The photographs in Strange Instrument at Pace Gallery, New York, demonstrate the intensity of a deliberate eye recording life over a period of three decades

Two photographs embody the little oddities that characterise Strange Instrument, an exhibition of 45 works by the late South African photographer David Goldblatt. Consider the first: a hand peeking out of a blanketed body at a trading store. The date is 1975. The place is Hlobani, in Transkei, in the southeast of his country. Imagine David Goldblatt the photographer, in the market, searching for an image. He sees a man covered by a blanket. What he finds immediately strange is not the blanketed body inside a store, but the folds around the man’s palm, how his fingers catch the light.

The second, George and Sarah Manyane, 3153 Emdeni Extension, from August 1972, is two images rolled into one: a woman on the left, folded onto a chair barely containing her frame, and a man on the right, standing at a doorpost, his turtleneck bulging from beneath his suit like a bandage around his neck. The woman, far in the background, is as immense as the man in the foreground. What is the white material spread in front of her feet? And the man – why is his last button undone? Both figures have their arms in similar positions, but they share something else – a slight bend in their postures, as if the rotation of Earth itself was causing them to sway.

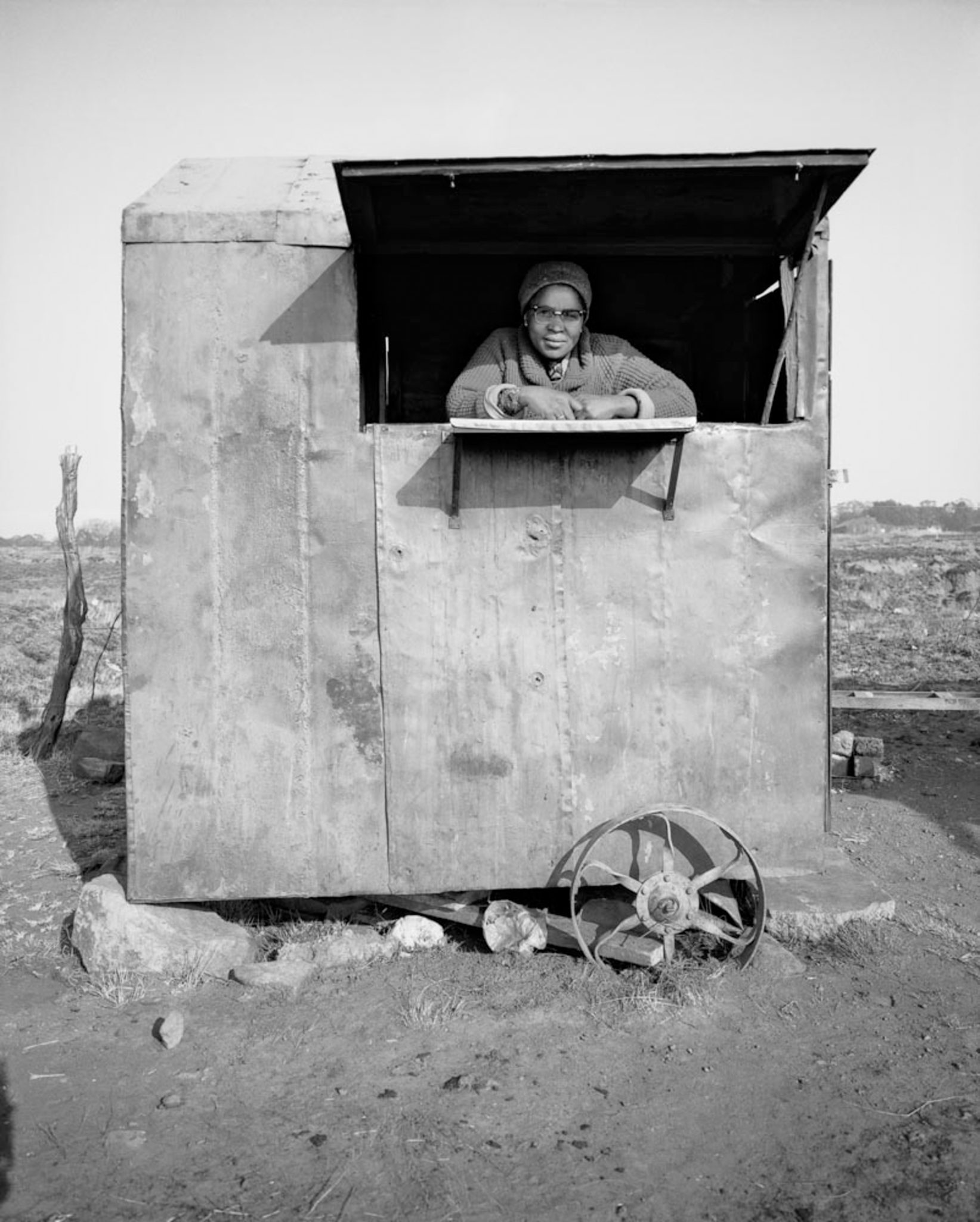

The photographs in Strange Instrument demonstrate the intensity of a deliberate eye recording life over a period of three decades. The earliest work in the show is from 1962 and the latest is from 1990 – the same year the antiapartheid fighter Nelson Mandela was released from prison. Zanele Muholi, one of Africa’s most famous living photographers, must have been thinking about Goldblatt’s way of seeing while curating the show. Muholi and Goldblatt had a close relationship after meeting at Market Photo Workshop, a contemporary photography community in Johannesburg cofounded by Goldblatt. He became their mentor, and in turn they came to learn a lot from him. One understands Muholi’s choices for the show better with this information, since the photographs are mostly taken between the 1970s and 80s, covering the period of their childhood. Muholi’s influence is also felt in how they organised the photographs into 22 categories with titles like ‘On Nurturing’, ‘On Textured’, ‘On Poverty’, placed alongside Goldblatt’s original captions, which are mostly descriptive.

In an Art21 interview aired a few months after he died, in 2018, Goldblatt declared: “The camera is a strange instrument. It demands, first of all, that you see coherently.” But what kind of coherence did Goldblatt attempt to articulate?

Although he resisted describing himself as an activist or his work as being political – a luxury no Black artist in the country at the time would have been able to afford – Goldblatt, born in Gauteng Province in 1930, did most of his work in apartheid South Africa. His grandparents had arrived in the country from Lithuania during the late 1890s after fleeing persecution aimed at Jews, so he himself belonged to a lineage of the oppressed. A fear of Afrikaners was instilled in him during the Second World War, when the pro-German, anti-Jewish Afrikaner group Ossewabrandwag was active. Yet for him what seemed most important was first to exist simply as an artist accurately documenting the times.

The works in the show cut through private and public life, enumerating the joy and sadness of the cities, streets, rooms, offices, parks and landscape. Muholi must be aware of the incredible access Goldblatt – because he was a white South African – had to these spaces, but that in itself raises the question of whether or not Goldblatt himself thought about it. In the Art21 interview, Goldblatt gives hints as to his understanding of racial tensions not only as a South African but also as an artist looking at it critically. Publishers would look at his images, photographs of white and Black people in sometimes intimate positions, and ask, ‘But where is the apartheid?’ “To me it was embedded deep in the grain of those photographs,” he said.

In one of the most striking pictures in the show, a Black girl sucking her thumb stands behind a white man, both of them with contemplative eyes, looking at the camera. Without the tension that pervades the image, they could be mistaken for father and child. But the tension is the crux of the photograph: more fascinating than the operations of the camera as an instrument are the associations it makes possible.

David Goldblatt, Strange Instrument was on view at Pace Gallery, New York, 26 February – 27 March 2021