“I really love making objects. They’re therapeutic for me. They’re part of the holistic function”

Harry Gould Harvey IV was born and raised, and continues to reside, in Fall River, Massachusetts, the economically depressed postindustrial city where Lizzie Borden axe-murdered her parents. As an exhibiting artist, Harvey is a sculptor and draughtsman; but fundamentally he is a lover of art. Two years ago, with his wife, Brittni Ann, he founded the Fall River Museum of Contemporary Art, a half-sardonic, half-earnest title for an institution he hopes will reinvigorate his hometown.

Now in his early thirties, Harvey worked for several years as a photojournalist, a skill he today uses mostly on Instagram, where he actively aims to cultivate a community beyond New England. My first encounter with Harvey, however, came through seeing his drawings in galleries: esoteric-seeming diagrams with exclamations of artistic devotion: ‘please art! help!’ or ‘art saves!’ or ‘regnant ideas everywhere!’ Some drawings go deeper and hint at a vast, self-aware theology underscoring Harvey’s oeuvre: ‘Attempts at trying to rationalize a preposterous harsh reality with no master nor god!’

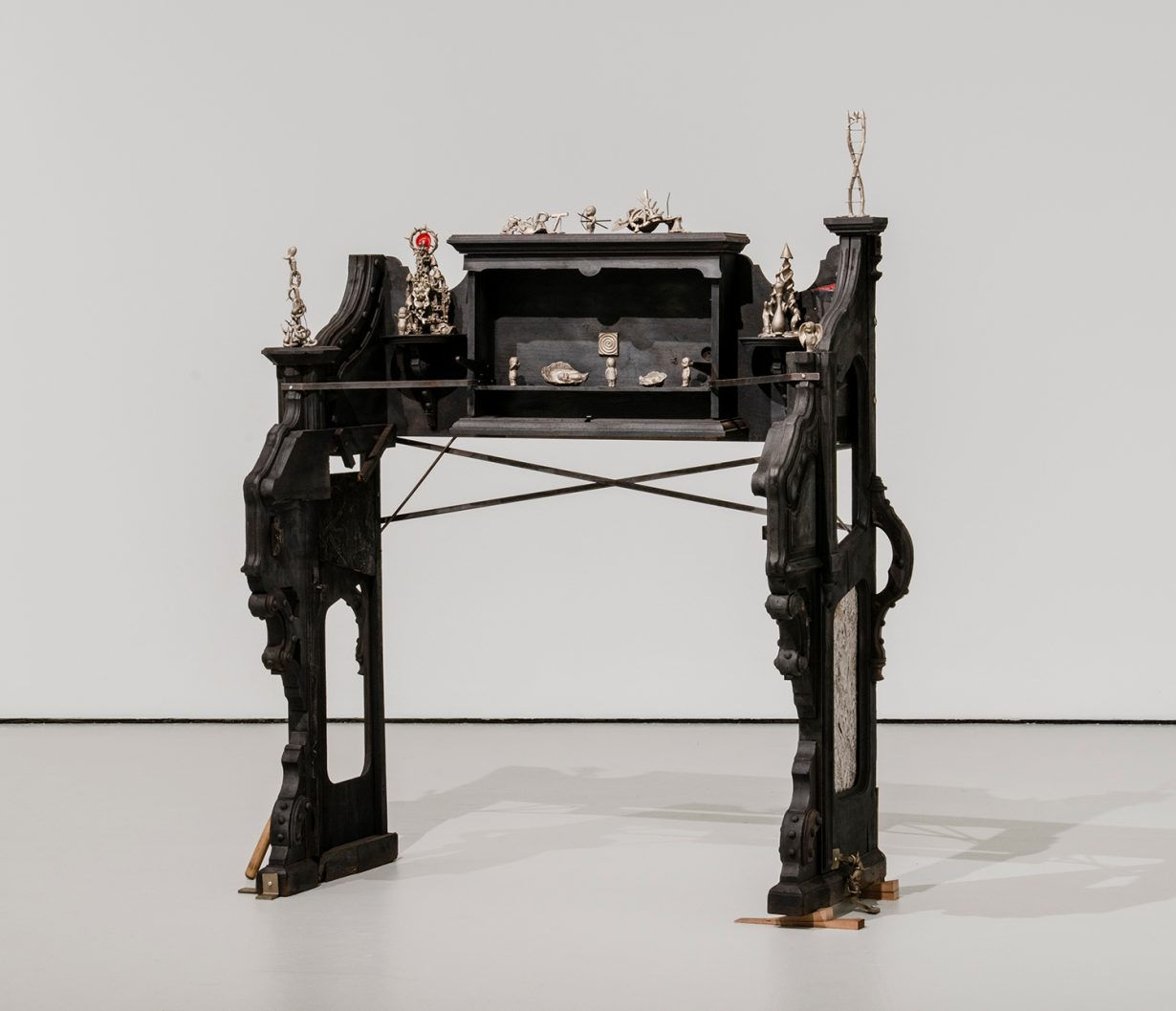

Harvey is a reluctant but engaged Christian. His written drawings ring arch and biblical in tone, and he uses them to reaffirm his path of salvation, prayer and service. Almost all his work relates to sacred architecture: his drawings are framed in elaborate gothic ornamentation, and his sculptures usually take the form of miniature cathedrals.

We spoke over video, with Harvey sitting in the kitchen of his home while I sat in my yard. He later toured me through the rest of the house, including his downstairs workshops, his wife’s studio and a prayer room. He’d owned this house for several years, but the building’s appearance suggested he might be illegally squatting there, with exposed electrical circuitry and a conspicuous absence of drywalling in every room. He seemed to take pride in his raw living environment, and was careful to note that he takes far better care of his museum.

When Harvey speaks, he releases a miasma of meanings, and I often felt myself swimming in his rapid philosophical musings and archaic references. He is a self-directed scholar of history, and his work often invokes time, with wooden ornamentation sourced from burned buildings, candle wax drippings and used industrial heaters. We spoke for over two hours, and afterward he offered to send me some sticklebacks, a Fall River seafood dish.

Harry Gould Harvey So I’m not sure, exactly, what your intentions are with this interview. What do you ask about?

Ross Simonini I like to discuss the life and person around the art, rather than the art itself.

