From 1960: Lawrence Alloway begs fans to look beyond the violence

For a decade Robert Melville’s criticism of Francis Bacon has set the tone and the direction for a reading of Bacon’s paintings. In 1949 he nominated him as the hottest thing since Un Chien Andalou and relished, in one of the paintings, “the fact that the curtain is sucking away the substance of the head” (an anticipation of Melville’s description of the sky-licking activity of Butler’s Watchers). In 1951 he compared A Fragment of a Crucifixion by Bacon to “those perverted animals in The Temptation of St. Anthony’’ (which Melville used to meditate on, faun-wise, in the 1940s). Bacon left “a rich taste of mortality in the mouth” of Melville. The flesh that Bacon painted was “obscenely immortal in renewal” whatever that means, but the steaming morbidity is unmistakeable. Melville describes Bacon, too, as the painter of “a privacy that is quite illusory”. Melville’s 1959 piece on Bacon (reprinted in the Marlborough catalogue) goes on in the same way. “Bacon might be said to have covered the lampshades of his immediate predecessors with human skin” and “he discovers in the act of painting the felicities of the death warrant”. The bibliography in the Marlborough catalogue leaves out all items about Bacon except those by Melville and David Sylvester (and this is not complete even). Not only does this mean that the best-ever article on Bacon, by Sam Hunter, is omitted, it means there is no opposition recorded to Melville’s creepy reading. Sylvester, though in a position to do so, never got around to writing about a Bacon who was not a bogey-man. “The smearing means destruction: the face is wounded, shattered” and “privacy invaded”, to quote Sylvester’s latest words on Bacon, are variants of the Melvillean canon.

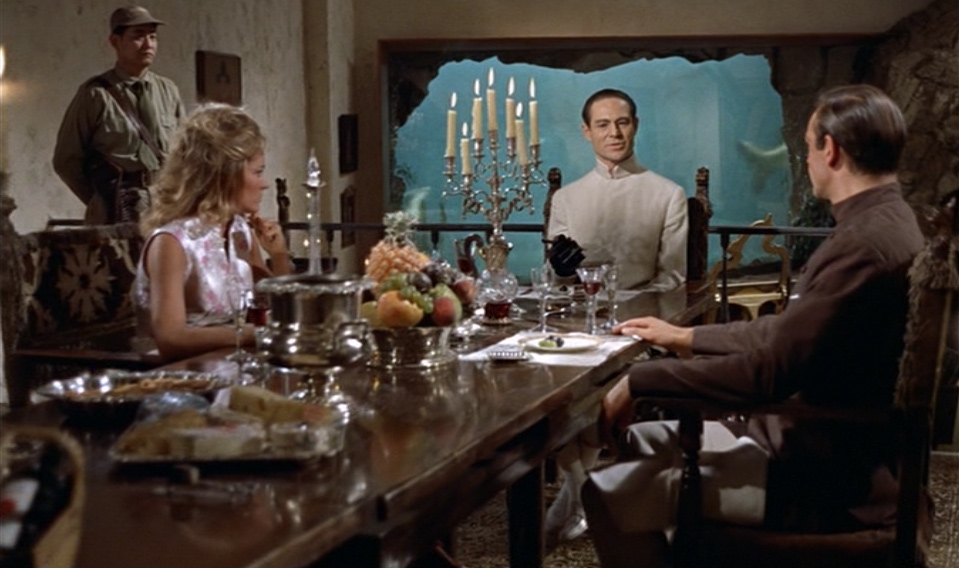

Melville’s criticism of Bacon is like the conversation of Dr. No, Ian Fleming’s fairly sophisticated descendant of Dr. Fu Manchu. At dinner, with James Bond, his guest and victim, the arch-criminal discourses in ornate and shapely sentences on pain and endurance. He is dedicated to a kind of inverted ergonomics, the point of which is how much agony and humiliation a man can take. The luxurious table, the fastidious and sadistic recital of torments, is strictly the world of Melville’s art criticism. So steeped is Melville in all this sinister stuff that he cannot even say straight that he thinks Bacon is influential; no, Bacon must be “satanically influential”. (In fact, he is hardly influential at all now, except in Milan.) In terms of dull old art history Melville has less to say: in his earlier articles he described the spatial ambiguities of Bacon’s pictures as a baroque version of cubist form. Now he suggests Bacon’s image is a going beyond tachism. It seems clear from these compressed and perfunctory enigmas that this is not where Melville’s interest lies. He is concerned with Bacon as a muscle-man who puts into visual form the tortures Dr. No, the Brain, conceives. The question, “Is Robert Melville Francis Bacon?” can, perhaps, begin to be answered in the negative. I don’t want to suggest Bacon is really Sunny Jim: on the other hand, it would be a change to see Bacon in his own oddity, rather than in Melville’s.

