In late 1978, London saw a slew of exhibitions presenting German art from the Weimar era – the ‘Neue Sachlichkeit’ (New Objectivity) movement – alongside exhibitions showcasing contemporary artists working in the then-divided West Berlin.

Writing ironically about a German ‘invasion’, Arts Review’s Pat Gilmour was nevertheless enthusiastic about the quality of the art on show. At the same time, her essay also considered the politics (and money) working behind the scenes to bring these shows to London, which saw the Whitechapel Gallery’s then-director Nicholas Serota publicly at odds with the ICA’s curator Sarah Kent.

At a time when West Germany was keen to project its international profile and cultural leadership, Gilmour considered how the sponsorship of even ‘radical’ art exhibitions can end up further legitimising the interests of power. Rather than censor radical artists, Gilmour concludes that the modern state ‘gives its artists, even those at issue with it, a cultural subsidy. Thus even as they denounce it they simultaneously proclaim leviathan’s superior liberality and defend its unrepentant self-perpetuating power.’

‘The New Objectivity’ is the usual translation of Neue Sachlichkeit. Objective, however, is hardly the adjective I would choose either to describe the intense penetration beneath the surface of deadpan engine rooms and hallucinatory household objects in its ‘magic realist’ branch, still less the frenetically mordant and coruscating satirical indictment of Weimar Society between 1919 and 1933. This, the ‘Verist’ group would have us believe, was entirely composed of pimps and prostitutes, profiteers, policemen and paupers.

If art were able to change the world, or even an occasional heart, surely this vehement, committed figurative painting, the message of which few could fail to understand, would have opened men’s eyes to error and paved the way to the millennium? But no. Frank Whitford in the ICA’s ‘Critical Realist’ catalogue relates that not only was this avant-garde art doomed to preach to the already converted through the inevitable narrowness of its circulation, but the more prurient drawings by Grosz, Christian Schad and Jeanne Mammen were actually used to illustrate A Guide to dissolute Berlin describing the fleshpots of sexual perversion where transvestites, lesbians and homosexuals could be bought. Worse… far from being redeemed, society swapped the Weimar Republic for Hitler and the Third Reich. Will we ever be able to believe again that it is enough for art, or anything else for that matter, to observe, to depict and be able to say afterwards: ‘Well, I told you so’!

