In his latest film The Shrouds, characters can livestream their loved ones rotting in the grave. Is this a new monumentalism?

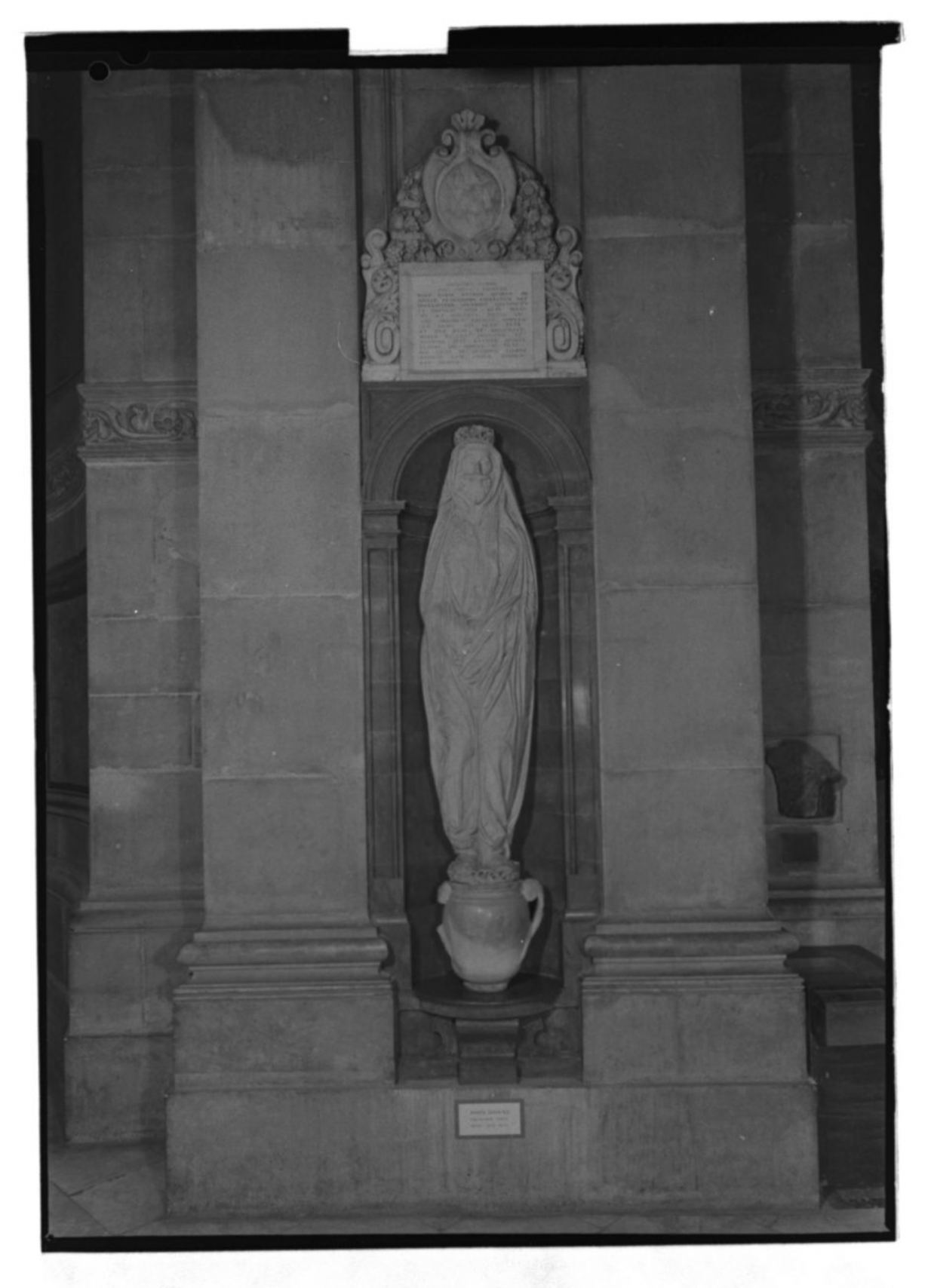

In 1631 the metaphysical poet John Donne raised himself from his sickbed, wrapped himself in a winding sheet and posed, as if already dead, for a memorial that would later decorate his grave. The resulting statue, now housed in St Paul’s Cathedral, shows Donne, bearded and serene, the ghost of a smile playing about his lips and the winding sheet knotted above his head like a crown. Such resurrection monuments were popular in the seventeenth century; their creation and display a ritual that allowed both their subject and their audience to contemplate death before the grave.

