Brathwaite-Shirley’s videogame installations ask us to confront our own demons, leaving us – ‘the players’ – questioning who we even are

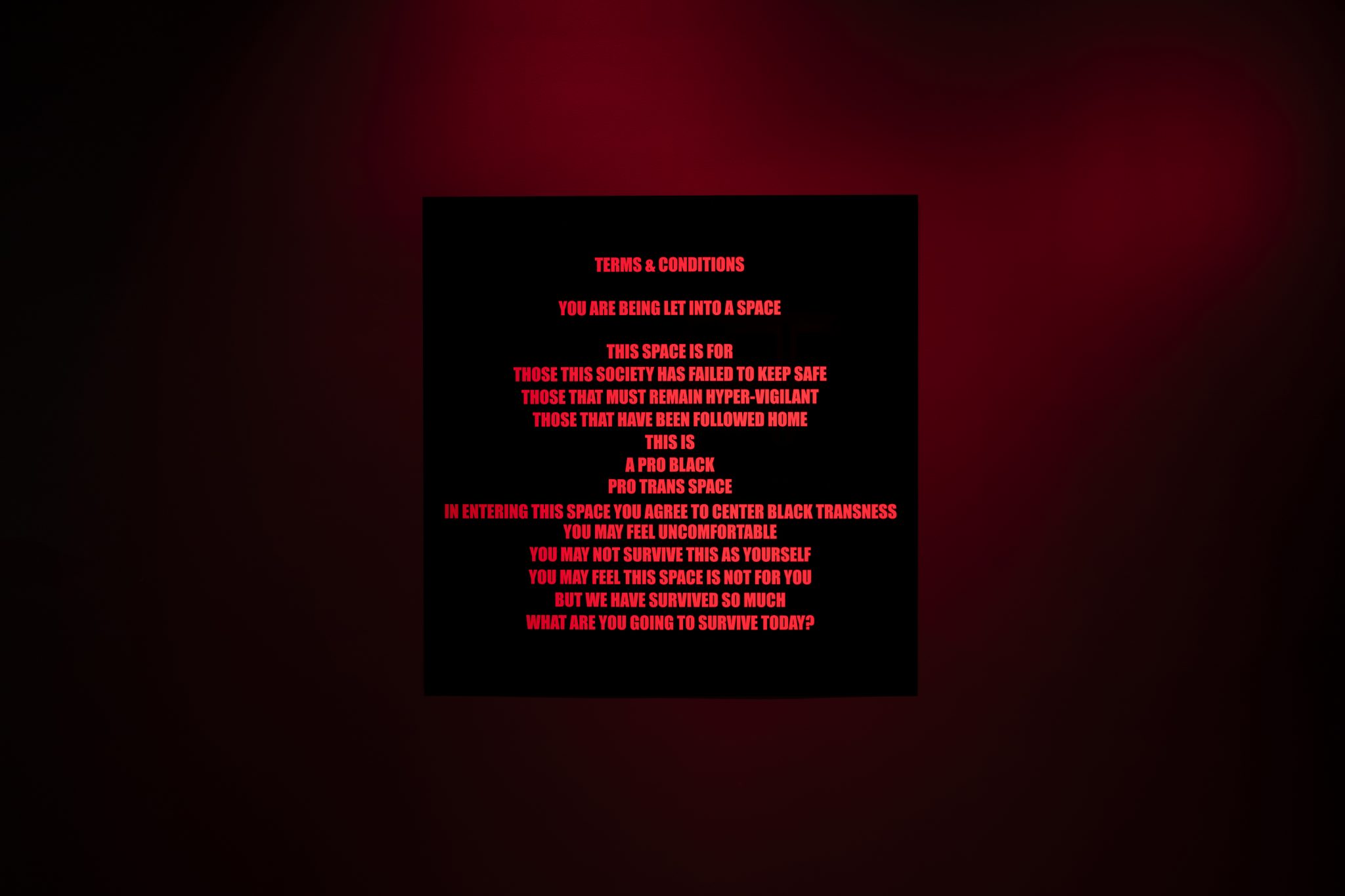

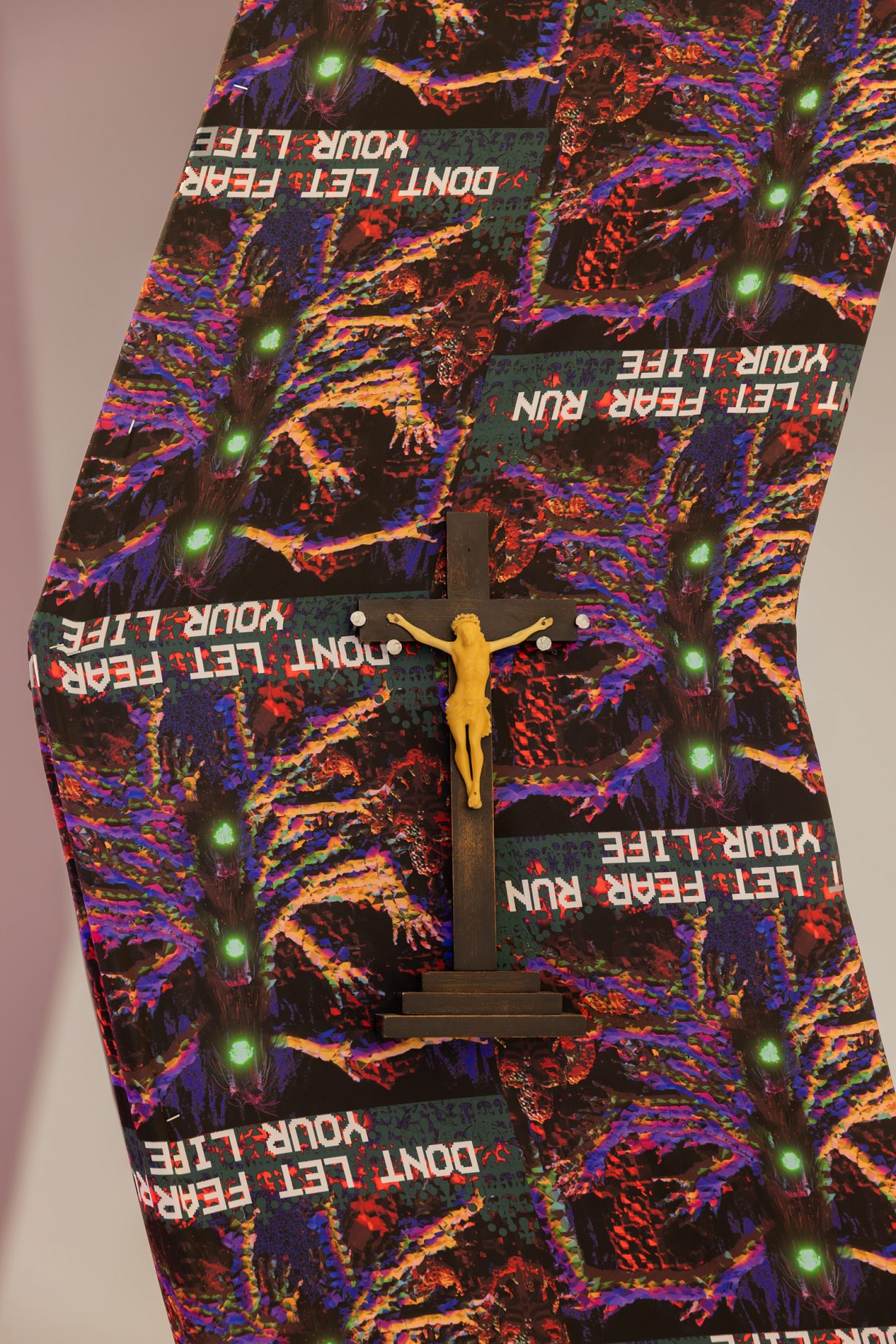

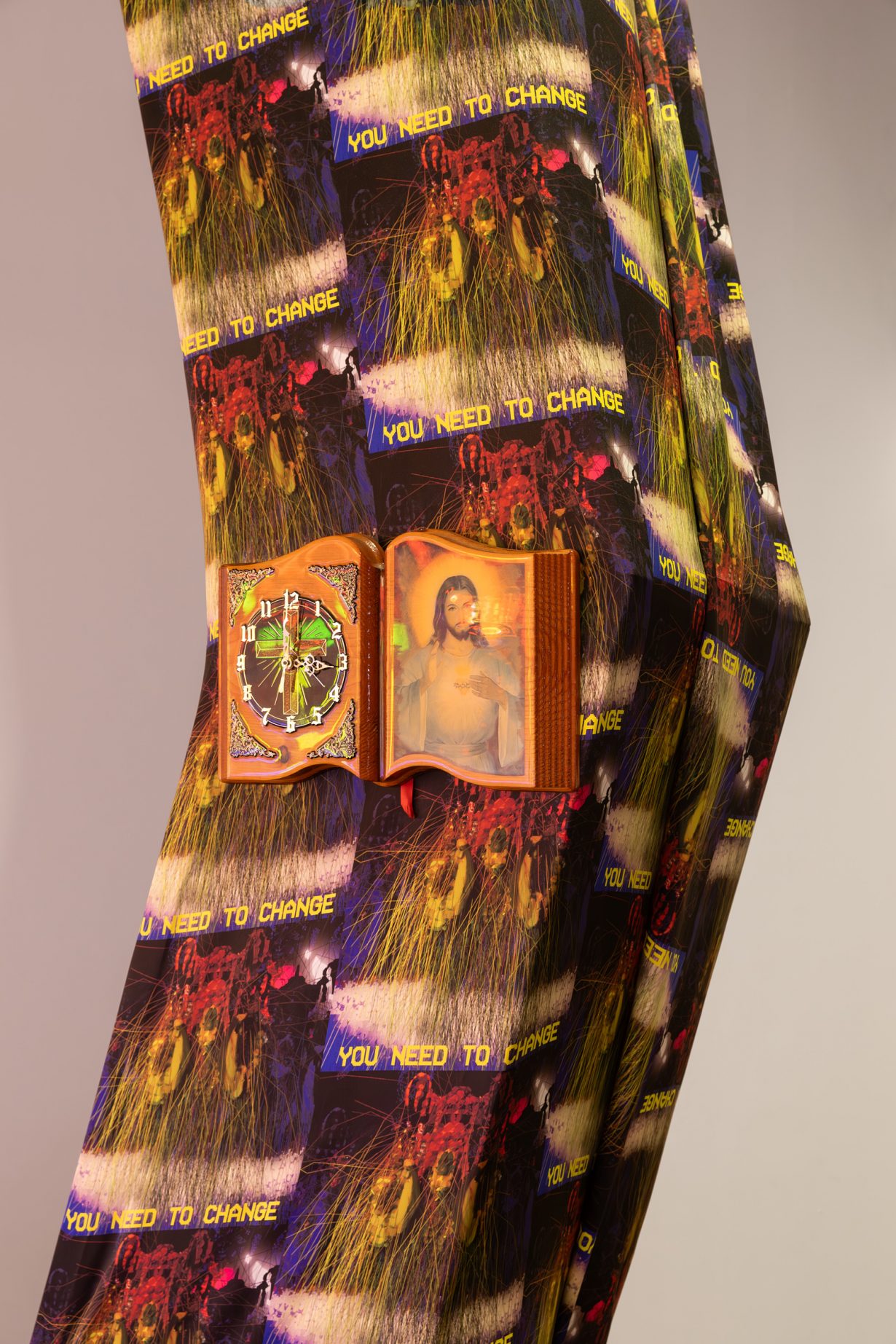

Enter the darkness. There, treelike pillars are studded with crucifixes and decorated in fabrics depicting videogame graphics. Red text is emblazoned across a back wall, mimicking script on a computer screen: ‘This space is for those this country has failed to keep safe… This is a pro-Black, pro-trans space.’ An adjacent television, flanked by two red telephones, supplies instructions for the impending experience, in which visitors are ‘given a chance to be transformed’.

