Is the artist’s London Underground redesign rebellious expression or aristocratic contempt?

What is it like to be David Hockney? Hockney, obviously, is someone very famous and successful: “Britain’s greatest living artist,” people will sometimes tell you. Those bright, sunny, watery California paintings of the late 60s and 70s are firmly installed as a fixture in our collective cultural unconsciousness: parodied in such diverse entertainment properties as Bojack Horseman and Hey Duggee.

But still more than that: this is a man who, in 1972, made a painting (one of those big, sunny California things, of course) that a few years ago, while he was still alive (of course, as he remains alive even now), sold at auction for over $90 million. Sometimes I think it’s easy to take these sort of dementedly inflated top-end artworld bullshit prices for granted: just the sort of thing that, you know, happens, for some irrational reason us mere unmoneyed mortals will never understand. But then I think: imagine if you’d made something, that sold for that kind of money? I appreciate that the artist is unlikely to profit from the transaction directly – but what I’m getting at here isn’t really about that. You’ve made this thing, right? However many years ago. It took you, let’s say, a few months. Off and on. And now it’s worth… more money than anyone could ever possibly need, in their lifetime. Isn’t that obscene?

I think, if this sort of thing happened to me, then it would cause me to seriously question the foundations of the world on whose ground I had previously believed myself to walk. This happening to me would completely sever any assumption I had previously held, that the value of anything is determined by how much time, work, effort (call it what you like) went into it. It would make me feel like a sort of god – but not in a good way, kind of like I’m a god who’s being tricked. Everything would start to feel like it was unfolding in a sort of hazy, enchanted dreamworld (quite like, in fact, Hockney’s radiantly static California), where I had been trapped forever, in a sort of terrible bliss. Maybe this is a psychologically quirky reaction (or, imagined reaction), and most people would just sort of go: “huh. 90 million dollars. Sounds about right! Looks like I’m finally getting the credit I deserve!” But I don’t know. If this happened to me, it would feel like a horrible joke. Nothing I ever did again would feel like it mattered.

