Hirst’s first ever retrospective in Mexico feels like a blockbuster from another time, before the artist became the puppet – and puppeteer – of millionaires and their institutions

Damien Hirst’s first ever retrospective exhibition in Mexico flaunts all the bells and whistles of grand old prepandemic blockbusters. Massive, encompassing all three floors of the snazzy Museo Jumex building, it is brimful of all the ‘greatest hits’ and looks expensive as hell. In that sense, it feels slightly anachronistic too, very pre-vibe shift – that collective worldwide moment when something definitely cracked, for the worse – in the same way that Beyoncé’s recent albums sound like they come from a more prosperous time. But judging by the large crowds attracted like flies to Jumex juice, that sense of disparity continues to be a very enticing experience: who could resist the proximity to opulence, to capital A, Taschen-book Art?

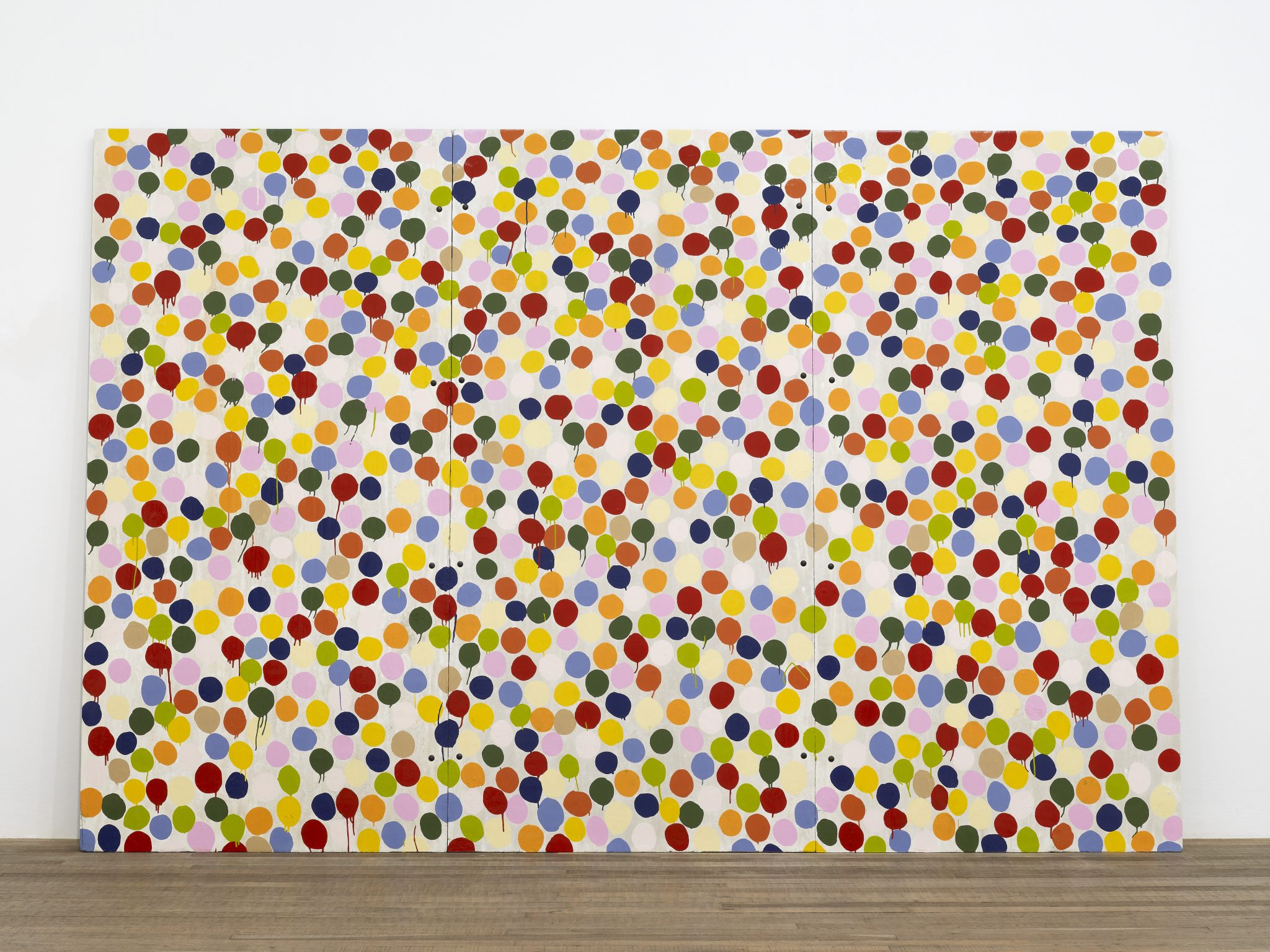

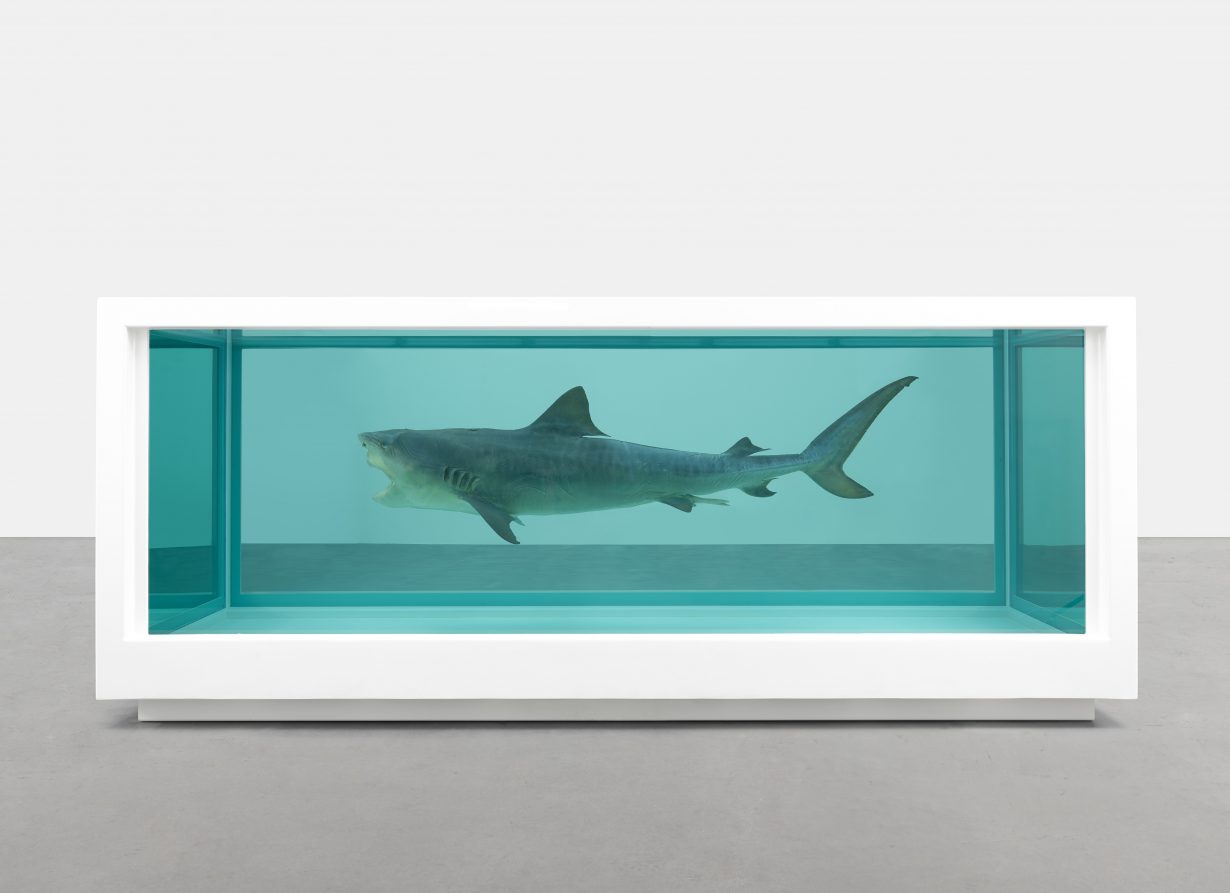

The first gallery is packed with fish tanks from the ‘Natural History’ series. Over here is Stimulants (and the Way They Affect the Mind and Body) (1991), a pair of severed sheep’s heads in glass cubes; over there, Black Sheep (Twice) (2007), two, uh, black sheep in identical sheep-sized, black-framed tanks; in a corner, Away from the Flock (1994), another sheep in a white-framed tank. In the middle, more redundant splendour: Death Explained (2007), the famously bisected tiger shark that allows for excited spectators to traverse its guts; sitting next to Death Denied (2008), another shark, this one whole. The more modest The Impossible Lovers (1991), a neat group of shelves stacked with cow organs stuffed in assorted jars, is a successful, precise piece of work. There’s a twisted yearning, a sorrow in the immutability of their separateness and classification, that seems to embody the whole point of the pickled pieces more clearly. I only wish Hirst’s goth sensibilities were given a bit more space for drama, but the pathos and morbidity of animal corpses and medical utensils is hindered by the overlapping of bodies of work: the ‘Cabinets’ lined with semiprecious stones, and the ‘Dot Paintings’, with grids of fastidiously painted circles of different colours. A main wall presents Urea-13C (2001), a gigantic example of the dot paintings, which carries airs of confetti-filled birthday parties; while the entire back wall of the room is covered in Tears of Joy Wallpaper (2011), a tacky print of variously sized zirconia crystals sitting on golden shelves. Over the wallpaper is hung Judgement Day (2009), an actual gold-plated steel cabinet of massive size whose long, narrow shelves are lined with 30,000 sparkling crystals.