Welcome to The Rebirthing Room (2024), the latest iteration of Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley’s project to archive the Black trans experience using videogame animation, sound, sculpture and performance. The game and surrounding installation expands the artist’s practice of using technology to fuse lived testimony and fictional narrative. The game itself is operated by a controller (dubbed an ‘anchor’) fixed to the floor in the centre of the room. The controller resembles a hooded figure holding rosary beads, becoming a kind of proxy for the player within the game’s first-person perspective. Positioned behind the figure, with hands on each side of the attached controls, the player is then guided through a projection-mapped environment beamed upon three screens that wrap around the gallery walls, each ‘level’ determined by the player’s choices. The result is an experience that, as a whole, falls somewhere between personal quest and collective ritual.

The Rebirthing Room allows the player to choose from six demons that they will attempt to conquer: anxiety, self-doubt, fear of failure, intolerance, addiction and low self-esteem. The images that pulse onscreen are saturated and blocky, echoing the graphics of 1990s RPGs. We hear sad drones and vocoders. After I selected ‘self-doubt’, script ticker-taped across the screen, narrating a voice of internal judgement ‘that tells you you’re nothing, you’re useless, you’re disappointing’. In order to help the audience putatively defeat their worst nightmares, the game’s narrative replays various pre-scripted scenarios of ‘trauma’ (‘Inside you is a MONSTER’ appears onscreen in bold red letters) – leaving the player little room but to submit.