HGH OK. Yeah, I totally know what you’re talking about, because that seems to be my relationship with art. I love it so much, but I have frustrations of course. I think it’s one of the more accurate social sciences that I participate in, where I could convey a greater sense of my personal journey to the collective.

RS What’s your relationship to Christianity?

HGH My relationship to Christianity was one that I entered attempting to negate to the highest degree, because of the patriarchal history, the monarchical nature of the papal supremacy, my distaste growing up in Portuguese Catholic high schools, my distaste at having to say prayers in Portuguese, and what felt like kind of forced indoctrination. So I entered Christianity trying to negate all that. It’s complicated. I feel like some sort of spiritual worker in the real world, but I’m a student of the comparative religions. So it’s not so much that I feel Christianity has a place more than Islam or Judaism or Bahai or Hinduism. But I spent some time in a detention centre as a high school student and read the Bible and it became like a source text for me, allegorically, poetically and linguistically, for my own self-discernment. But I’m interested in faith. I’m not interested in belief.

RS What’s the difference for you?

HGH Belief is a knowing that’s not like a gnosis, that’s not like an internal knowledge. Belief, in my understanding, is the ossification of faith. But faith must be living and refreshable or else you’ll fall victim to the ossification of belief. And then belief becomes a structure that we have to combat with mysticism, which is kind of antithetical to the whole point of having faith to begin with.

RS Do you dislike mysticism?

HGH No, but I’m not interested in esoteric knowledge because I was so satisfied with the exoteric. I have had to dive deeper into the esoteric now, but I hate how alienating it is to the general public. And I hate how dead-in-the-eyes people get the second you start talking about anything that alienates anybody. But I think our modern conception of what it means to be mystical is very different from what I understand it as. I’m not interested in being antithetical to anybody’s belief. And I don’t want to impose any type of political ossification of faith onto anybody’s true knowledge of themselves. Ultimately it’s like I have to enact Orthodox, nonmystical traditions to get mystical bread. But I get weary of plastic shamanism and these Neo-Gnostics. I’m interested in reality, and I think even the bounds of science become misty when you’re really diving deep into the reasons for why certain things happen. And I love the idea that we can hinge on something like the molecular makeup of fog, because it’s not of our built environment. For things to be illuminated, they should remain in the mist.

