The fifth Dragon Hill X ArtReview Writers Residency considers the purposes of the artist (and art writer) residency and what role it plays in artworld advancement

“So you’re just going to reside in a house somewhere in France?” was the unimpressed response I got when I shared the news of my residency with a friend who neither knew nor cared much about the art industry. As I tried to explain to her what an art residency (in my case, an art writer’s residency) is and why it’s a big deal, it suddenly occurred to me that the purposes and significance of residencies were not as self-evident as I’d thought. Residency programmes are everywhere to be seen in the world of contemporary art. Almost habitually, artists, curators and art professionals are on the lookout for sought-after residency opportunities. We are convinced that residencies are valuable career boosters, often without asking why they matter for us, or what roles they play in the artworld. As I embarked on my first writer-in-residence experience at Dragon Hill, I decided my project was to ask questions about the function and meaning of residencies.

Although location, scale, expected outcome and structure may vary for different residency programmes, most of them offer residents space and a stipend to focus on their practice and research for set periods of time. For many creatives, residencies serve the need to be free from everyday concerns and social restraints. But why do we have to get away in order to create? What does it say about art and its relation to life, if we believe the best place for creativity is an unperturbed oasis, detached from the troubles of reality? At Dragon Hill, where my fellow residents and I didn’t need to worry about getting groceries, cleaning the house or paying utility bills, I started wondering if artworks made in a studio shielded from daily drudgery and prosaic worries lose touch with real life more easily. Creativity benefits from the working conditions provided by residency programmes, but making art or writing in residency havens – secluded and serviced to different degrees – also seems to change the connection between living and creating.

Residencies help artists and curators cover the cost of creating and living, especially when they are at the stage where their artistic practices are financially dependent on taking on extra work. However, precisely because of this, in places where waning public arts funding causes the level of uncertainty faced by local creatives to spike, such as the UK, residency programmes can feel like a problematic substitute for less precarious and more systematic forms of support for the creative community. As ACE grants, permanent contracts and long-term institution collaborations are virtually impossible to get hold of for most artists and curators, hopping from one short-term residency to another becomes the only way to secure funding and presentation opportunities for their practice and research.

What further complicates the issue is that participation in residency programmes usually requires flexibility that is a luxury for many to afford. Am I able to take four weeks off from my part-time jobs? Should I sublet my ridiculously expensive flat and studio in London? Will I miss opportunities for better gigs while I’m away? It almost becomes a vicious circle, where professional certainty and financial security are never an option. Yet, as content like open calls and meet-our-resident posts fill our Instagram feeds, residency programmes contribute to maintaining the illusion that the artworld is buzzing with opportunities and resources for everyone. Swept under the carpet is the need for sufficient funding and effective infrastructure, as well as questions like what the reliance on such a casualised means of support as residencies implies for a creative career.

At the same time, when it comes to survival in the art industry, residency opportunities mean more than just the time, space and financial support they provide. The bigger draw is often the exclusive access to certain resources granted to residents and alumni. Participating in a high-profile programme allows an artist or a curator to gain, for example, professional connections, press attention and institutional credentials. All of these rewards are indispensable factors for a successful career in the arts, so much so that they can outweigh other purposes of undertaking residencies. With an active role in the artworld’s validation mechanism, residency programmes are also easily stranded in the networked echo chamber of museums and galleries. It’s not unusual for the names of a prominent residency programme’s alumni to be found across various institutions, biennales, art fairs and news about art prizes over a period of time. Although the relative flexibility and independence of residency programmes create space for experimenting with new modes of career development and support alternative practices, many of them are compliant with the institutionalised and commercialised artworld, where ‘to those who hath, more shall be given’ still holds true.

During my residency, I strolled in nearby villages aimlessly every afternoon, never able to tell if I was anything more than a tourist. Can any in-residence creative be more than a tourist? Many residency programmes today pivot around the commanding themes of cross-cultural conversations, community engagement and participatory research. However, the usual lengths of residencies, ranging from several weeks to half a year, mean that residents have limited time to forge connections with their sociocultural surroundings. Yes, artists and curators report that they’ve built meaningful, enduring bonds with local communities during their residencies and have been inspired to reimagine their practice, but we also all know that a poorly contextualised and self-absorbed exhibition produced at the end of a three-month residency isn’t too rare to come across. Partnerships between international residency programmes located in major Western cities and funding bodies with specific geographical or cultural foci increasingly introduce art practitioners from all over the globe to the capitals of contemporary art. Guided by the vision of diversifying the West-centric artworld, these partnerships create invaluable opportunities for crossing borders and spotlighting overlooked practices. However, without careful definition and constant reflection, this vision runs the risk of evolving into a streamlined yet uncritical process of pumping newly ‘discovered’ non-Western artists and curators into Western metropolises’ exhausted artworld. One wonders how many residency programmes are equipped – conceptually and operationally – to foster dialogues that truly decentre the global art scene, and how many just assume that hosting someone from country A for a few weeks in country B will automatically generate in-depth exchanges.