The mission: using the buttons, players must train a searchlight on a series of swarming demons. If you ‘win’, you’re given a self-transformational homily. Lose – as I did – and ‘the monster climbs back into your body’, the narration tells us, feeding on ‘your negative perception of yourself’. A final, damning injunction lingers in blood red letters: ‘Come back when you want to deal with it’. These journeys both puncture the fantasy of videogaming as a zone of autonomous play (these ‘individual’ choices remain hard-coded, part of the game’s rigid inbuilt logic) and underline an intriguing tension throughout The Rebirthing Room: in order to elude one set of presuppositions about identity, the game nonetheless enforces its own.

The force of Brathwaite-Shirley’s audiovisual world is incarnated through a push–pull aesthetic: images that are both hypnotic and minatory, with a directness of address that can feel like a hair-raising therapy session. Strange forms of beauty bloom and pullulate across the game’s interface: microbelike neon spores; banks of crackling static like those emitted by an old TV; scorched-earth palm-fronds inside a digital Heart of Darkness (1899), in which society’s colonising outside forces are vividly manifested within.

If a game controller or VR headset operates as an extension of ourselves, a kind of prosthetic body, then the question follows: do we invent technology, or does technology invent us? Indeed, there are moments when the game closes the gap between artifice and reality. Frequently, these simulations jar and glitch to reproduce a kind of physical sensation within the player, mirroring what’s dramatised within the game: a shudder, perhaps, or a brief, pinching moment of panic or confusion. Yet, though the game promises ‘rebirth’, its fixed limits – how else could these demons manifest, and in what other ways could they be defeated by the player? – define the audience as ‘played’ as much as ‘player’. For example, consider the ‘success’ message received after vanquishing ‘addiction’: ‘You need to wake the fuck up… Fix your own problems. Admit the cravings.’ Talk about a hollow victory.

