The muddled practice of nostalgic self-referentiality in films about film drives much of mainstream movie production today

Damien Chazelle’s Babylon (2022), a cacophonous depiction of 1920s silent-era Hollywood, ends with a montage dedicated to cinema. Film scenes flash by, from the Lumière brothers’ The Arrival of a Train in 1896 over to Dorothy in Oz, past the mournful eyes of Renée Jeanne Falconetti and Anna Karina, then to Ingmar Bergman and Stanley Kubrick, until eventually arriving, of course, at Avatar: The Way of the Water (2022). This is film history, Chazelle seems to say. This is the culmination of cinema, boxed in and canonised, consumable in under two minutes.

If Chazelle hoped for this to be admired as an ultimate display of love for the medium, he was misguided. Not only is his attempt cloying and reductive, but the concept of ‘a love letter to cinema’ has become so ubiquitous in film marketing and criticism that it has become a joke. A cursory search on Twitter reveals some earnest admiration, but mostly memes and quips from users bored by the recent oversaturation of film releases adhering to this micro-genre. Some critics have even taken to teasingly trademarking ‘The Power of Cinema’ to recognise how it has been commandeered as a commercial product, born in the minds of audiences and sold back to them. The muddled practice of nostalgic self-referentiality in these films about film drives much of mainstream movie production today; filmmakers have a tendency to look inward for their stories, but so does the industry as a whole.

It’s important for the Hollywood machine that this reflexive mode exists: to sustain the mythology of the film industry as a place where starry-eyed wannabes can make it big, and to remind dwindling cinema audiences of whatever magic the industry might deliver. Cinema admissions in the UK, for example, are tentatively returning to pre-pandemic numbers but there is still a way to go. And how do you convince a growing majority who prefer watching their own small screen to the big one? Maybe you only reboot franchises like Ghostbusters or Scream, or make sequels and prequels to older films that familiar audiences will care about seeing return to a big screen, à la Top Gun: Maverick (2022; and this year nominated for a best picture Oscar). The method is simple: exploit viewer nostalgia and uphold Cinema’s golden past. A more complex approach to the self-referential mode is the prevalence of films that don’t rely on existing IP, and instead centre the moviegoing experience as the narrative. In rendering the very act of cinema attendance as, well, cinematic, these films create a new lure to the theatre. It’s an approach that feels as patronising and self-congratulatory as the reboots do; here is Hollywood’s glory and you, for a price, can be a part of it too.

