American People at the New Museum reveals the structures of power that underlie the mundane

It has become commonplace to state that the battles fought by American artists of the late 1960s and 70s against institutionalised racism and misogyny are depressingly relevant today. Yet the first rooms of Faith Ringgold’s timely retrospective at the New Museum suggest an illuminating difference between her own protests against institutional power – as delivered through six decades of paintings, textiles, sculptures and performances – and those of a new generation who would dismantle it.

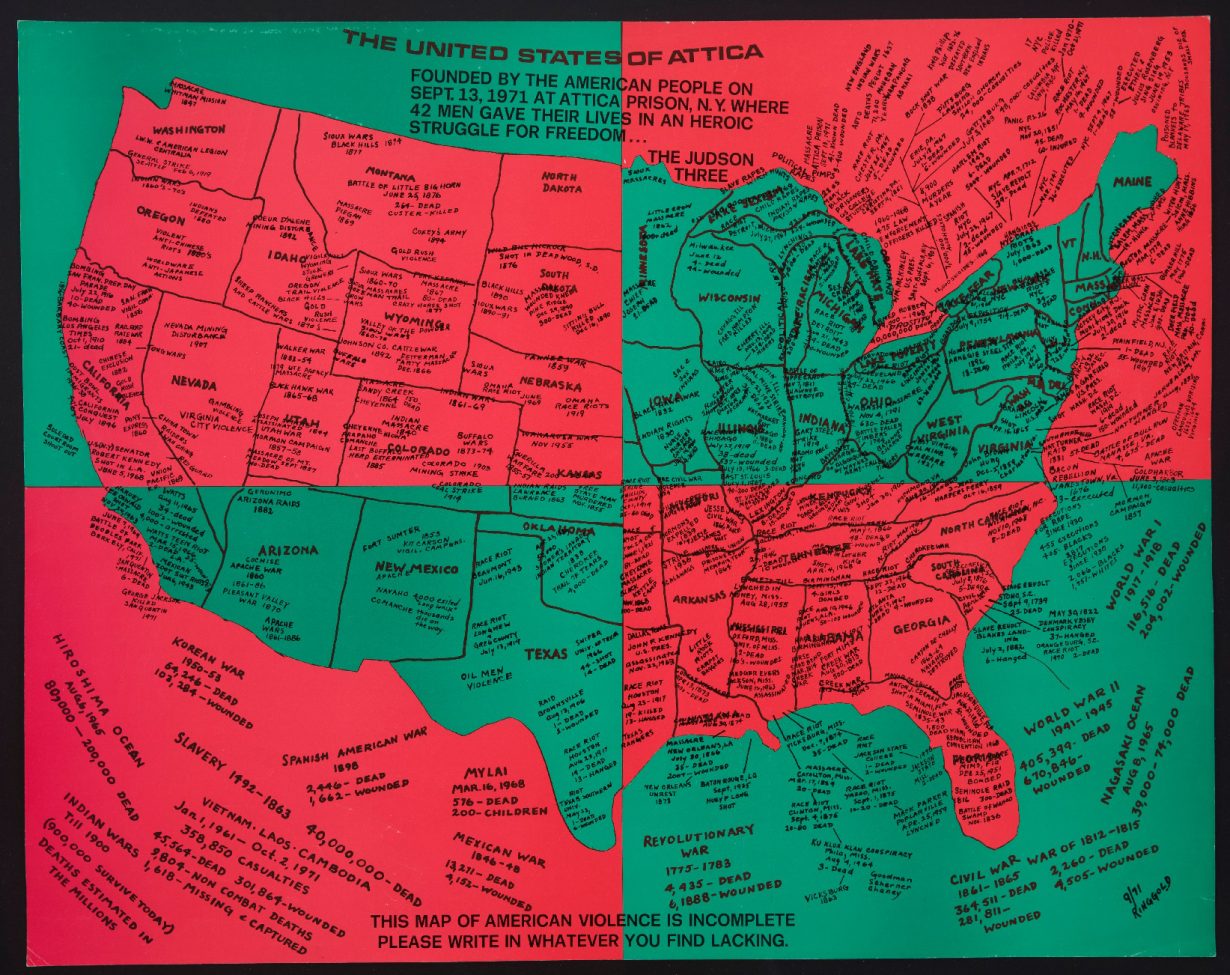

Take the acrylic-and-graphite-on-paper Freedom of Speech (1990), in which the stripes of the US flag are replaced by the opening sentence of the First Amendment and its stars overlaid by the names of those (ranging from Dred Scott to the KKK) whose persecution or toleration offends those stated ideals. The work is one of a series of flag works that followed Ringgold’s conviction, in 1970, for ‘desecrating the American flag’ as a co-organiser of the People’s Flag Show at Judson Memorial Church in New York. Yet Ringgold’s citation of the flag illustrates a faith in its principles that endures beyond any merely symbolic defacement (to put it another way: to adapt the flag to one’s own protest is to avail of the freedoms it is supposed to enshrine). As Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton founded the Black Panthers to enforce the constitution, so Ringgold’s anger seems directed not towards the overthrow of American institutions so much as against their continued abuse.