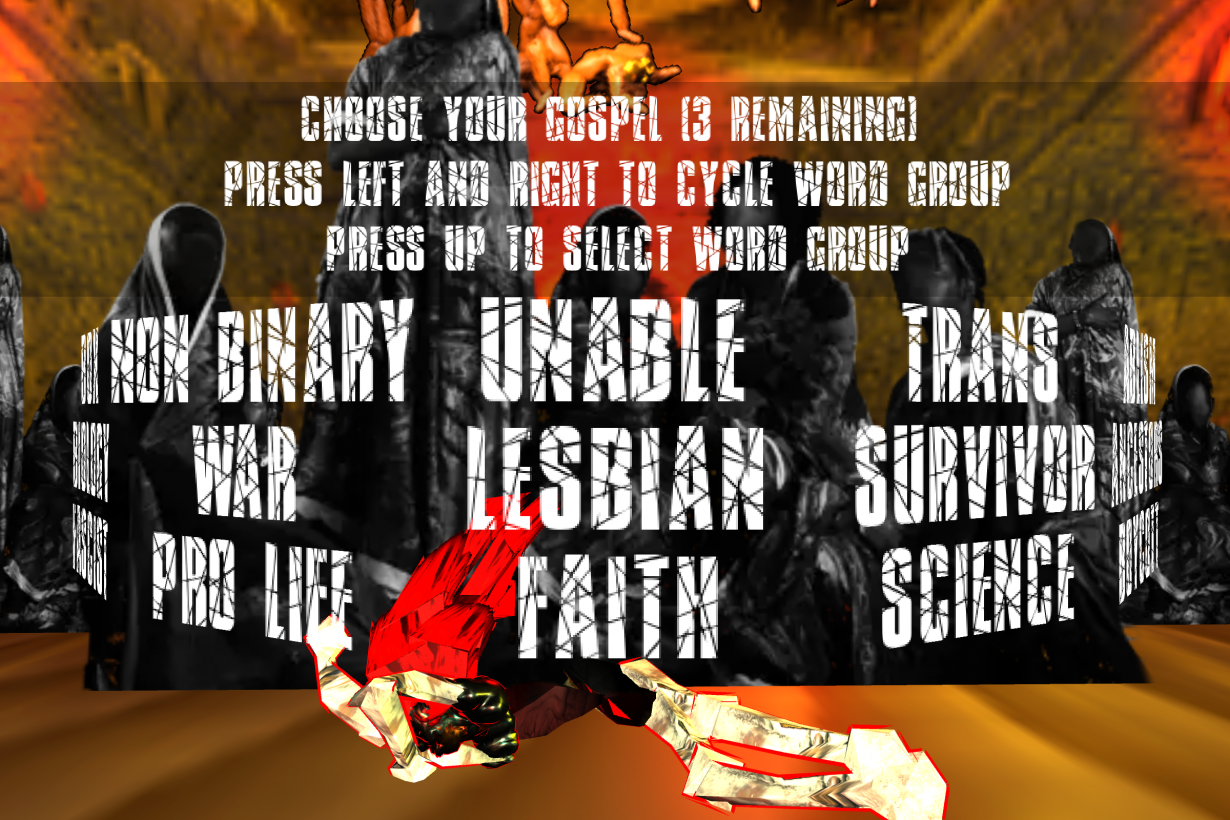

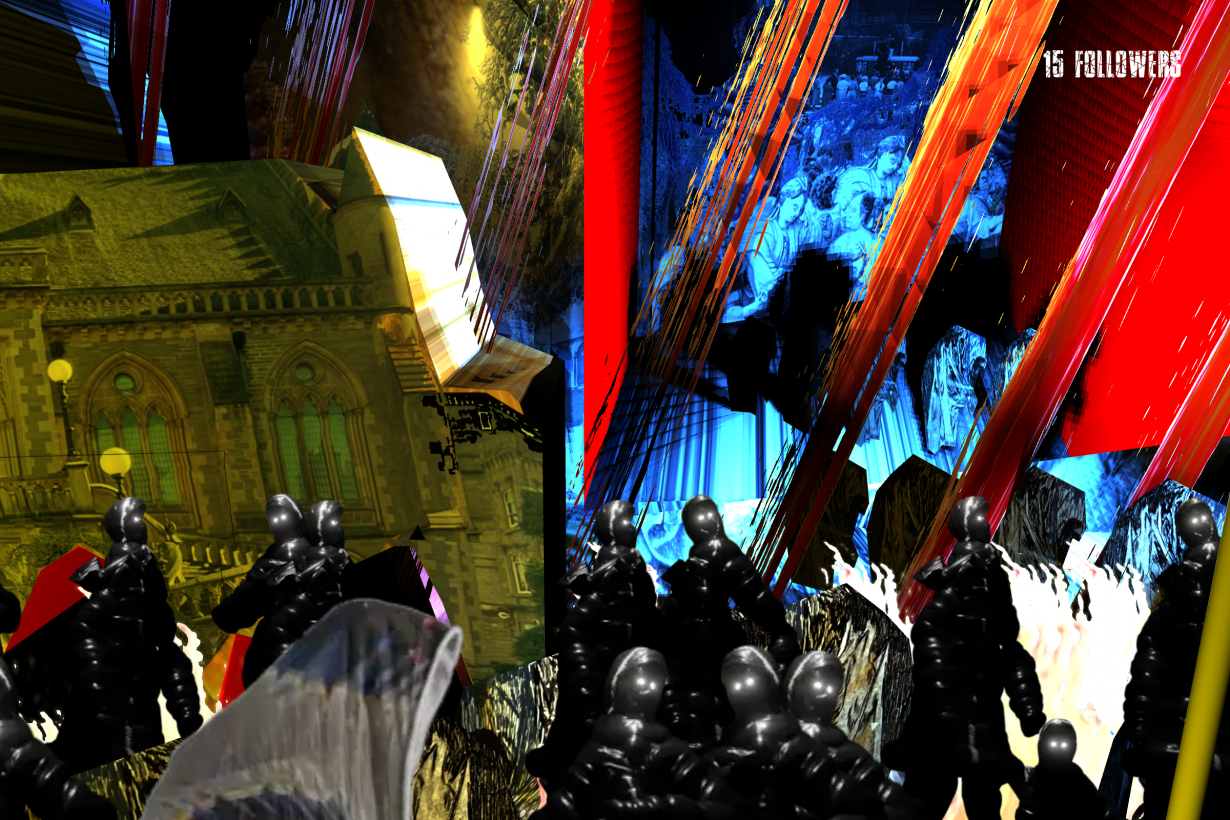

The Rebirthing Room develops one of the recurring themes of Brathwaite-Shirley’s work: how the digital is no longer separate from reality, but embedded within it. The interactive games available on Brathwaite-Shirley’s own website explore this blurring of textures between IRL and online. In Blacktransrevolution.com (2023) the player must choose a ‘new gospel’ for the revolution. Contradictory, jarring categories populate the screen: ‘Non- binary/War/Pro life’, ‘Unable/Lesbian/Faith’, ‘Ableism/Ancestors/Boycott’. Clicking the cursor in time with the prompts, you must gather followers and ‘reassert your position as leader’. The interface is buffeted as if by actual physical blows, recalling the beat-’em-up style of Tekken (1994–). There’s the ambience of a horror film: gaping fangs and washes of blood-red.

