The second Dragon Hill X ArtReview Writers Residency text discusses abstraction in the context of work by Anthony Akinbola, Patrick Alston and Ludovic Nkoth, the three artists on the Dragon Hill residency with the author

Over the course of 2024, six art and culture writers selected by ArtReview have been joining groups of visual artists selected by London’s Unit gallery on a residency at Dragon Hill in Mougins, near Nice. This historic home, designed and built in 1964 by Jacques Couëlle, is set in a private domain that has counted Pablo Picasso, Jean Cocteau, Yves Klein, Yves Saint Laurent and Leo Castelli among its residents. Some of the writers on this residency have written previously for ArtReview, others have not; some of the artists are represented by Unit, others not.

The second resident, London-based writer Tom Denman, lived at Dragon Hill in June and early July. He has written a text on abstract painting by Black artists, focusing on the work of Patrick Alston, Anthony Akinbola and Ludovic Nkoth, the three artists on the Dragon Hill residency during his time there.

We’re in a garden overlooking the hills of Mouans-Sartoux, about ten kilometres north of Cannes – abstracted, as it were, from the ‘real world’ – and we’re talking about abstraction. The key concern of the conversation, raised by the three artists I’m sharing this residency with, is the institutional and market demand on Black artists in the US to enact legibly Black tropes, with gatekeepers hellbent on promoting the racial content of artworks, often disingenuously, above all else. Anthony Akinbola, for instance, cracks up at the assumption that the title of his fabric work Jubilee (2021) intentionally refers to the Emancipation Proclamation – an assumption made by the online voice description attending its inclusion in By Way Of: Material and Motion in the Guggenheim Collection, at the Guggenheim in New York. Yes, it’s funny, as things are when authority is so off the mark, but there is something worryingly reductive about overriding the very subjectivity that inclusivity is meant to bring.

As a white critic (and in this context, even though I’m also Japanese, my responsibility as a white person comes to the fore), I feel implicated. I think about whether, when I’m seeking out the ‘critique’ in art, I’m not forcing it to assimilate to my idea of what makes it good. If abstraction – as Ad Reinhardt argued during the 1940s – puts the viewer inclined to interpretation in the position of creator, perhaps it’s incumbent on the critic not to prevail on an artwork to fill a certain political bracket. And so I set myself the task of considering how the three artists here – Akinbola, Patrick Alston and Ludovic Nkoth – have utilised abstraction to joust with hegemonic pressure to be Black on a white viewer’s terms.

Through abstraction, Alston makes his presence felt without opening it up to racial categorisation; the liberation associated with gestural forms gains undeclared political meaning. During the residency, Alston has been working mainly on two paintings, one predominantly red, the other yellow: naïf, slowly churning suspensions of crosshatched, whirling marks that decelerate the fleetingness of preverbal emotion; the preverbal as prepolitical, or pretraumatic, which is not to say that Alston’s practice is one of pseudo-utopian escape. Rather than shy away from reality, his layering and blending of marks seem to carry out the palimpsestic, perpetual (because it’s perpetually thwarted) practice of sustaining a prelapsarian world. Before coming here, I wondered if my Edenic surroundings wouldn’t desensitise me to the harshness of life, but maintaining such indifference would be like meditating indefinitely without a single intrusive thought. It seems to me that the labour in Alston’s work – which is often evocative of a beautiful garden, his work on the Jenkins Johnson Gallery stand at Art Basel this year, Remember the Lilies (2024), even referencing Monet – is up against an equally inevitable rupture of innocence.

Events occurring on a not-so-distant shore prompt me to read an excerpt from the Palestinian theorist Edward Said’s Reflections on Exile (1984), in which he introduces the term ‘contrapuntal’ to define an awareness of existing in ‘simultaneous dimensions’. I think something similar to counterpoint is at play in the work of the artists I’m conversing with. I’ve been talking to Akinbola about the road, the subject of his work-in-progress, a body of works – possibly paintings, though the project is still in embryo – abstracting the phenomenology of driving. The artist’s commitment to the road’s marks and materiality poses a conceptual challenge, for me at least, not to veer into signification (of a Black man driving in the US). Is it possible for the works to be just about the road, and not just about the road, at once, with the work’s point of conflict being the gravitational tug between the two dimensions? I think about some of Akinbola’s developed work along similar lines. Much of it starts off with the politically charged material of the durag, which he then stretches across frames in crisscrossing striations or Sean Scully-like stripes. In these works – three of which he has made here – he tests the extent to which an emblem of American Blackness can be only form.

