People hate Apple’s new iPad Pro commercial. Is it because they love art?

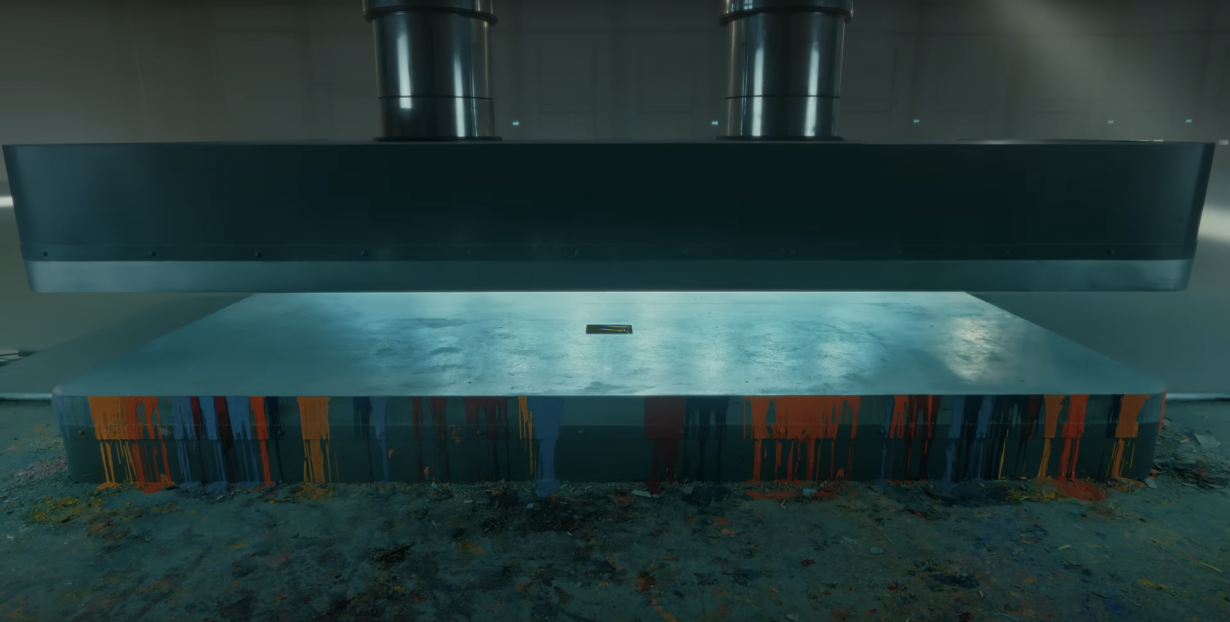

It starts with a metronome ticking, then a record player whirs into life. Sonny & Cher’s ‘All I Ever Need Is You’ (1972) plays as the lights come on in a large, empty industrial space. In the middle of the room is a huge hydraulic press with an impressive array of objects organised on it as if it were a stage. There are tubes of paint, a piano and a microphone on a stand, a bust and a globe, a full bookshelf and two mannequins – the small wooden kind used by artists, and the full-size one that fashion designers have. Sonny sings, “Sometimes when I’m down and all alone…” as the press begins to descend, crushing a trumpet standing atop an arcade game. ‘Game Over’ appears on the screen.