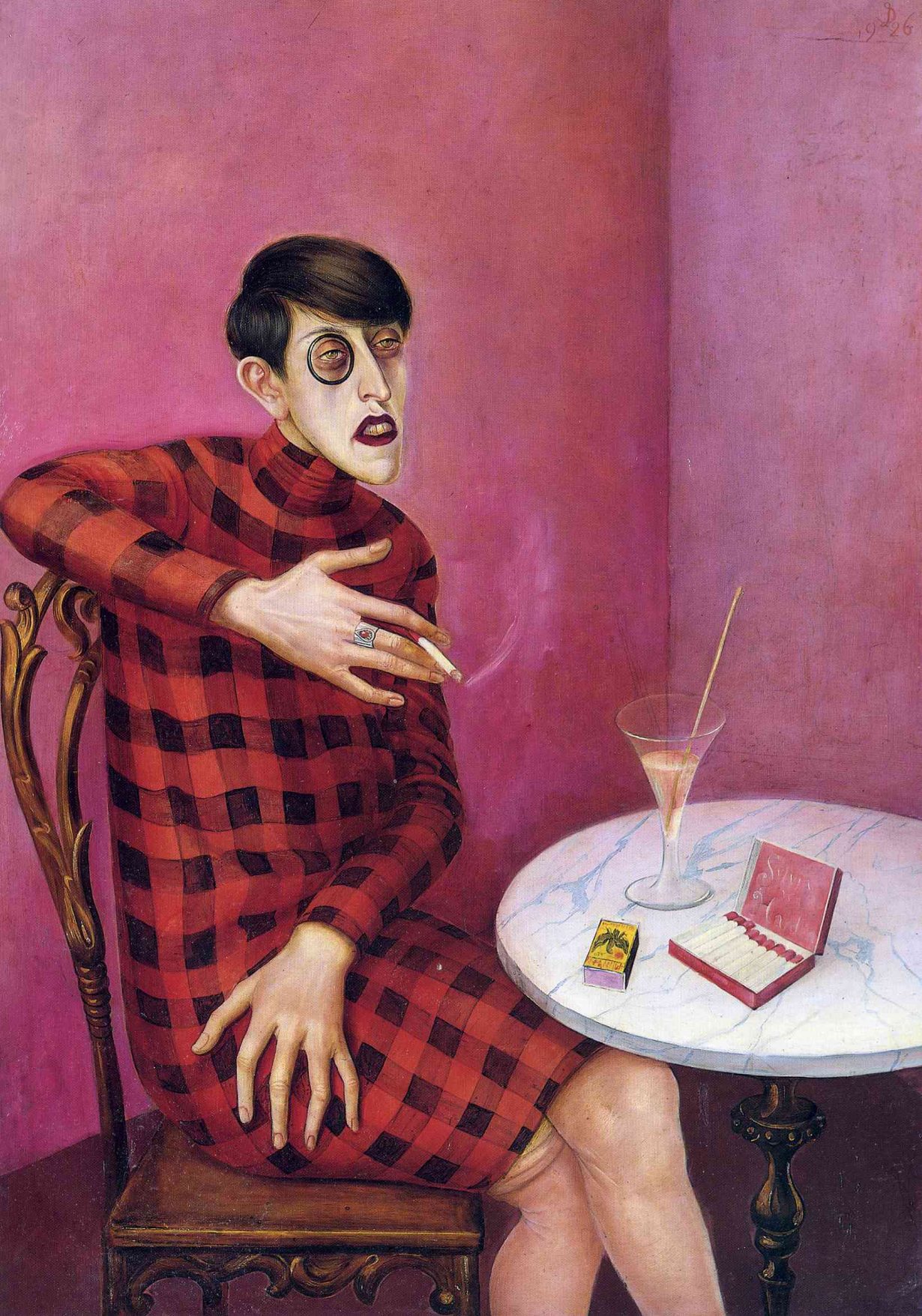

However, if one can disentangle aesthetics for a moment, and strip the art from its context as all well-brought-up art historians are expected to do, this is an amazing display of painting, printmaking and drawing. Grosz and Beckmann one knew about, but Otto Dix has never been seen here in such profusion and his is a sly and wicked talent. Three Prostitutes on a Street sum up his savagery: a blonde floosy ogling from under a coal-scuttle hat over a fox fur, a scrag end of mutton trying to soften unredeemably hard features with a red veil, and a gold-helmeted snob with upturned nose clasping a Chihuahua to her capacious bosom. Breasts depicted by Dix only burgeon or sag, and his varicose veins make Lucian Freud look like a non-starter. His portraiture is equally devastating. Frau Ey is a suffused sandbag, Herr Krall is a wasp-waisted twit, and only the poet von Lücken is viewed more tenderly, with his cascading hair matched by the scrolls of a church outside and his height echoed by a spindly rose. Christian Schad’s penetration into type is equally remarkable, each specimen presenting a strange implacably quietist yet simultaneously exotic vision of humanity.

In Tottenham Mews, Annely Juda pulls a strong oar in this cultural bonanza presenting the witty but more formalist collages of Hannah Hoch, the subversive but somewhat introverted Dada of Baader and Hausmann, and some prints and later watercolours to extend our view of George Grosz: all the work is well documented in an illuminating catalogue.