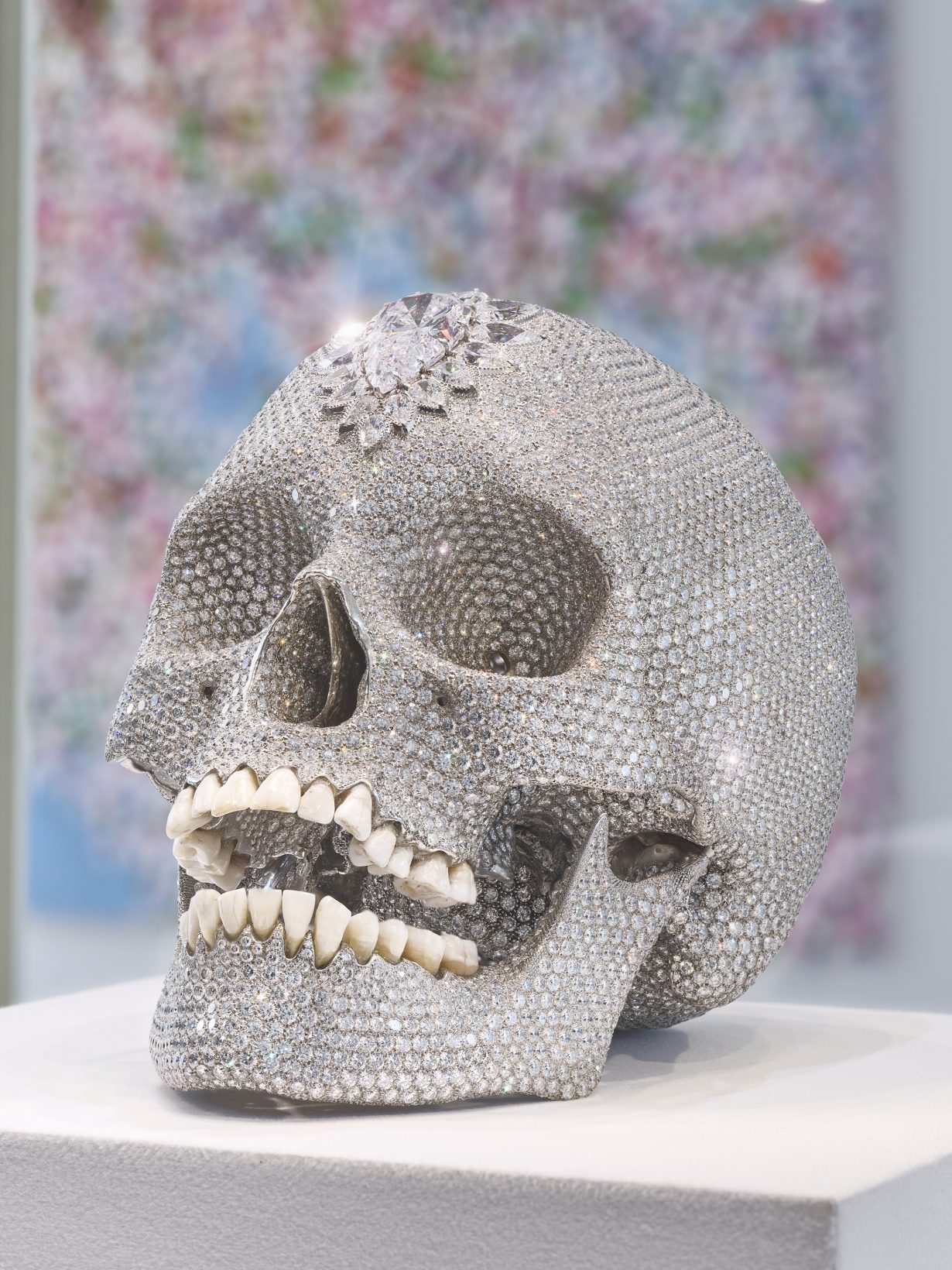

The shiny, pretty rocks would have worked better on the second floor, where many of the ‘Butterfly Paintings’ hang. Anoint (2016), with its moody, unsettlingly symmetrical composition, is a definitive highlight, its near-monochromatic dark palette evoking a void except for bright intrusions of colour on the dainty insect’s wings; as is Hades (2008) with its rich, earthy tones provided by the extremities of monarchs and moths. Perhaps a contrast between the prosaic value of the zirconias and the ephemeral poetry of butterflies could have articulated something, but alas this room was already crowded with more animals in formaldehyde: a bisected cow and calf (Mother and Child [Divided], 1993), three soaring geese (Up, Up and Away, 1997) and four more sharks (Theology, Philosophy, Medicine, Justice, 2008). The third floor is total whiplash: Hirst’s recent ‘Cherry Blossoms’ paintings, made of jejune blotches of luridly coloured oil paint, served as the vaudeville background for the central attraction, For the Love of God (2007), the famous platinum skull spangled in real diamonds. it is hard to say more about this room, except that it is perhaps the most grotesque one of all.

The show evinces a link between early Hirst, his earnest inquiries into the ultimate mystery of life, aka death, and the naivete of his later, more garish work. The continuity of juvenile gestures growing in value would seem especially evocative and lucid for the man-children of the extreme upper echelons of our society, advancing the belief that the accumulation of diamonds, buildings and art collections can ultimately achieve transcendence and cheat death. This narrative seems to have, sadly, overpowered Hirst’s original goth ardour, extinguished its nihilistic, kid-who-just-found-Sartre depths. It could be simply a matter of taste and how it is shaped today: millionaires and their institutions love nothing more than a flashy work of art, but perhaps not so much to have it remind them of their imminent demise, so they pay enough to flip its purpose, turn it aspirational. It is now so expensive, so ostentatious to own or show a Hirst, that it has become a symbol of the grandeur of those who do, of their importance that will undoubtedly extend in time. The joke is on the sharks; decomposing (for decades, or for a few years, depending on which batch you’ve purchased), silly scapegoats for deathlessness through wealth. Maybe it was always a joke, an expensive one, and it’s for sale.

To Live Forever (For a While) at Museo Jumex, Mexico City, through 25 August