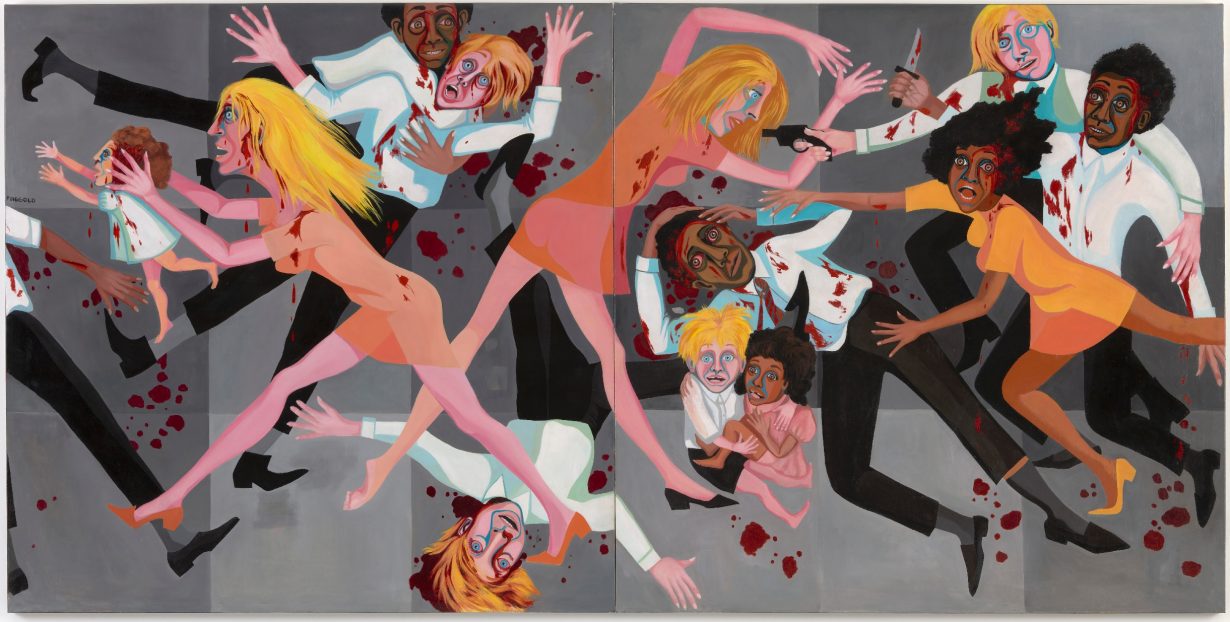

This offers one lens through which to read Ringgold’s prodigious output. Among the most powerful of the early works in this show, for example, is a mural commissioned for a women’s correctional institute (For the Women’s House, 1972). Responding to suggestions from the incarcerated women, the eight quadrants of the square wall depict women working in jobs ranging from policewoman to president. Again, the political thrust of the work is to highlight the injustices that obstruct disadvantaged women in their pursuit of the conventional aspirations of American life. These inequalities are documented and decried by the ‘American People’ series of figurative paintings beginning in 1963. Foregrounding female and Black perspectives on a turbulent society, the series ranges from bluntly satirical portraits – the ninth in the series is titled The American Dream (1964) and depicts a genteel white woman flashing a diamond ring – to more complex commentaries on how power shapes the way we see.

The 2.4m-wide The American People Series #19: US Postage Commemorating the Advent of Black Power (1967) depicts a hundred faces – Black and white – in a design for a postage stamp that might superficially seem to celebrate American diversity. Yet two messages are hidden in the painting’s composition. The first, easily spotted, is the legend ‘BLACK POWER’, which runs on a diagonal across the grid of faces. This might seem at first like a celebratory or defiant stamp, until you look more closely and realise that the thin lines that separate one face from another collectively spell out the disguised phrase ‘WHITE POWER’. Where Minimalism and Pop art claimed to empty art of political content, Ringgold works in the opposite direction: she reveals how even mundane commodities like stamps and the supposedly neutral form of the grid are structured at a deeper level by the realities of power.