Much of Bacon’s imagery, with or without Melville, is beginning to look corny now. It was nourished on the popular existentialism of the 1940s to which the American novel, surrealist values, and the experiences of World War II, contributed. As Stephen Spender observed in 1953: “His vision seems to start off with a complete acceptance of concentration camps”. A Sartre-type spectrum of feeling from disquiet through paradox to atrocity characterised much of the 40s. In Melville’s hands this complex acquires overtones of diabolism and wickedness (like Eartha Kitt’s “I want to be evil”). Comment on Bacon’s popular sources (screaming woman from The Battleship Potemkin, tyrants haranguing) tends to stress the violence of the material at the expense of another function. It needs to be related to Bacon’s use of Velasquez’s Pope Innocent X and Van Gogh’s The Painter on the Road to Tarascon. To Melville, Bacon’s paraphrase of the Velasquez is “a peculiarly exhilarating image of moral collapse”. (People get their kicks in different ways, I suppose: some people at a football match, others at moral collapse.) Another recorded but probable stimulus to Bacon’s men and curtains pictures is a portrait, attributed to Titian of Cardinal Filippo Archinto (Johnson Collection, Philadelphia) in which a transparent curtain hangs in front of the seated Cardinal, leaving only part of an eye and his ear clearly in view. Bacon’s references to popular and fine art can be related also to his reliance on the format and tonality of Grand Manner painting, and his technique is, in some respects, an abbreviated version of “Venetian” painterliness. Bacon has a built-in taste for the slice-of-art similar to Sickert’s “echoes” in which he took off-beat images and pulled them into easel painting leaving their origins awkwardly, frankly visible. This play of conventions, a Malrauxesque intrigue between artists, seems as useful a way into this aspect of Bacon as through Melville’s dining-room over the torture chamber.

Motion is another fundamental concern of Bacon’s and it has not yet been examined much beyond stock references to Muybridge. Some Bacon pictures seem planned as successive episodes in one action. But apart from the comic strip or flip book implication it is the motion effects within single canvases that are interesting. In early Bacon, motion was blurring and transparency, constantly fraying, volumes dissolving. Seated Figure (undated in the Marlborough catalogue, but I have seen it around for years) shows this approach. The trembling mobility of the figures (linking to Giacometti, something which Sylvester could have discussed and was expected to do) retained a basically intact human proportion. Bits might be missing or transparent but the distribution was as we know it, as far as it went. In the new paintings, however developing out of the Studies of William Blake’s Life-Mask, the body, though solid and continuous, is often crumpled and folded. Centripetal rather than successive forms result from movement. This can be seen in the new heads which are not the best paintings in the show but the best Bacon has done lately. Here his creaking melodrama seems to work in a more intimate relation to painting problems than it has for years. The interplay of living flesh and meat, the suggestion of a skull under the flesh, which also looks like an X-ray photograph of a painted head by Honoré Daumier, shows Bacon combining his two gifts of painter and image-maker. When these separate it has usually been the painting that suffers; as the paint drains away a provocative but gaunt image is left in the bath. Bacon’s problem in the unification of his gifts is to keep his paint rich, so that we are not left with the bare spectacle of his fast-dating Grand Guignol and the muscle eroticism of his nudes. In the Van Gogh series the paint got out of control as it flooded the surface which previously it had only grazed, like an outburst from a gipsy violin after messages in morse code. In the portraits however, the complex, provocative imagery and the deposit of paint are united. And when this happens one needs less a Melvillean refinement than a capacity to experience a form in motion as it becomes an image in time. Time is both the running together of features as the model moves and the skull which the twisting planes of the head conjure up. To recognise this paradox of time as living motion and time as death is not, I hope, to join Dr. No’s dinner-table talk.

Originally published in Art News and Review, 9 April 1960