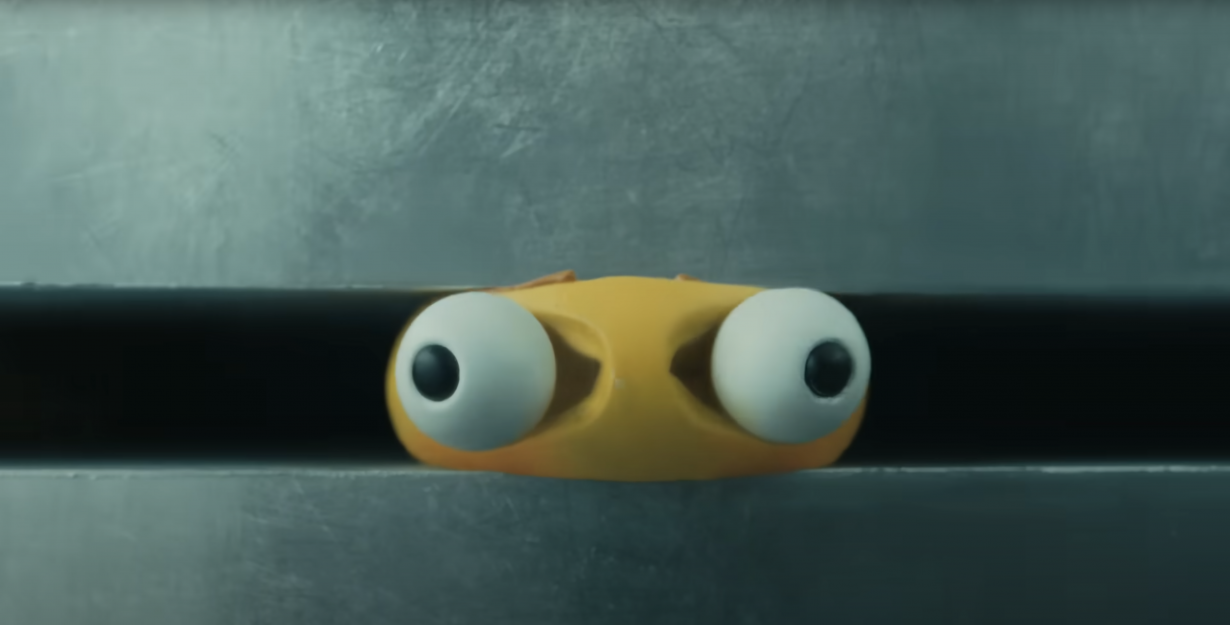

The song then jumps to the familiar bridge, “All I ever need is you…” and the upbeat tune accompanies the destruction, as the hydraulic death-trap comes for a model of one of the Angry Birds and a guitar’s strings pop under the tension. A Flushed Face emoji stress ball falls from a pyramid of other emoji balls to become the press’s final victim as the machine reaches its base and the ball’s eyes pop out before it is annihilated. When the press begins to rise again, it reveals an iPad where all those objects were. A woman’s voice says, “The most powerful iPad ever is also the thinnest”. And Sonny sings again, “All I ever need is you”.

Apple CEO Tim Cook posted the video on Twitter/X, adding, ‘Just imagine all the things it’ll be used to create’. Does he mean the trumpet and piano, the paint and brushes, the guitar, the metronome, the books, the cameras with multiple lenses – are all folded into the iPad? And anyway, who even has an iPad? An iPad is so sleek, so far from the bland utility of some black, plastic laptop. But then, I remember when the first iPads came out people joked they were just big iPhones: it’s hard to tell what an iPad is really useful for – most of its functions can be just as easily achieved on a laptop, a phone or some analogue device. And so, it’s been assigned to the realm of ‘creativity’, because if it’s not that useful, perhaps it’s closer to art. This slick fancy object feels more practical for a salesmen flicking through images of something expensive (A flat? A car? A curated vacation?) that they’re trying to sell you on than, say, a band playing around collaboratively with Apple’s GarageBand (the name itself hinting at the creativity that Apple then appropriates, packages and sells back to us wrapped up in a glass case).

People don’t like the commercial. The response to the crushing and shattering of instruments of art and culture has been compared to book burning, to censorship, to dystopian visions of the future. Hugh Grant tweeted, ‘The destruction of the human experience. Courtesy of Silicon Valley.’ A number of users performed the classic, here-I-fixed-it-for-you trope we all want to see: if you reverse the video, the press rises, the spilt colours congeal, Mr. Stress Ball’s eyes pop back into their rubber sockets and the artist’s mannequin slowly rises back to its legs, as if stretching in relief. One of these versions is set to the tune of ‘I Got You Babe’ (1965), also by Sonny & Cher.

None of this is new. Users were quick to point out a 2008 commercial for the LG Renoir phone (‘enhanced with 8GB of memory’!) looks very similar, with paint spilling and cameras being squashed into an image of the blocky early smartphone. And anyway, TikTok is full of hydraulic presses crushing things, from household objects (a decorative porcelain of a hedgehog, a stack of plates, candles) to foodstuff (eggs) and an iPhone. These videos are often tagged ‘ASMR’ and classified under ‘satisfying things’, a proof that in a culture of excess there is gratification in destruction. A user crushing an iPhone feels like a result of a culture of excess, perhaps you could even argue a rejection thereof, but when Apple does the same thing, it feels telling.

Advertising execs would tell you the vitriol directed at the spot means that it’s good – that it sparks a conversation, which is the goal of advertising. But the anger is exactly about this relationship to creativity; and this commercial lays its cynicism bare. Apple has branded itself the company of design and artistic sensibility – Just imagine all the things it’ll be used to create – and the crushing is not a betrayal of these ideals, but proof that Apple does not think of its products as facilitating human creativity. Squashing the artefacts of creativity is a way to narrow access to it: this commercial tells us it’s time to change how we think about art, that it comes out of a shiny device, not a human mind.

For Apple, “to create” is a form of leisure, not of art or culture. In order to convince us that we need to pay for luxury devices, Apple made creative work aspirational. So, a band in the garage is nothing without GarageBand, and a cool urban architecture studio doesn’t need blueprint paper and drafting tables when it can have an iPad in a modernist pseudo-Scandi office. These images of how culture is made are the contemporary imagination of creative work, and Apple played a central part in the creation of this perception. In this world, a pen and paper (or an iPad Pro and a Magic Pencil, which alone retails £129) cost almost £1500 – because creativity comes at a price.

Orit Gat is a writer and art critic living in London