The late American novelist transformed blood and horror into sublime visions of the American West through the prophetic power of language

When the news broke that American author Cormac McCarthy was dead at 89, leaving behind him twelve novels, five screenplays and two plays, the immediate reaction from his many readers and fans was to share the passages of his writing that meant the most to them. Oblique in their intricate mysticism, woven with made-up yet intuitively correct words (‘razorous’ being my personal favourite), McCarthy’s descriptions and images always read as if he had summoned them from somewhere beyond himself and placed them upon the page unedited. In fact, this couldn’t have been further from the truth. McCarthy did famously edit and often worked on multiple projects at the same time.

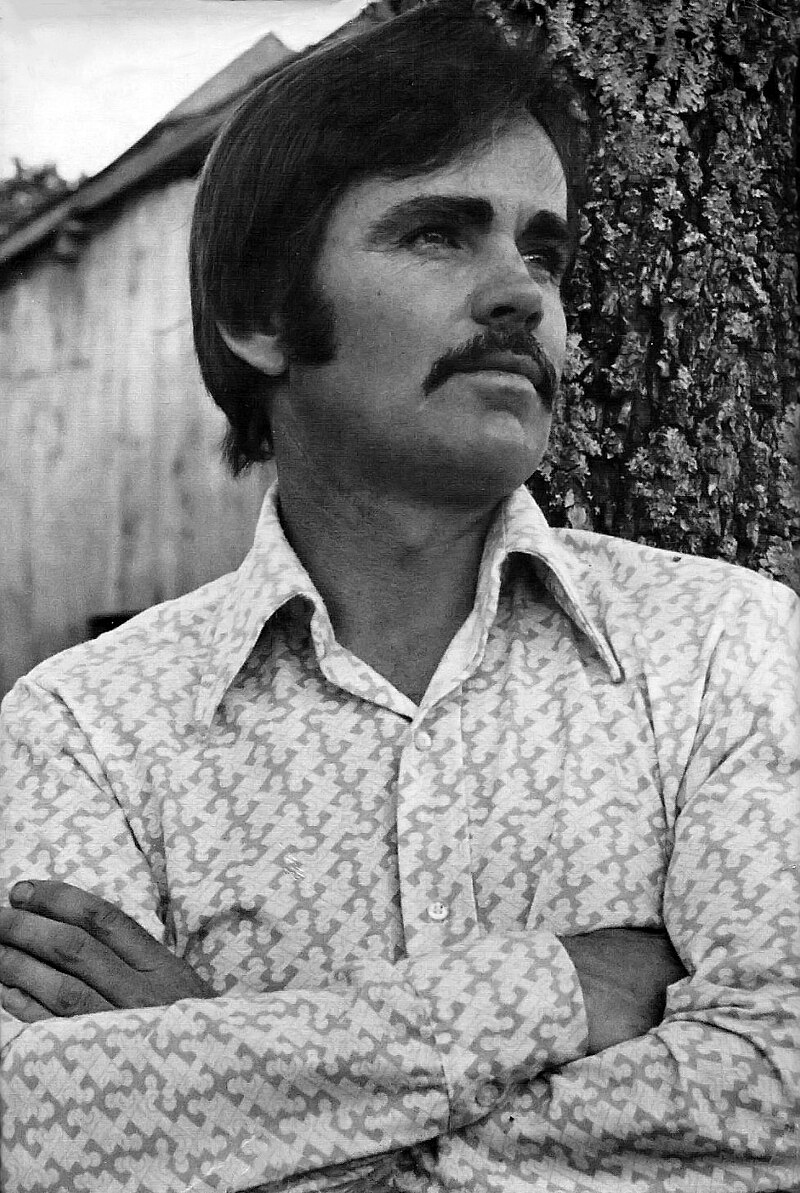

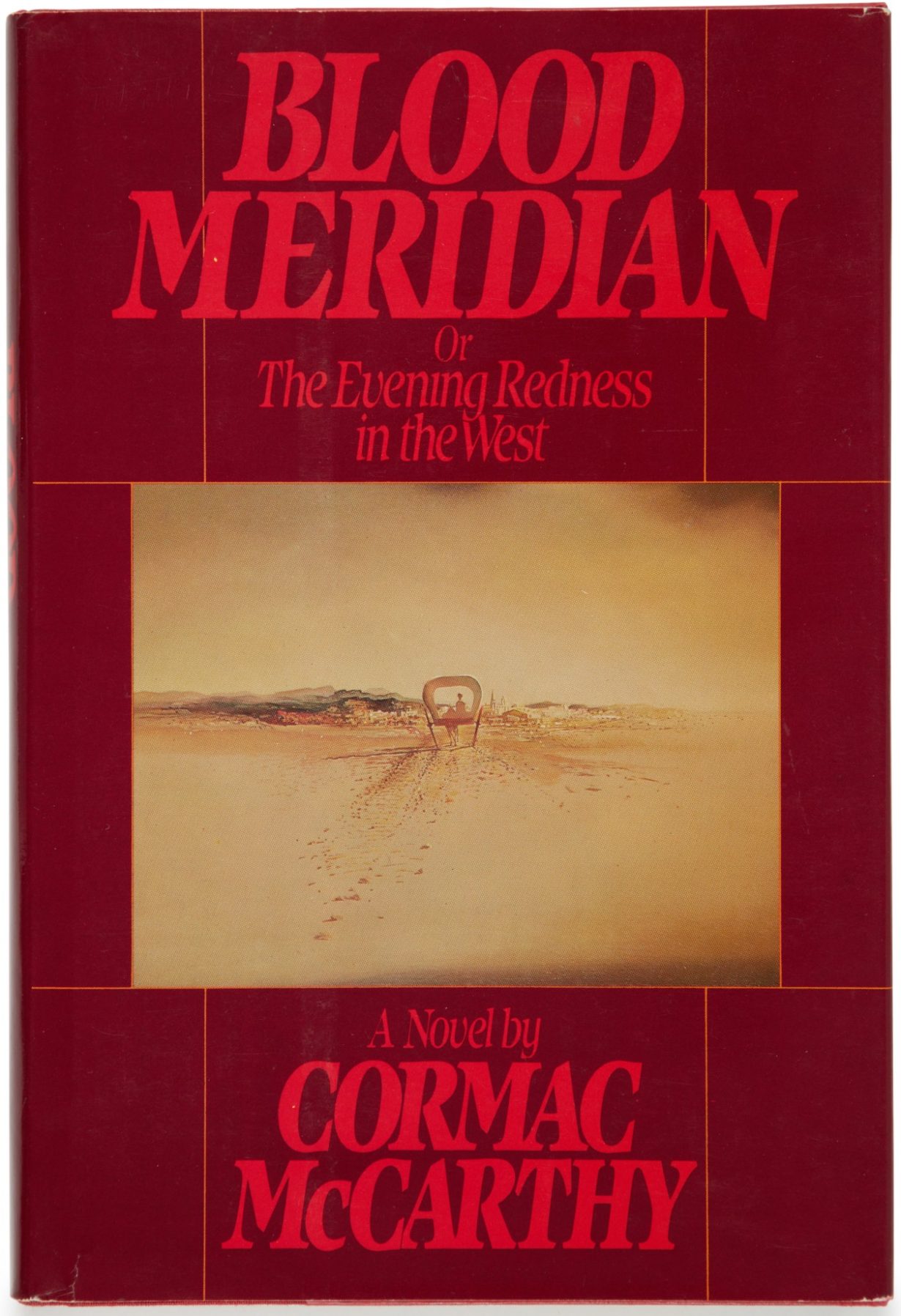

There is a temptation to build mythologies around writers, to understand the process of their work as a kind of magic: the single-minded commitment to writing (so much that he and his family – he had three wives and two children throughout his life – often lived in poverty in the earlier years of his career, into his thirties, as he refused to work other jobs); the typewriter on which McCarthy superstitiously wrote every word for fifty years; the breakthrough of winning the MacArthur Grant in 1981 when he was 48, allowing him to research and write his fifth novel Blood Meridian (1985), a work drenched in gore and presenting a searing revisionist version of the American West.