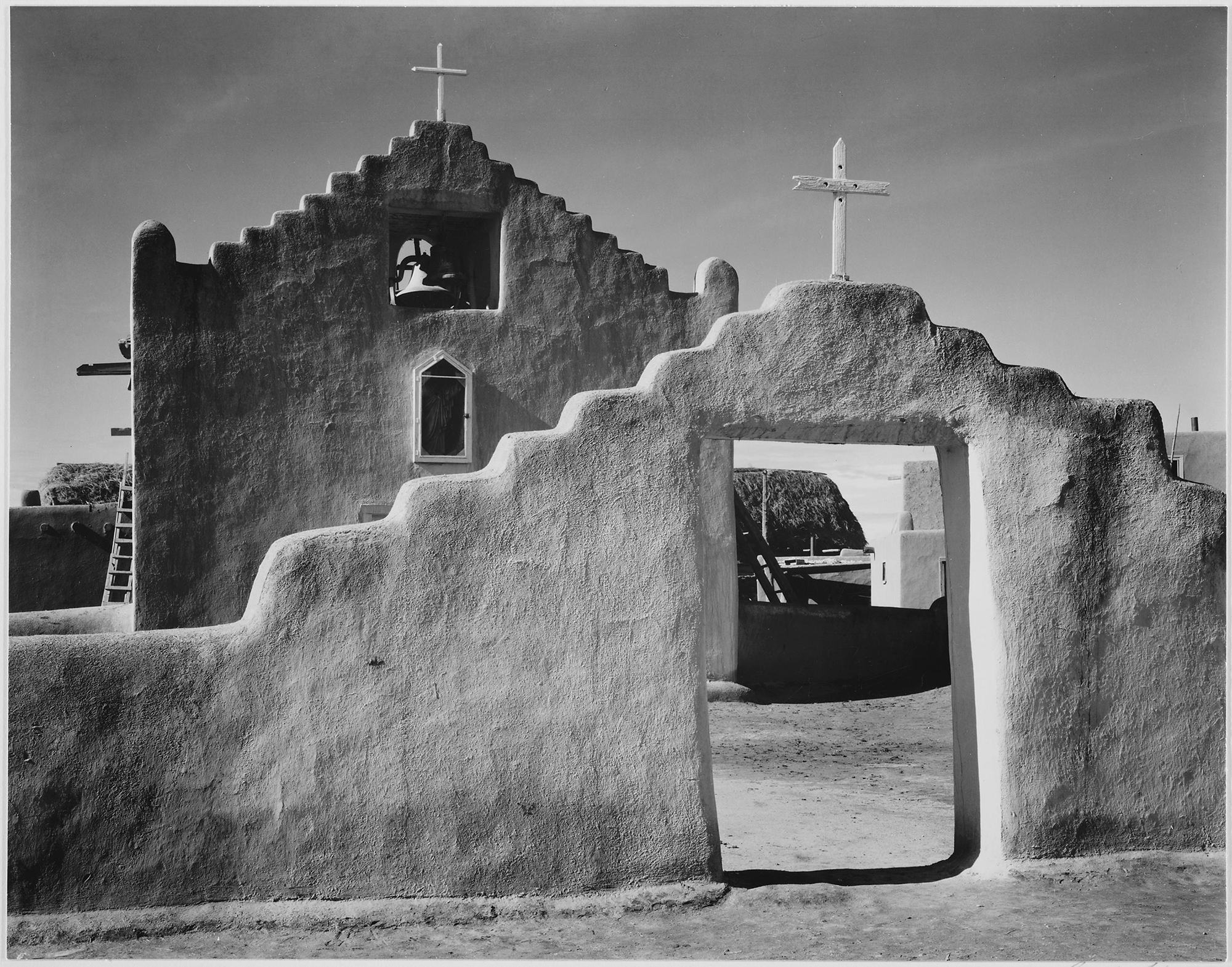

At Dragon Hill, I realised a residency was capable of creating moments when distance was allowed between my mind and the world around me. One thing that has grown out from this rare distance is the questions I’m asking about residencies in this article, questions I haven’t thought about until a residency gave me space and time to do so. In Rachel Cusk’s novel Second Place (2021), a tribute to art philanthropist Mabel Dodge Luhan’s 1932 memoir about the Taos art colony in New Mexico, the narrator explains that a sojourn in a marshland cottage is ‘where artists often seem to find the will or the energy or just the opportunity to work’. For many people who are forging paths for themselves in today’s artworld, residencies hold the weight of more complex needs, desires, hopes and precarities. We start dreaming about becoming something-in-residence while still in art schools, churn out one after another application as we scrape by and believe that flying off to a renowned residency means we’ve finally made it. Providing basic resources for the survival of creative and critical practices, residencies are also entangled in the multifaceted game of cultivating connections, accumulating credits and climbing the career ladder in the artworld. How do we engage with the complexities of residencies, and how do we shape them, so they spark and sustain the drive to make art, write about art and ask questions about art?

Cindy Ziyun Huang is a writer based in London