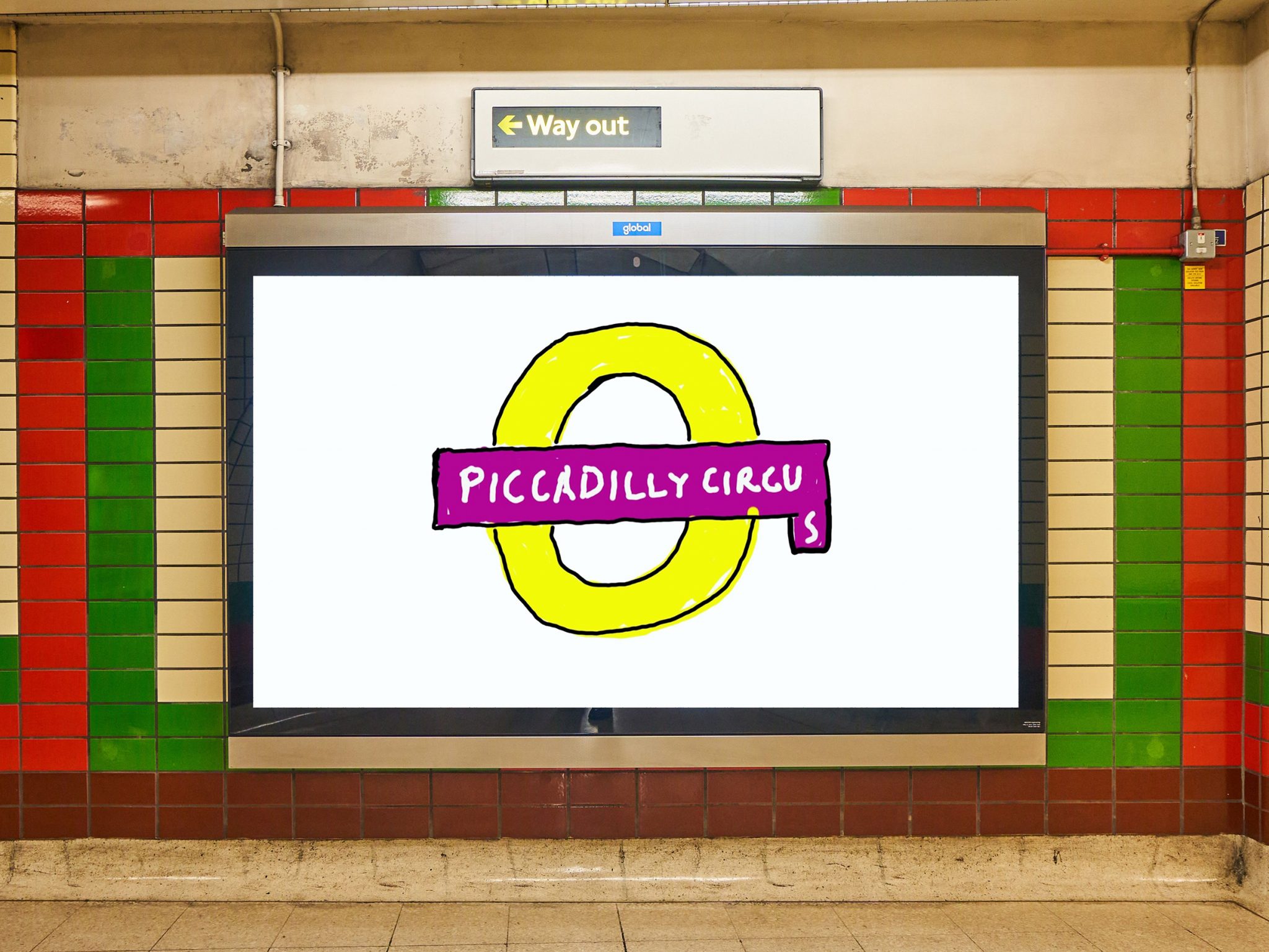

Perhaps we should read Hockney’s recent work as expressive of this sort of disillusionment with external reality. Certainly, over the course of the past few years, as Hockney’s other work has been carted round from huge blockbuster exhibition to huge blockbuster exhibition, a steady pattern has been emerging. Every now and then, some high-profile institution will commission Hockney to do some special logo for them or something – and then Hockney will send them something obviously completely tossed-off, that looks like it was done on MS Paint (though was in fact done on his iPad), and everyone who’s interested in art will post about it and make themselves Pissed Off. This happened in 2017, when Hockney did a special one-off masthead for The Sun newspaper. It happened last year, when Hockney did a clownishly lazy cover for the New Yorker. And it happened last week, when Hockney provided the London Underground with a new logo for Piccadilly Circus which resembles nothing so much as the tube map version of the original concept art for Krusty from ‘The Simpsons 138th Episode Spectacular’. The last one is particularly funny, as Hockney doesn’t even seem to have bothered trying to make the purple box where the text was meant to go the right size.

And in a way, this is brilliant: in a world where everyone is expected to maintain a very positive affective orientation to their jobs, where to be employable means to be able to pretend that all the niggling bullshit your superiors are likely to subject you to is in fact a crucial element of your ‘passion’, Hockney’s open and apparently uncaring rejection of this principle does what perhaps all great art ought to. It shows us a different way of seeing – and with that, the possibility of a different way of living. Imagine seeing Hockney’s Piccadilly Circus logo, on your way to work on the tube. No need to kill yourself with the effort, it says to you. Do the bare minimum to scrape through.

But of course: the problem with this way of seeing things, is that it might not quite work out for you, if you’re not as established in your profession as David Hockney. The simple truth is that almost no-one else would be able to get away with designing, say, a logo for a tube station, that looked like this. Hockney’s laziness is enabled by his material position – as someone who at some point made a painting that someone was willing to pay over $90 million for.

With this in mind, it seems perhaps more natural to read Hockney’s rubbish late-period corporate logos and so forth not as an open expression of the rebellion of the idle, but as an arrogant gesture of aristocratic contempt: a privilege the artist possesses, but cannot justify. This isn’t true of the New Yorker cover, and certainly not The Sun masthead (probably no-one should be agreeing to design things for The Sun – but equally it seems fine to me to rinse them for all they’ve got). But in the case of the London Underground logo, Hockney was paid real public money, ostensibly to make something to beautify public space – and he gave us this instead. There is something glorious about his cynicism, yes, but there is also something nasty about it (it’s funny, too – but plenty of things are funny and nasty at the same time).

I can do this, Hockney’s Piccadilly Circus logo seems to tell us. I can get away with it, but you couldn’t. That’s just how things are.