These generalised cultural mythologies of McCarthy’s process and dedication seem unnecessary when held up next to the prose of one of our greatest fiction stylists, though it makes sense that we would try to understand where the power of his sentences came from through whatever means at our disposal. ‘All things of grace and beauty such that one holds them to one’s heart have a common provenance in pain’, he wrote in his postapocalyptic novel The Road (2006): sentences sometimes concise and other times twisting into bewildering complexity.

Born in 1933 in Rhode Island, McCarthy moved to Knoxville, Tennessee at the age of five, going on to study physics and engineering at the University of Tennessee, before dropping out to join the US Air Force, where he ‘read a lot of books very quickly’ to counter the tedium. Another mythology: the light bulb he carried around with him whenever he travelled away from home, to ensure he could read wherever he went. Blood Meridian, often regarded as his most important novel due to the acclaim it has since garnered, initially received only a lukewarm critical and commercial response. It wasn’t until his sixth, All the Pretty Horses, published in 1992 when he was just shy of 60, that his work began to find larger, more commercial audiences.

Reading a McCarthy passage can feel like being picked up, held in the air, filled with adrenaline as you zoom out on a landscape precise and unfamiliar, not quite sure where the sentence is taking you until its end. The Biblical cadences, the immersion in words and structures and rhythms that in the hands of other writers would seem unworkable, absurd even. They are the passages of someone working with total confidence, visionary not just in the act of form, but in their view of a how things are – the world itself as ‘a hat trick in a medicine show, a fevered dream, a trance bepopulate with chimeras having neither analogue nor precedent’ , as he wrote in Blood Meridian.

With little punctuation and descriptions veering from stark to baroque, twisting and taking the reader towards the unexpected and impossible, the experience of reading becomes visceral in itself. It becomes one of image and feel and intuition, an experience of the body, maybe even (let me be earnest here) of the soul. If we are grappling with these huge questions – life and death, good and bad, the vitality of hope and its (frequent) absence – do we not also need prose which aims suitably high, toward an altered experience, an altered vision, somewhere beyond what we know?

These novelistic worlds, these fevered dreams and trances – be it Appalachia, the old West, the ruinous landscape of our own, horribly recognisable future – are united in nihilism. They are worlds abandoned, worlds hurt by ourselves and by forces within and outside our control, worlds with a new internal logic. In these worlds, language dives into the abyss and comes up with something like treasure, something transcendent. Look into the void, a McCarthy novel seems to say: isn’t it terrible, and yet still beautiful there? It’s life and death and nothing less, somehow simultaneously expansive and distilled. Everything and nothing, as far as the eye can see. As far as it is possible to articulate the void with language, and perhaps find meaning or even a kind of comfort in it, McCarthy grasps for it – and takes hold.

This determination toward beauty in the face of utter devastation feels particularly acute in The Road, which was where I first encountered his work. I still vividly remember the experience of reading it, aged 17 – the staccato rhythm, the desolation of the landscape, the unimaginable horrors rendered right there on the page, so much that I sometimes had to put the book down, that I experienced physical jolts of nausea at the vivid descriptions of atrocity.

And yet the prophetic weight of the language – how vividly it articulated McCarthy’s vision of ‘the absolute truth of the world. The cold relentless circling of the intestate earth. Darkness implacable’ – made me long to create sentences like this and think about the ways in which I could: sentences which could call up the impossible, that held a deep and solid rightness in them even as they spoke of unbearable bleakness. For when the book is finished, what you are left with is the tenderness rather than the shock, the enduring love rather than the end of everything and the infinite darkness after that. I sought not only to create these sentences for their own merit, but dared to probe that abyss itself, or at least to take a look inside; to think about humanness as he did, in large scale and as it manifests in the small and everyday; to not find it an absurd or too-large endeavour, but to see it as intrinsic, as the necessary thing.

Sophie Mackintosh is the author of novels The Water Cure (2018), Blue Ticket (2020), and Cursed Bread (2023). The Water Cure was longlisted for the 2018 Man Booker Prize