Blacktransarchive.com (2020) adopts a similarly bold strategy. It flips heteronormative assumptions about gender identity, posing a more troubling question directly to the player: who do you think you are? The artist has commented that they “don’t like passive artworks”, preferring instead to make the audience “feel a bit responsible for what they see”. The player is made to confirm their own identity: whether they’re Black trans or cis. At the beginning of the game, we’re told that it exists to “store and centre Black trans people”. The imagery that cascades across the interface is fantastical, elaborate: stars shrinking and malfunctioning over corallike digital fragments.

The terms of this virtual realm are clear: “You must agree to centre Black trans people and use your privileges to help them. This is not a place where we make you feel better!” The kind of ‘trans panic’ whipped up by tabloids and populist politicians is turned on its head: “Danger: a cis person has entered the environment”. Warnings flash up against ‘transtourism’; additional security is announced to protect the game’s virtual residents. “Please let me be”: a melancholic, autotuned voice pleads. It’s here that Brathwaite-Shirley cleverly manipulates virtual reality – creating a world that feels ‘real’ and may be based on actual experience, but remains a product of the artist’s imagination – in order to hold a mirror up to the audience’s ethical boundaries. Engaging with Blacktransarchive.com, you’re left wondering about whether it is better to be coerced into doing the right thing, or to remain instinctively free to do wrong. And most crucially, what does either choice say about you?

The power – and failure – of language to define the self is a motif of Brathwaite-Shirley’s output. In Get Home Safe (2022), an immersive installation shown at David Kordansky Gallery in Los Angeles in 2022, the artist explored how numbers and letters could be used to ‘capture and store Black trans information’. Using ASCII code, Brathwaite-Shirley created a kind of haptic record of their navigating the world in a Black trans body, based around the fear of being attacked when walking home at night. The show created an immersive environment of screens, sounds and surfaces, including holograms – based on the movements of three different Black trans people – translated onto 3D-animated characters and then transcribed into the characters and numbers of ASCII text. These were used to create portraits of gender-nonconforming pioneers, such as activist Marsha P. Johnson; Mary Jones, New York’s first recorded transgender person; and writer Janet Mock. In Brathwaite-Shirley’s work, words take on the symbolic work of representation, while also constantly glitching and failing, full of misspellings, halting audio and broken speech. In The Rebirthing Room, the solecism ‘familier’ flares onscreen, blending ‘family’ into ‘outlier’: a painful Freudian slip. Language starts to seem less a system of sense-making than a net that’s permanently being slipped.

In constructing a trans genealogy, Brathwaite-Shirley inevitably shines a light on its erasures from the official record. In The Rebirthing Room, we see redacted portraits of Black trans people, their features blocked out like those of victims or witnesses in crime reconstruction videos. The notion of what it means to ‘cross’ – passing from shame to self-validation, secrecy to acceptance – agitates and buzzes through the artist’s work.

At the Helsinki Biennial last year, I encountered some of their sculptures as part of an installation on the island of Vallisaari. In Thou Shall Not Assume (2023), a series of humanlike figures with cloth-bound heads and elongated bodies were scattered across five different locations: some in pairs or threes, others standing on piles of logs as if ready for a sacrificial pyre. QR codes allowed viewers to listen to the stories of these characters online: their pilgrimage to ‘pass from one way of living to another’ in order to ‘begin life anew’. Fantasy becomes a political tool: a means of ‘acting out’ and inhabiting potential other selves, other lives, forcing us to question the received wisdom about what is natural.

Taken to its logical extreme, Brathwaite-Shirley’s work disturbs the very concept of that prized unit of neoliberalism: the ‘individual’. In the realm of online gameplay, questions of agency and subjection, predetermination and freedom, are constantly negotiated and enacted. How can we be sure if a desire is ever our own? Do we really know ourselves as much as we care to believe? Finally, playing our chosen but carefully coded roles – in life as in virtual reality – the concept of fixed identity itself becomes blurry. In one sense or another, we’re all in transition. Come back when you want to deal with it.

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley’s The Rebirthing Room is on view at Studio Voltaire, London, through 28 April