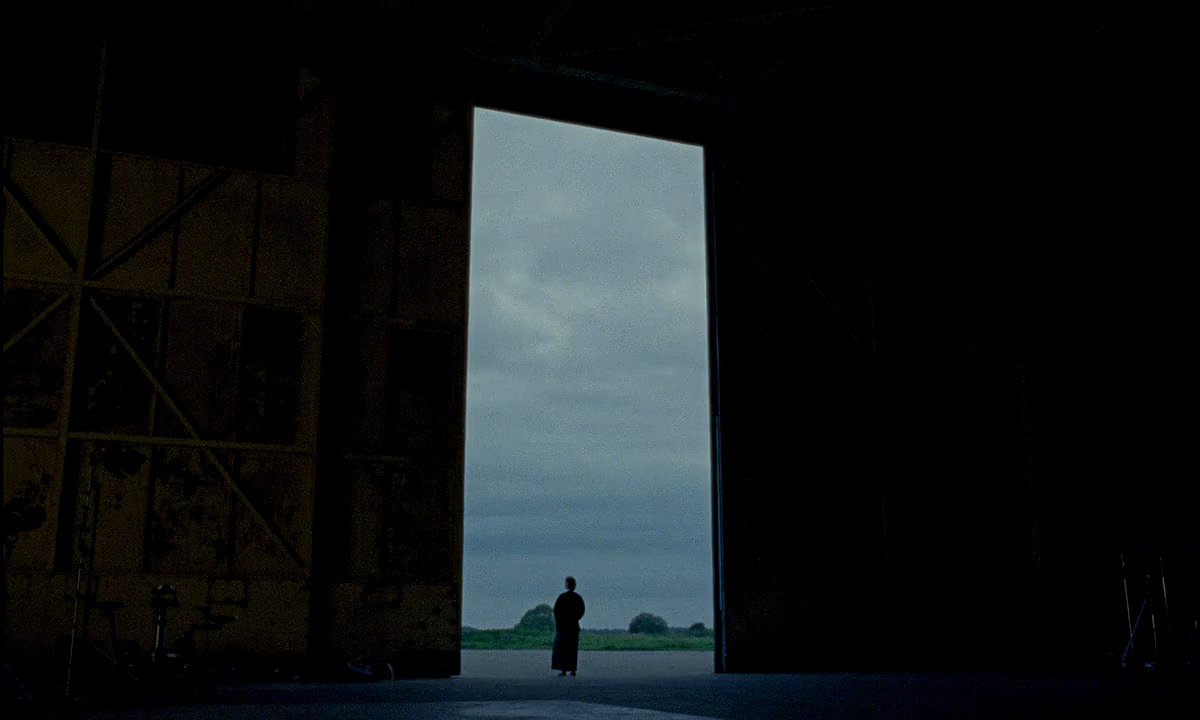

Recent films that use the cinema as a space for revelation – like Sam Mendes’s Empire of Light (2022), in which a romance develops between two struggling cinema workers – and films that use cinema history as the basis for their narrative – like Babylon – entertain an idea that moviegoing itself has a gravitas worth celebrating. As a film critic, I too believe that to be true. This ethos, or at least the idea that it’s worth paying to see certain films on a big screen, is arguably what powers the Hollywood reboot-machine. It is of course often preferable to see films on the largest screen possible, irrespective of genre, but promoting the phenomenal or aesthetic experience of moviegoing can also be coopted as a contrived scheme for better box office figures which would, in turn, offer a kind of proof that the system is working. And what do all of these films really achieve in their various attempts to amplify the cinematic experience, when they restrict it to a wistful or sensationalist history – and play into the corporate hands of studios who reproduce and capitalise this twisted mythology ad infinitum? Absent from the recent Oscar nominations is Maria Schrader’s by-the-numbers Harvey Weinstein scandal biopic She Said (2022), which was perhaps too self-referential for the industry.

While Babylon attempts to depict a far uglier side to Hollywood’s history, the film’s provocative style and visual excess undeniably perpetuates a kind of dazzling reverence. Set in the supposedly debauched culture of silent filmmaking, it follows matinee idol Jack Conrad (Brad Pitt), boisterous new starlet Nellie LaRoy (Margot Robbie) and ambitious outsider Manny Torres (Diego Calva) through the tribulations of making it in movie land. Its ‘love letter’ aspect not only occurs through the montage but also in Chazelle’s critical, and embarrassing, mistake: by orienting part of the film’s finale around a tacky homage to one particular, far better film. After over three hours of belligerent spectacle, the filmmaker overtly aligns the narrative with that of Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly’s 1952 masterpiece Singin’ in the Rain, which too is a homage to the era in which silent filmmaking shifted to sound. Yet where Singin’ in the Rain was expressive and effortless in both its nods to history and its cinematic achievement, Babylon feels burdened by trying to be cinema, of hoarding references and relics instead of doing something new.

In filmmaking, the line between derivation and homage is often thin. Layered references to other works, an acknowledgement of the history and talent that has come before, are not, by definition, a bad thing. Many great filmmakers are great film historians and their films are better for it. Jordan Peele’s Nope (2022), as a recent example, takes several elements of film history – the work of early motion photographer Eadweard Muybridge, theories of spectacle, and the longstanding exclusion of Black filmmakers and actors in contemporary discussions of canons and legacy – and uses them to create something blisteringly original and insightful. What Peele doesn’t do is let history or indulgence plaster over poor storytelling. If film history can be seen as living and ever-evolving, as something worth experimenting with and developing upon, then Nope offers far more towards it.

Equally prevalent of late is the filmmaker-Künstlerroman, as seen in Steven Spielberg’s Oscar-nominated The Fabelmans (2022) or Joanna Hogg’s two-parter The Souvenir (2019 and 2021), and seems to share much with the autofiction boom in contemporary literature. These films also have a certain navel-gazing quality to them, but the craft of filmmaking retains a sincerity that the capitalist enterprise of Hollywood has, of course, not. As such, the films gesture towards a more intimate, expressive portraiture. Spielberg’s latest sees the filmmaker – one who is inextricably tied to the culture of movie nostalgia – skewer his own love for filmmaking and the consequences of such a devotion by aligning it with the history of his parents’ marital breakdown. It makes for a far more compelling and honest story, even if Universal Pictures’s marketing campaign would rather suck you in with its inevitable ‘power of cinema’ tropes alone. Spielberg’s film is still a mark of the ubiquity of the nostalgic mode, but his critique of this is evident. Even if Babylon, or another recent industry-focused film like Andrew Dominik’s egregious Marilyn Monroe drama Blonde (2022), can be read as condemnations, they never question Hollywood’s foundational mythologies – of glamour and grime, starlets and underdogs, scandals and downfalls.

The hope that cinema of this kind could reinvent itself, could look forwards instead of backwards, could try out some new ideas, is often proven naive. The incentive to make these reflexive films about film has likely been heightened by the pandemic years, with filmmakers perhaps having taking stock of their careers or their cinematic inspirations in a moment of crisis and shutdown. Declines in cinema-going have played their part; my screening of The Fabelmans began with a short video from Spielberg thanking the audience for seeing the film in a theatre. But, even if audiences flock to cinemas for the latest instalment of a beloved franchise or a salacious biopic once a year, it might prove an unsustainable model. That studios would rather exhaust themselves convincing us of cinema’s greatness than foster that exact feeling organically through varied, challenging filmmaking is a farce. Hollywood’s hollow nostalgia and narrow focus on high-budget, self-interested material will surely ensure rising production costs as studios attempt to out-spectacle one another. Ticket prices will only grow as a result. While those behind these ‘love letters to cinema’ may want you to believe they care about cinema and want to see it ‘saved’, the future they suggest is unambitious, recycled and lazy. Hollywood will continue to reward this through top prize nominations for films like Top Gun: Maverick. As a gesture of thanks to cinema’s lone saviour, Tom Cruise, perhaps it’s only fair.