are not objective at all”.

Manifesto of Spring (featuring Revolutionary Planting Calendar) is on view at National Asian Culture Center, Gwangju, through 22 February

From the Winter 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.

Read next How to wipe colonialism off the map