In David Cronenberg’s latest feature film, The Shrouds, these monuments and the winding sheets themselves are updated for the contemporary world. In a near future, businessman Karsh (Vincent Cassel) is the inventor of ShroudCam, a flexible sheet of cameras that wraps around a corpse to capture a real-time image of the decaying body that is then displayed on the gravestone. In one scene, Karsh, evoking Donne, tries on his own invention while still alive. He shuffles awkwardly into one of his shrouds, which resemble giant metallic pupae, and stands mute and imbecilic in his bedroom. A computer shows the skin and flesh being digitally peeled from his body to reveal the skeleton beneath. As Karsh says: “I wanted to know what it felt like to be wrapped, to be shrouded.”

Karsh invents ShroudCam and a supporting business, GraveTech, after the death of his wife Becca (Diane Kruger). In one of the film’s first scenes, the widowed Karsh is on a blind date in a restaurant overlooking his GraveTech cemeteries and explains his motivation to his luckless companion. “When they lowered my dead wife into the ground I had an intense, visceral urge to get into the box with her. I couldn’t stand that she was alone in there,” he says. He takes her to Becca’s grave and shows her an image of the skeleton, the flesh rotted after Becca’s death from cancer four years earlier. He explains that with recent updates he can now rotate the cameras and zoom in, showing the fine detail of her skeleton in 4K. “I can see what’s happening to her,” he says. “I’m in the grave with her. I’m involved with her body the way I was in life only even more. And it makes me happy.” The date retreats in shock while Karsh, oblivious to her discomfort, suddenly notices something in the image: nodules growing on Becca’s bones that had not been there before.

The origin, purpose and reality of these nodules is one of the central mysteries in The Shrouds. The other is an act of vandalism targeting the cemetery containing Becca’s grave. GraveTech’s digital resurrection monuments are smashed and the fibre optic cables that capture their images of decay are tampered with. Who’s responsible? Is it the Chinese, the Russians, Icelandic ecoterrorists? And what do they want? Conspiracy theories abound, involving necrotic surveillance networks and illegal medical experiments, but no conclusions are ever reached and these narratives prove to be of secondary importance.

The film’s action is instead carried by conversations between its small central cast – composed of Karsh, Becca’s twin sister, Terry (also played by Kruger), Terry’s ex-husband Maury (Guy Pearce) and Karsh’s AI assistant Hunny (voiced by Kruger in sultry tones). Kruger also appears as Becca herself in a series of scenes that could be flashbacks, dreams or hallucinations (it’s never clear). In each scene, Becca and Karsh lie naked in bed as Becca’s cancer progresses. She wears a medical collar around her neck that summons her to a mysterious oncologist, Dr Eckler, who never appears in the flesh and, we learn later in the film, also happens to be Becca’s first sexual partner. As Becca is summoned, naked each time, Eckler claims more of her body parts. He amputates a breast, then an arm, and perhaps a leg, returning her to Karsh with scars and stitches that Cronenberg never flinches from displaying. As the illness progresses, Becca and Karsh can no longer have sex and when they try, he breaks her hip. It’s the film’s most gruesome scene, and shocks by sound alone. “Are you asleep? Am I still alive?” asks Karsh at one point. “I don’t know,” says Becca, and kisses him.