This narrative impulse is apparent in everything from the soft sculptures that Ringgold incorporated into didactic performances such as The Wake and Resurrection of the Bicentennial Negro (1976), which drew on the history of West African masquerade, to the painted textiles that give to Black women the central role that the Tibetan and Nepalese scrolls by which they were inspired reserved for Buddhist deities (the polemical Slave Rape series of 1972 being one powerful example). As those examples suggest, Ringgold has claimed for herself the modern artist’s right to draw on diverse cultural traditions in freely expressing her own experience of the world.

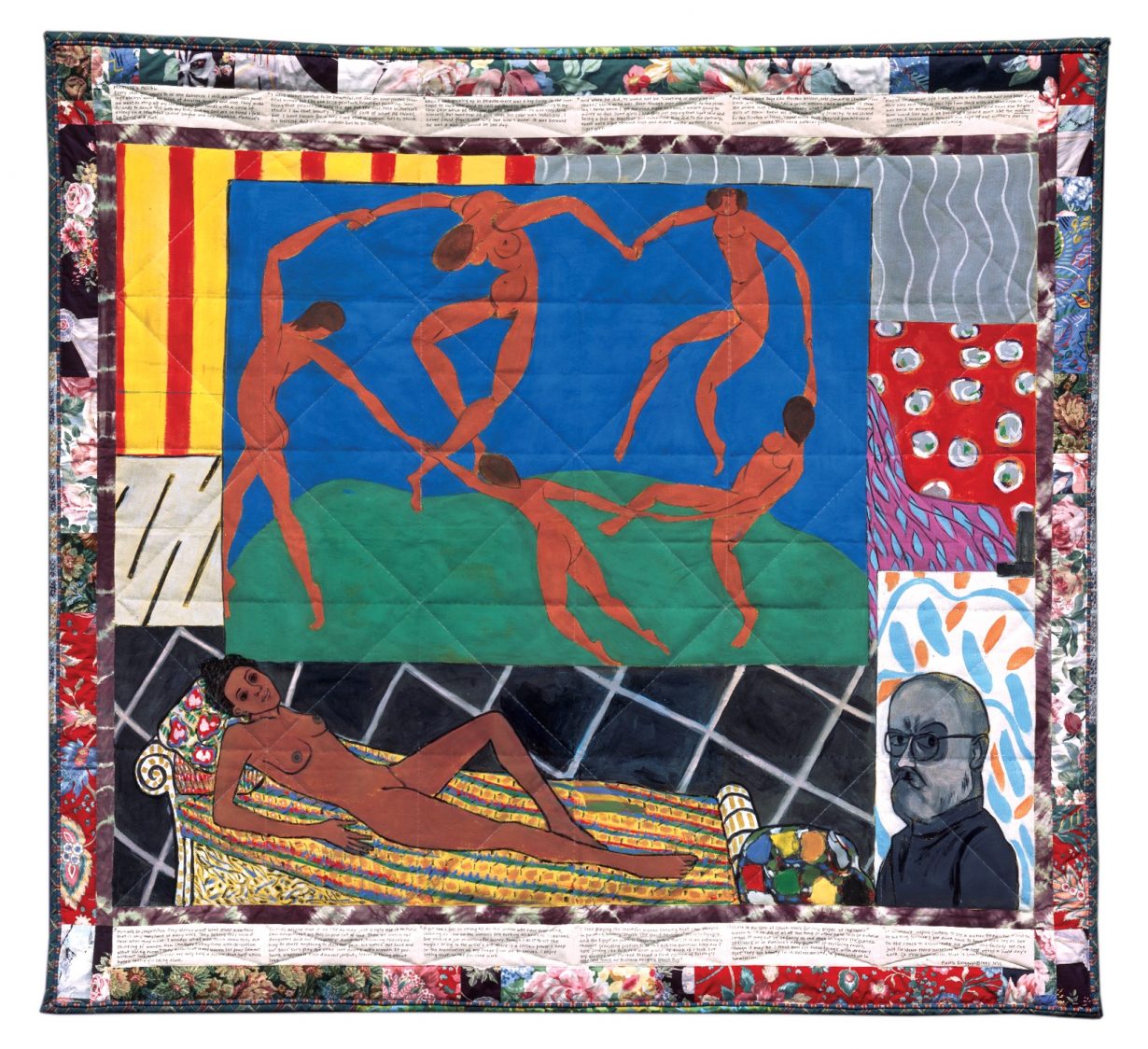

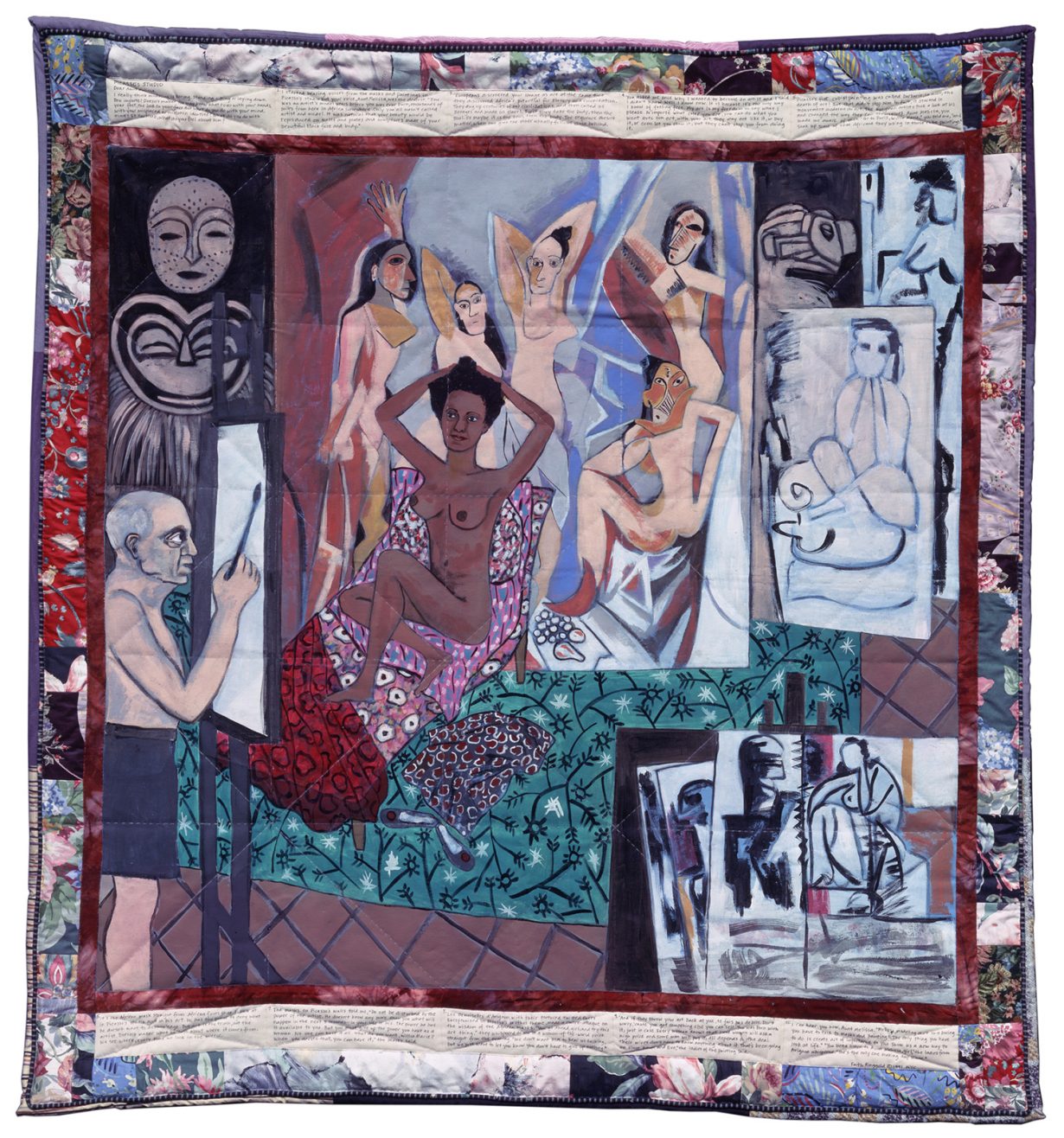

This resolve is apparent in the extraordinary suite of 12 painted quilts, collectively titled The French Collection (1991), that run around the New Museum’s fifth floor. Beginning with the image of four Black women dancing through the Louvre, the series uses words and pictures to tell the fictional story of Ringgold’s alter ego, Willia Marie Simone, as she moves through turn-of-the-century Paris. Black figures are inserted into the foundation myths of modern art, and so we see Joséphine Baker as Manet’s Olympia (served, in an inversion of the original, by a white maid), while another imagines James Baldwin sitting cross-legged at Gertrude Stein’s salon. The suite is both a celebration of the freedoms from which what we call modern Western art emerged and a critique of the failure to extend them beyond privileged white males. In a satisfying art historical loop, Willia can be seen modelling for Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), the painting besides which Ringgold’s own response to Guernica (American People Series #20: Die, 1967) was positioned when MoMA was rehung in 2017. The abiding impression of this survey is that Ringgold’s work does not hasten the dissolution of the modernist canon, but dramatically expands and revitalises it.