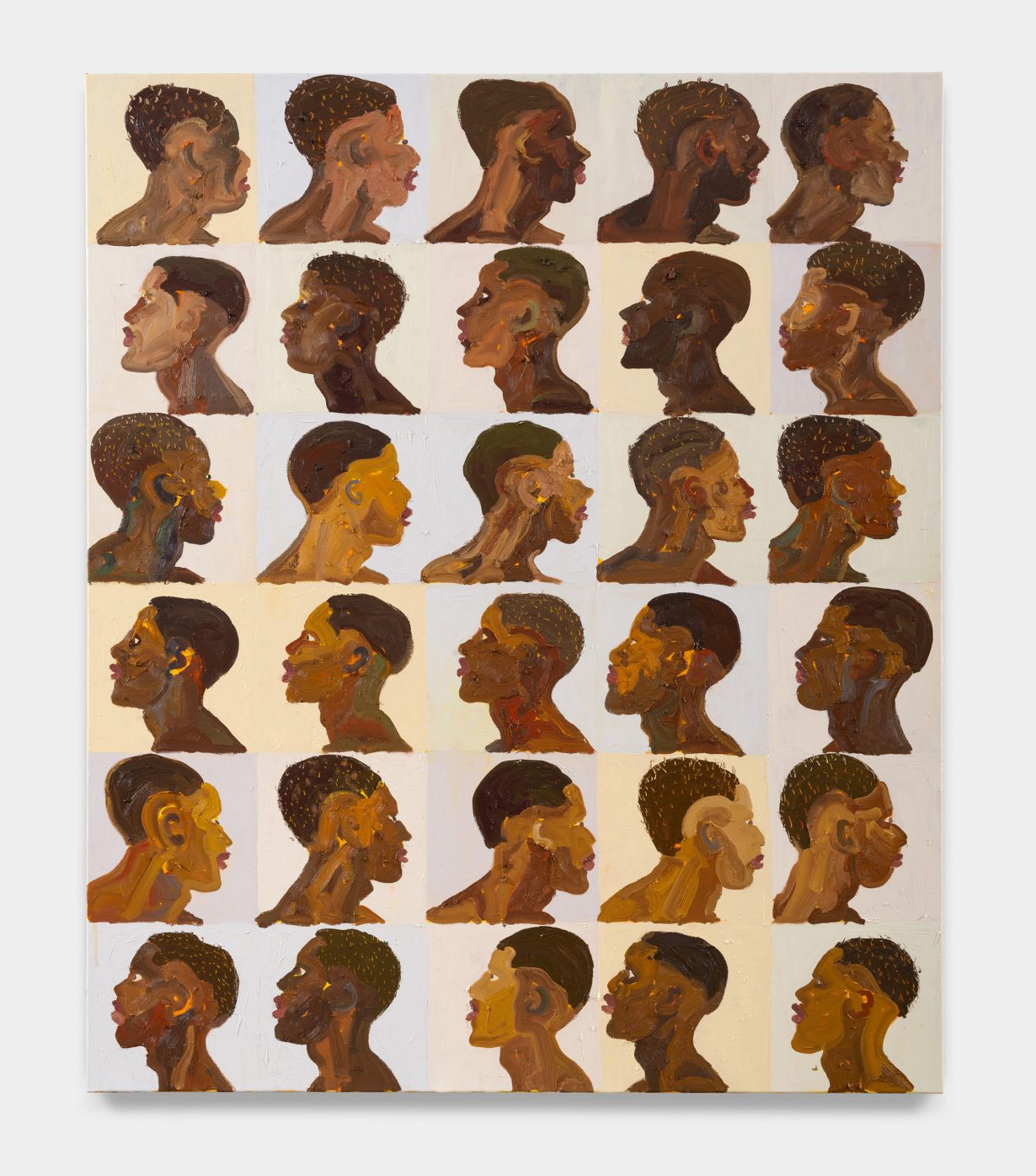

In the local supermarket I keep seeing Moor’s heads: on wine bottles, on the label of a brand of charcuterie. The silhouetted profile appears on the flag of the neighbouring island of Corsica, I discover; I’m wondering whether such heraldry isn’t ancestrally ingrained in racial profiling, whether police mugshots – of Black people – haven’t something of the war trophy about them. In the studio, Nkoth has been continuing his experiment with grids, each square a slightly different dark tone, and occupied by a head in profile. Although Nkoth’s work is technically figurative, his restless, writhing brushstrokes abstract his subjects in real time, and although the mugshot served as an early point of reference for this series, the heads have meandered from this source. There is a point, as I watch him work, when the painting appears complete, yet he crucially oversteps this point, dismantling the grid’s unity as the paint continues to swirl, colours multiply, merge and dissipate, and figures trespass into neighbouring cells. Nkoth’s figures enact the work of slipping away from easy profiling, work that – like Alston’s effort to sustain bliss – is ongoing and unfinished.

Beyond its connotations of systemic oppression, the profile pertains also to criticism: the ‘profile treatment’ implying the encapsulation of a single artist’s output. To a certain degree it is inevitable that language will contain what it seeks to describe. Writing about abstraction, the challenge of respecting its indeterminacy rather than reining it in to suit an agenda – especially when postimperial asymmetries are involved – becomes all the more vital, even if the result is bound to be imperfect. One subtext here is Martinican theorist Édouard Glissant’s call for opacity. More than a matter of being difficult or impossible to decipher, opacity calls on the responsibility of everyone not to reduce people to a code. It’s like when you get on with someone, in paradise or wherever – you don’t need to conceptualise them, or to know everything about them, to do so.

Tom Denman is a writer based in London