At the ICA the view of contemporary Berlin is of ‘urban, capitalist living with the skin of glamour peeled back to expose the emptiness of many people’s lives in our modern cities’. Twenty-one painters, sculptors and photographers and 15 film-makers together create a stark composite view. Hermann Albert shows brassiered blondes in plastic apartments admiring their uplift; Maina Miriam Munsky records with clinical detail moments of life or death in the alienating sterility of the hospital; Sorge juxtaposes images of sex and violence from the media, while every protagonist in Grützke’s pictures seems to be a crazed image of himself.

His largest work, a baroque transcription in which three middle-aged putti hover over a grotesque seance, is at the Whitechapel, where a somewhat different view of Berlin is proposed. Gunter Brus advocates retirement to a monk’s cell to make hand-made books again, and launches a tirade against today’s art, preferring to ‘splash in the brook with the trout children’. Gosewitz dabbles in astrology while Tomas Schmidt analyses utopia with language allied to graphic symbols – charming but a trifle twee.

The ‘conceptual expressionist’ painters, Koberling, Lupertz and Hödicke respectively wax lyrical about seed pods in synthetic resin on jute, construct somewhat pretentious Dithyrambs (which my dictionary defines as inflated poems), or reduce the city to elementals in a way which reminds me of the young Mondrian.

Vostell, famed for the strong political line he takes, has created an environment three parts empty bombast, but one part a forceful statement which would have been capable of equal potency on its own. The implications of the fact that in Germany over 200 details of one’s existence may now be committed to computer is symbolised in a refrigerator full of dead fish with transistor radios strapped to them.

In some ways the furthest-reaching work in any of these exhibitions is the feminist work by a group at the ICA, which they use as a teaching device publicly, and that at the Whitechapel in which Dieter Hacker and Andreas Seltzer propose a new folk art.

Comments by an old lady in the margins of the capitalist press, slogans circulated all over Berlin by a man with a bee in his bonnet about indoctrination, the moving ‘in memoriam’ notice in which mourners remember their mother and sarcastically thank the state for not recognising her as a severely handicapped person until long after her death, are all proposed as an art form possible for ordinary people. If enough people believed they could operate in this way as rebels, perhaps we would be able to change the world. ‘You are standing in the middle of art history’ says a text. ‘Are you part of the action?’ This is a truly subversive work, because it does not merely analyse a problem, but proposed a solution. But how do we avoid the inevitable castration of the gallery situation?

Because art and its relation to politics is explicit in so much of the German art currently assembled in London, it is perhaps interesting to look rather closely at a charge that political power has blatantly controlled the nature of what we are seeing, and has victimised a particular group. In the Whitechapel catalogue, Nick Serota claims that his original exhibition plans (to show 11 artists of the avant-garde constituting something of a Rene Block phalanx) were first approved by Hochschule sponsors in Berlin. Then, after a change in political attitudes at the school (from right to left-wing as it happens), his project was shelved. Instead, says Serota, a prepackaged ‘Critical Realist’ exhibition was offered simultaneously to several London institutions with the promise of up to £65,000 to fund it. According to him, the ICA accepted this offer (ultimately receiving £45,000) while the Berlin Senate refused the Whitechapel either assistance or money. There is a further charge, documented by a letter being issued to Whitechapel visitors, that Grützke, one of the artists participating in both shows, appears against his will at the ICA.

Naturally, there are two sides to every question. Firstly, says Sarah Kent at the ICA, there was no package deal; she was actively involved in selecting her own show, and, in fact, wanted to include several of the artists now showing in E1. When she went to Berlin following the German initiative, she had no prior knowledge of the Whitechapel involvement and on learning of it ‘bent over backwards’ in an attempt to collaborate and share funds. However, several of the Whitechapel artists, who, I’m told, regarded themselves as a cut above reactionary realism, refused any kind of joint collaboration and demanded the money for themselves. (There’s nothing like solidarity, brothers). At this stage, Grützke, who initially committed himself in both places, was asked if he was absolutely sure he still wanted to participate at the ICA and gave assurances that he did. Later a letter saying he had changed his mind was received, but he told the ICA’s German organiser, Eckhart Gillen, that he had been pressurised into writing it, and did not really mind being exhibited in both places. He did not reply to Sarah Kent’s August request for clarification until the eleventh hour; thus by equivocation then delay he somewhat ingeniously subverted political pressure in his own way. It’s significant that where an artist absolutely refused to participate, Vostell for example, his wish was respected.