RS So how do you define mysticism?

HGH Ecology. The complex unseen relationships of organisms and their nuances and paradoxes, relating to the linguistic traditions of humanity.

RS Is that another way of saying ‘union with God’?

HGH Yeah, if God is all the manifested language of all time of all humans trying to have reverence for something that’s greater than us; that’s before, after and during us, then yes. But not if God is, like, a person.

RS How do your art objects relate to your faith?

HGH I work every single day on an interspersed practice of devotional prayer that I hope to try to, like, illuminate things to myself into personally. And then I try to materialise those devotional moments into objects that I hope to charge with some type of metaphysics, that may be the linguistic quandary that I used to get to that object. And then I hope to do work in the real world with Fall River MOCA, running this nonprofit museum where the ministry relates beyond just the optics or the icon or the venerated icon, if that makes sense. I really love making objects. They’re therapeutic for me. They’re part of the holistic function. But to me, the whole work is part of a process of devotion and metaphysics that relates to the linguistic tradition.

RS So would you say that the objects collectively create a kind of unified philosophy?

HGH It’s a snail trail. Or a map of detritus. I think the works are independent icons of multicultural and multinational belief structures, if that makes sense. And they’re not afraid to be spiritually, culturally appropriative, if that makes sense. I mean, when I was near eighteen years old, I was playing in a hardcore straight edge band, touring with this band and passing out copies of the Bhagavad Gita, you know? Art is my own in the Blakean way. And it’s the world that I’ve built to navigate my own shortcomings, my benefit, the benefactors of growth, the detriment of change of life and all that stuff.

And ultimately all of the things that I really thought I was beating over people’s heads didn’t stick nearly as much as I wanted it to. And the things that did stick were surprising to me. And they’re still surprising: the messages that I get regularly from people. Somebody DMs me on Instagram, talking about my work, saying that the way that I dealt with the passing of my mother helped them in a way that they weren’t expecting. So it’s like, this venerated icon that I’m trying to imbue with this aspect of transubstantiation, or filling it with spirit, has gone off and lived in the world through the sublimation of media.

What I think about is, Ken Kesey said that shit floats, cream rises. There’s always going to be shit that floats to the top, but after all the cream rises, and that’s the thought process of this loose mystical cosmology.

RS Have you found that the artworld is fairly receptive to your spirituality?

HGH Uh, well, I feel the artworld buried my mother, which is a really weird and beautiful economic happenstance that I’ll forever feel indebted to. She’s in a cardboard box upstairs in my room, you know, cremated. So it’s like, I publicly went through the loss of my matriarch. And humiliatingly, I didn’t have the capital to bury her. And I was on Instagram and made a post about needing some financial support for this loss. And it wasn’t five accounts giving me $500. It was $5, $12, $6, $2 from strangers from the artworld that knew of my work and the representation of myself through media, supporting some aspect of me as a personal individual to deal with this universal reality that everybody’s going to have to deal with. I know there are a lot of people who can’t stand this type of work. That’s fine. It’s not for them, but there are some people who really just connect with it. And the artworld has provided me a lot of space, respect and care based on the labour that I’ve put in to get to this point.

RS Your work all revolves around architecture, in some way or another. Does that seem right to you?

HGH I think it all came from the fact that I, as an autodidact, had a lot of different practices and jobs. I worked as a welder metal fabricator, bronze patina finisher, a carpenter woodworker. It all really helped me understand what was behind the walls. I had to go fix plaster sheet, rock walls, and I learned that a wall is like a series of little pieces. And then individuals took trowels of plaster and globbed it on. What we see is a smooth finish, but what’s behind here is a mess of hair from horses and tree from woods. And sometimes even wool from sheep from the 1800s. So I was looking at living architecture, vernacular histories, manifested in jerry-rigs and odd jobs and weird layers. I saw the same proletarian faith or linguistic faith or reality that I came from referenced in the built environment. And I was astonished by it. And I started reading – what did first-period architecture in America look like? When did it transition from the colonial to Carpenter Gothic to the Victorian period to Mies van der Rohe? How do these forms influence our lives? So it’s similar to my attempt to deconstruct and reconstruct the spiritual world.