It’s possible to see The Shrouds as a discussion of resurrection in the digital age. In real life, the nascent ‘grieftech’ industry offers a number of services that promise to restore the dead, from chatbots trained on a loved one’s emails and texts to interactive 3D avatars reconstructed from photos and videos. The Shrouds briefly plays with the implications of this technology, with one character worrying that the vandals who attacked GraveTech might hold the images of the dead to ransom, like hackers stealing hospital records. It’s a reminder that if we choose to enshrine our grief within technology, it becomes subject to the same manipulations and perils as the rest of the digital world. It removes us from the object. The fidelity of the ShroudCam images is also presented with some ambiguity in the film, particularly the strange nodules on Becca’s skeleton. In several scenes, characters suggest digging up graves to examine remains, but each time the idea is shot down. Despite the supposed intensity of these digital images, they are still easier to bear than the thing itself.

The film is only ostensibly concerned with these lines of inquiry, though, and in reality the questions it poses are much older. Cronenberg wrote The Shrouds following the death of his wife Carolyn in 2017 following 43 years of marriage. The director told the Los Angeles Times that he ‘read all the grief books and none of them matched exactly my grief’. They were too intellectual and too abstract, he says; they didn’t mention sex. ‘And I thought, well, that’s not the way I feel. For me, it’s really physical. Really physical, along with everything else.’ This is the film’s ultimate concern: the location of love. Is it something to be found in the body or the spirit? Does love die with its subject, or linger in the living? The digital instantiation of Karsh’s grief, including the images produced by ShroudCam, are not redundant here, but instead represent the lengths one might go to capture the object of one’s love through other media. Anything to avoid losing contact, even watching a corpse become wormfood.

Cronenberg approaches this theme through the duplication of Becca. She appears in flashbacks but also in the present; in physical form as identical twin Terry, and as the voice of AI assistant Hunny, who is herself protean, shifting appearance to entertain and horrify Karsh. At one point, Karsh and Terry have sex, mirroring the bodily positions of Karsh and Becca at the time when Becca’s hip was broken. “Do I remind you of Becca?” asks Terry. “Do I make the same sounds?” The treatment of Becca’s illness also summons the question of love’s habitation. If such a feeling is rooted in the physical body, can it be sliced away, piece by piece, by amputation? Is it, too, eaten by disease? The unseen Dr Eckler keeps Becca’s body parts for unknown purposes and Karsh proclaims himself jealous of this theft. “I lived in Becca’s body. It was the only place I really lived,” he says. “Her body was the world. The meaning and purpose of the world.”

Karsh’s identification of Becca’s body with ‘the world’ means her death can never fully be accepted, as what can survive without a world to inhabit? Such explorations are not subtle – Cronenberg rarely is – but capture the malign transformation of grief. In classic Freudianism, mourning turned inward becomes melancholia; a pathology in which the mourner grieves a loss of meaning in their own ego rather than in the external world. The repetition of Becca’s image throughout the film, in body and voice, conveys the claustrophobia of this grief. Wherever Karsh turns for comfort he is confronted by the source of his anguish; by shades of a love that can never be laid to rest and instead rots under his obsessive gaze. In the film’s final scene, he boards an airplane with a new lover, only for the woman to manifest Becca’s scars and speak in her voice. At this point, Karsh’s melancholia has consumed his reality completely, subjugating not just the digital realm but the world of the living, too. In response to the woman’s transformation he says nothing – and leans in for a kiss.

Needless to say, there are healthier ways to understand the interdependence of body and spirit in the experience of love. Donne himself made the subject one of his central themes, and in his poem ‘The Ecstasy’ describes a pair of lovers lying hand in hand on the bank of a river. His language probes the hazards of such physical intimacy. The lovers are not just held by one another but ‘firmly cemented’, ‘intergraft’; their shared gaze is ‘twisted’ and their love so totalising that their bodies are already prepared for the grave, immobilised ‘like sepulchral statues’. But such perils are necessary, and Donne concludes that even if love is transcendent it does not spring from the air. It requires a material basis; it is something that is founded and conveyed through the hands and the eyes. And just because all bodies must one day rot in their winding sheets does not mean we should look away. Perhaps, as in The Shrouds, we’ve little choice but to look closer.

James Vincent is a writer and journalist living in London. He is the author of Beyond Measure (2022), a history of the concept of measurement.