Although Nick Serota’s catalogue does not reveal how much money he got (only how much the ICA got), in the end both exhibitions were funded by the German state. None of these funds came directly from the Berlin state (which is wrongly implied by the Whitechapel catalogue) but were filtered through various other bodies – the Berliner Festspiele, the Goethe institute, and the Notgemeinschaft. As all true Englishmen will know, when money comes through the arm’s length principle, it cannot be political.

Of course, in truth, it is crystal clear that political concern has occasioned this entire German invasion of England. If specific bias is being claimed, however, it is far from easy to corroborate by means of the Whitechapel work. Indeed, considering its role as the alleged ‘official’ viewpoint, the ICA show, backed up by lectures and considerable documentation (which had to be defended from censorship) gives overall, a far more uncomplimentary view of Berlin. For unlike the Whitechapel, the ICA relates the art it is showing not merely hermetically to other art, but to a broader total canvas; its success in so doing may be measured by the fact that it has been cast both as establishment lackey and left-wing troublemaker.

Why, you may well ask has so much money been spent by the Germans, not only here but elsewhere, to promote their culture? It hinges, I suspect, on the grooming of the Neue Sachlichkeit for the art market big-time and on the strategic importance of Berlin to the West; culture provides the inducement for citizens to remain in a beleaguered and unpleasant city. Not only are German artists seduced by generous grants, but the DADA exchange programme has also lured several English artists to the city, including Stuart Brisley in 1973/74 who (as so many of us do) found himself advertising capitalism in spite of himself. Writing in the ICA catalogue, he tells how he became increasingly aware that he was a pawn in the political game, and that together with other sponsored artists he was supporting ‘an image of West Berlin required for political purposes, which was only incidentally related, if at all, to the needs of the city’.

Undoubtedly art as an ideological tool may have one meaning in its artistic intention and quite another in the use society makes of it. Rather than playing this somewhat silly game of the pot calling the kettle black, perhaps Nick Serota might reflect on the political nature inherent in his own situation. What construction, for example, might be placed on the growing Arts Council support for the Whitechapel (in a city not culturally undernourished) by, say, an unlucky provincial gallery that had failed to obtain finances to support a show of local artists? Might it be imagined that this demonstrated establishment approval and, therefore, political support from his programme of ‘quality’ dealer culture (laced, it’s true, with the odd Pearly Queen photo for the Whitechapel natives)? I’m not grumbling: I’ve been indoctrinated to that somewhat rarefied and narrow view of culture as aesthetics and it has its place. But perhaps it’s high time we radically questioned the basis for our establishment prejudices and the distinctly political implications behind their reinforcement. Pluralism equals freedom?

Open or covertly, here and abroad, political control operates in ways a good deal more subtle, devious, and yes, at times even unwitting, than Serota suggests in his rather naive analysis of the Berlin situation. Perhaps the real lesson to be learnt from ‘The 20s meets the 70s’ is this: Between the wars the State labelled artists degenerate, and forbade them to work. Hitler needn’t have bothered; no one had heard them. Now, being more sophisticated, the State gives its artists, even those at issue with it, a cultural subsidy. Thus even as they denounce it they simultaneously proclaim leviathan’s superior liberality and defend its unrepentant self-perpetuating power.

Neue Sachlichkeit and German Realism of the Twenties was at the Hayward Gallery

The Twenties in Berlin (Baader, Hausmann, Grosz, Hoch) was at Annely Juda

13°E. – 11 artists working in Berlin was at Whitechapel Gallery

Berlin – A critical view, ugly realism 20s-70s was at the Institute of Contemporary Arts