RS Earlier you said art was therapeutic for you. How so?

HGH Catharsis is the ultimate holistic function for art. And I must make art at all times. I’m a very anxious person. I have an intuition that’s very, very strong and it manifests in physical and nonphysical ways in my body that have been really hard to reconcile. It’s as if I had visions enacted onto me, but ultimately know that I’m within my corporal being within my body, if that makes sense. I have out-of-body tremors. I lose language at points. I spend eight hours a day in the bath, submersed in water, continuously drawing baths. So today from three till about eleven, I was in the bath. I’ve suffered in the past from ulcerative colitis, stomach ulcers, panic attacks, hospitalisations, whatever. Ultimately, I know it’s just artefacts of a complex lived reality with potentially some PTSD.

RS From specific events?

HGH When I was younger, I was robbed at gunpoint, beat up with a metal baseball bat. So that tends to leave me in a state of hypervigilance. But the bath is redemptive in the sense that it feels as if I cannot attempt to reenter some type of womb. So the objects that I make, that people see in these refined exhibitions, those are for the time that I’m not in the bath, and the art that people see with FRMoCA, that’s really the time that I’m not able to be in the studio.

RS What are you doing in the bath? Reading?

HGH Constantly. I’m just like, St. Augustine of Hippo was in a gang – I gotta research this! And I’ll spend hours reading about it.

RS I’m always relieved to know that the saints and mystics didn’t all lead saintly lives. That knowledge would have given me solace as a kid.

HGH Yeah, I was a fucking terror as a kid. I dropped out of high school when I was sixteen or seventeen years old. Leading up to that, I did not graduate a single year. I didn’t graduate from anything. I was in special education my whole life with people who were like severely mentally handicapped and with ESL students, my first language is English.

RS Why was that?

HGH I just didn’t really understand how language could serve to better me. I just like didn’t know why the hell I was in there. Like I’m skipping school every day. Getting suspended, telling the principal go fuck yourself. And art has really been the only thing ever throughout time where I felt the most understood. It’s funny because now, so much of my art is writing and linguistic morphism and words. But they’re like oriented in this symmetrical madness that is therapeutic for the dyslexic in me. It’s easier for me to see the space between the words than it is for me to see the words on the page.

RS How has Fall River affected you?

HGH Yeah, I was born half a mile up the street from where I live now. And when I was born all four generations were there in the hospital room. Harry Gould Harvey the first, second, third, and me. My family has been in Rhode Island since the 1650s. Originally, they were Quaker settlers in Narragansett Bay. I’m one of the first born in Massachusetts. And it’s that relationship to the place that made me so magnetically drawn to this place. I know everybody from the gangsters to the mayor, and I have no problems, versus going into some major city where I don’t know nobody at all, and never could, and act as if I belong there. Also there is a vernacular etymology to this region that means it becomes linguistically and ideologically schizophrenic for me to be elsewhere, because it’s so antithetical to the linguistic cloth my family has been cut from.

RS What’s an example of this speech?

HGH An example would be, uh, you know, like, I mean, uh, you know, it’s like, I’m driving and my fucking steering wheel starts falling apart in my hands and standing, so I said to the guy and I said, what the fuck am I supposed to do here? The steering wheel was falling apart. I got a 67 Camaro. Fucking steering wheel never fell apart. So I go to fall river for fucking douche bags. They tell me there’s nothing he could do for it. I’m like, what do you mean you could not? So I tell them, let’s try to get this fixed up so I don’t have to fucking come in and cause any problems, you know what I’m saying?

RS I see.

HGH There’s no internal dialogue. It’s all outward. It’s a very different linguistic reality, where all words are visible. So you have to kind of exist in poetics.

Ross Simonini is a writer, artist, musician and dialogist. He is the host of ArtReview’s podcast Subject, Object, Verb